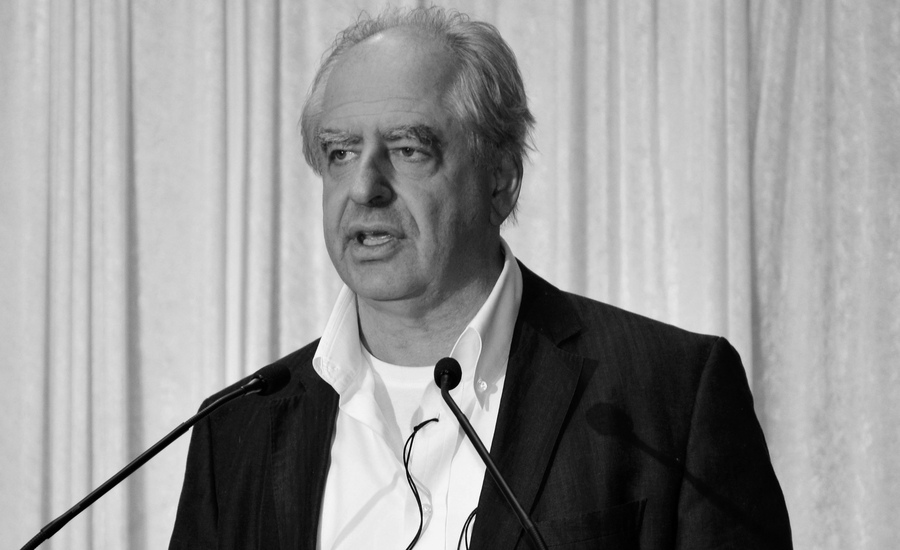

William Kentridge

hasn’t always followed good advice. When he was beginning his career, “all my friends told me to do one thing and do it well,” the artist recalls. “Just do drawing, they said. Just do theater. Only make films because otherwise you get caught between them. For a long time I tried that, and I failed at all of them. Now I don’t even pretend to know what form an idea will ultimately take or what project it will end up in. I just get on with doing things knowing they will end up somewhere.”

This unruly approach has, of late, served him well. Not only has

Kentridge

been the subject of acclaimed solo exhibitions at leading arts institutions across the world, but evocative, gestural and, at times, unsettling work he has also found great favor working within other, more dramatic forms, such as dance, film and theater.

William Kentridge – Still Life, 2007

Using drawing, animation, sculpture, puppetry, tapestry and collaborations with others to produce operas, choreography and other dramatic undertakings,

Kentridge

has engaged with the political history of southern Africa, the early, figurative forays within modernism, as well as wider themes.

However,

Kentridge

did not find success overnight. He failed as both a painter and an actor before developing his winning hybrid of theatrical and figurative forms.

The artist was born on 28 April 1955 in Johannesburg, to Felicia and Sydney Kentridge, a couple of prominent, anti-apartheid lawyers, each of whom harbored a love of the arts. Kentridge’s father defended Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, while his mother was the co-founder of the country’s Legal Resources Center, which continues to offer free legal services for the needy.

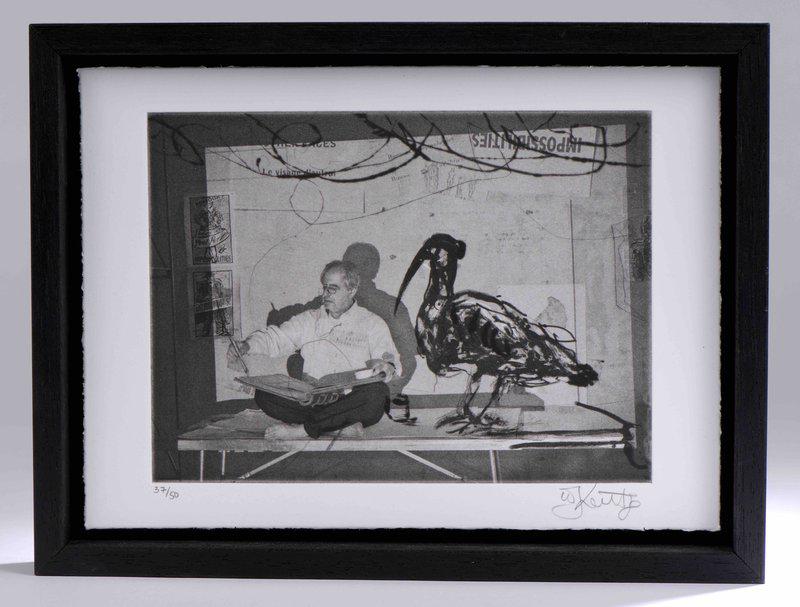

William Kentridge – Scribe with ibis , 2010

William took an undergraduate degree at the University of the Witwatersrand, studying politics and African studies, before taking night classes, then fully enrolling for an art diploma at fellow artist and activist Bill Ainslie’s Johannesburg Art Foundation.

Dismayed by his painting skills,

Kentridge

switched to drama, and studied mime and theater at the École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris. This too proved disappointing. Kentridge later said that after three weeks in the French capital, he knew he wouldn’t make it as an artist.

However, l'Ecole Jacques Lecoq did have a very good directing and drawing programme. “I learned more about drawing from the theater school than I did from the art school,” he later reflected. “If I teach exercises to drawing students or animation students, they’re almost always the theater exercises we did at l'Ecole Jacques Lecoq. It has to do with understanding the energy of a gesture, of what it is to use one’s whole body, of expanding the repertoire of degrees of tension with which one can work, whether one is speaking, moving, or drawing. It’s also a way of expanding from the body outward into finding a meaning in the work.”

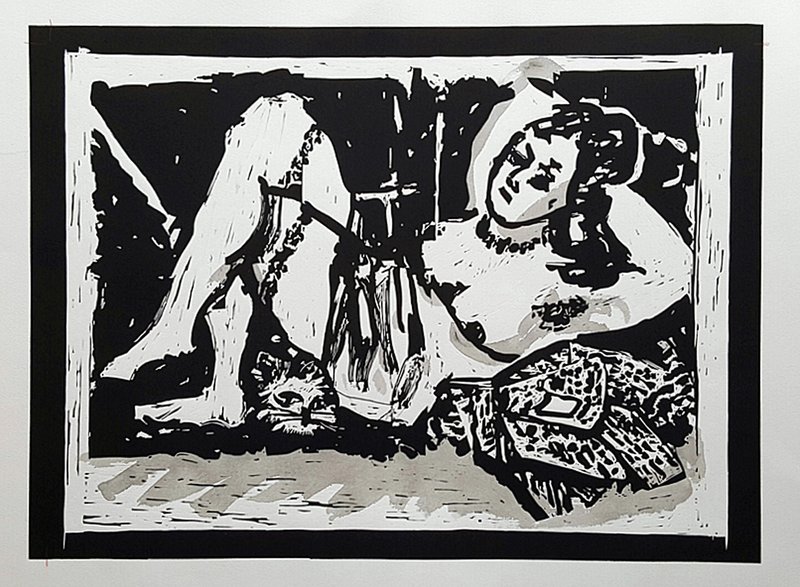

William Kentridge – Reclining Figure with Cat , 2016

Returning to South Africa,

Kentridge

was, as he later put it, “reduced to an artist and I made my peace with it."

Initially working within South Africa’s film industry, Kentridge produced his first animated work, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris, in 1989. The eight-minute-work, created from twenty-five charcoal drawings, and set to the music of Duke Ellington, the film tells the story of a battle between the evil property developer Soho Eckstein and his alter-ego Felix Teitelbaum.

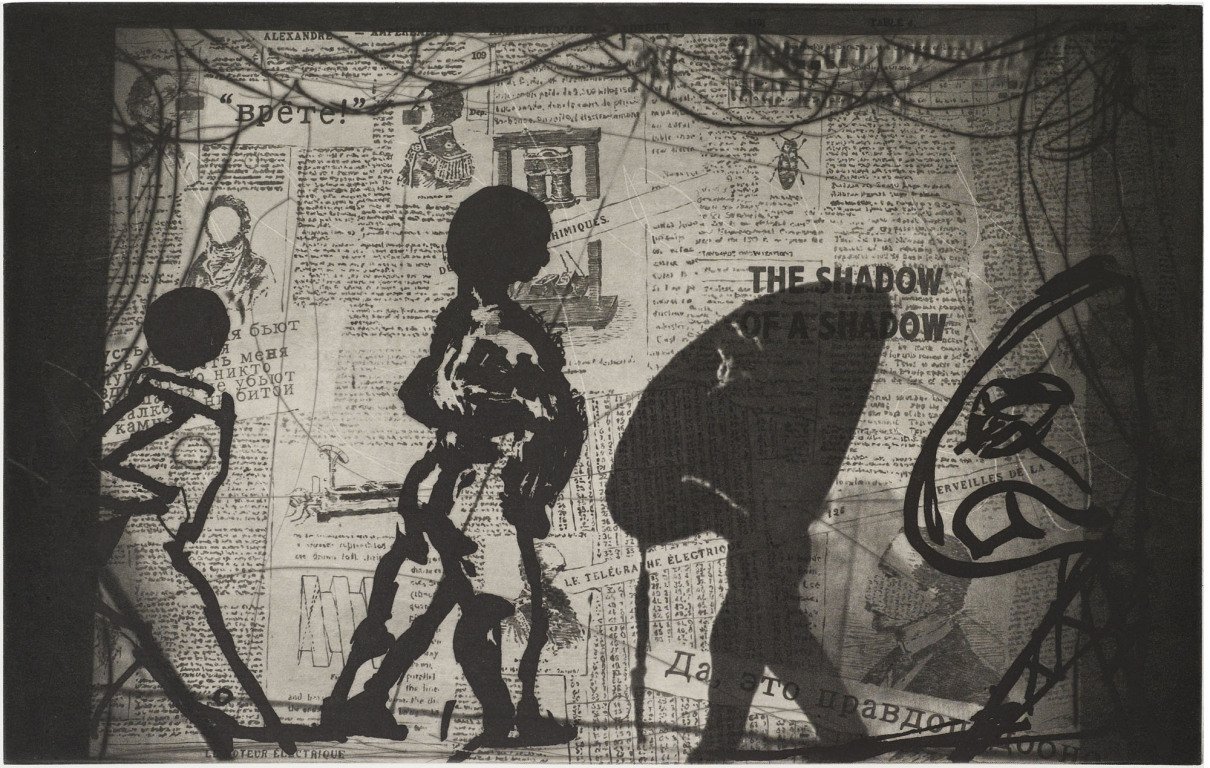

William Kentridge – Portable Monuments , 2010

“Using a stop-motion technique, each scene is constructed from a single large-scale charcoal drawing that

Kentridge

repeatedly modified with expressive, gestural marks before rephotographing it,” runs the text in the Phaidon book, African Artists from 1882 - Now. “With traces of each revision left visible, the film becomes a metaphor for the ephemeral nature of personal and cultural memory.”

Over the following decades, he widened his practice, producing prints, films, and numerous gallery exhibitions, as well as a number of acclaimed operatic productions.

In 2005,

Kentridge

directed his production of Mozart’s Magic Flute at Le Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels, creating new animations for the performance. In 2010, Kentridge directed and designed a new production of the 1903 Shostakovich opera The Nose for the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The work, which was based on an earlier short story by Gogol, describes the travails of a St Petersburg official whose nose leaves his face and takes on a life of its own. And in 2015, he returned to the Met with his production of Lulu, a 1930s opera by the Austrian composer Alban Berg.

William Kentridge – The Nose, 2010

Possibly in acknowledgment of his slightly jagged career moves, in 2016 Kentridge founded The Centre for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg: a space for responsive thinking and making through experimental, collaborative, cross-disciplinary arts practices, and perhaps just a a few early, fruitful mistakes.

Today, Kentridge's works are held in the collections of the Tate, the Pompidou, and MoMA, among many other institutions, and he is the subject of a September 2022 blockbuster solo exhibition at the Royal Academy in London - not bad work, for one of life's 'failures'. Indeed, Kentridge credits those early career dead-ends with making him the artist he now is.

"If you fail a little bit, that’s hard, because you’re not sure whether you should stop or keep going," he told Wallpaper* magazine recently in an interview to tie in with the Royal Academy show . "If you fail thoroughly, then the decision is made for you. It was very clear that I was not going to be an actor. It's not going to be. I became an artist".

Take a look at William Kentridge's artist page on Artspace here .