For stateside observers, Germany can seem like an artistic paradise; the country boasts heavily subsidized art education, a robust network of Kunsthalles and institutions, and a sophisticated base of collectors with a taste for contemporary art. This perfect storm of aesthetic appreciation has allowed Berlin to reassert itself as a global destination for culture in the decades since the fall of the Berlin Wall, but it’s far from the only German city that’s made art a central part of its identity. Situated between the former West German capital Bonn and the famed Düsseldorf Art Academy, the city of Cologne has a long history as a hotbed for creative innovation, a fact that the Vancouver transplant Natalia Hug has capitalized on in her eponymous gallery.

With a roster of only seven artists, all of them at the early stages of their careers (including international figures like Scotland’s 2013 Venice Biennale representative Corin Sworn as well as regional rising stars Jana Schröder and Carolin Eidner), Hug knows she has her work cut out for her. Luckily, as she told Artspace’s Dylan Kerr, her adopted city has plenty to offer a passionate gallerist—from its discerning and well-informed patrons to its own international fair, Art Cologne. Hug thinks Berlin’s moment may be over—read on to find out why she’s happy Cologne won’t be replacing it.

You recently moved from Vancouver to Cologne—why make such a drastic shift?

Well, I had a boyfriend who moved to Cologne in 2008, so I started visiting him quite often from Vancouver. I did that for nearly five years, and then eventually I thought it would probably be better if I just moved here. It was a personal decision, not a business one. I moved here officially in 2013, but it feels like I’ve been here forever because I’ve been visiting the city and the Rhineland for a long time.

I had a gallery in Vancouver, where I worked with contemporary artists just as I do now in Germany. My program was based on the local art scene, for the most part, with a few exceptions. That was what I found interesting. When I moved to Germany, the presence of the Düsseldorf Art Academy really excited me, so I researched quite a few people who I ended up working with now. I remained with some of the people I worked with in Vancouver, and I picked up new people—it’s a bit of a mix, a hybrid. It’s not a stagnant entity.

What is your background? How did you find yourself running an art gallery?

The story is a little bit twisted. I did my undergraduate degree in international relations, which is mostly political science, and a few years later got my masters in cultural theory—both in Vancouver. As I was writing my thesis, which I procrastinated on as much as I could, I started a gallery with a girl in Vancouver as a kind of hobby project that eventually became more serious.

Somehow it worked really well, because we found that there had not been exposure for young artists before. It was hard to do business in Vancouver, however, because there is practically no market whatsoever. It was a struggle, a great big struggle that basically destroyed us as a business partnership. I moved here after that, conveniently [laughs]. As I said, I did it for personal reasons, not business—I actually had no idea if it would work out here. It was an experiment.

How would you compare the art climates of Vancouver versus Cologne?

Vancouver is very much influenced by the Vancouver School of conceptual photography, starting with Ian Wallace and Jeff Wall. When I started showing art it was actually mostly about painting, because painting was almost a shame there. Even now, it’s a very conceptually oriented place. It’s because of the influence of amazing people like Wall and Stan Douglas and Rodney Graham, but it’s very much a ‘90s scene. Now, of course there are people like Geoffrey Farmer there—it’s great, but it’s very small.

I think the problem with Vancouver is that none of these people teach, for the most part. It’s unfortunate. If you look at the Düsseldorf Academy, the faculty is fascinating. There’s Rita McBride, there’s Elizabeth Peyton, there’s Christopher Williams—amazing, amazing artists that actually give back, and it really shows.

What attracted you to the young artists you found at the Düsseldorf Art Academy?

I have a friend named Adam Harrison, who’s from Vancouver. He moved to Düsseldorf to study with Christopher Williams—whom I know personally and whose work I really love—about a year before I finally made the move to Cologne. When I got there, he was the first person I called for advice. He helped me tremendously by introducing me to the Rhineland’s art scene, including the first two people that I started working with, Johannes Bendzulla and Alwin Lay. I still work with them now, and it’s been really fantastic to see them grow with me. That’s sort of how it works—you know one person, and from there you figure out what to do.

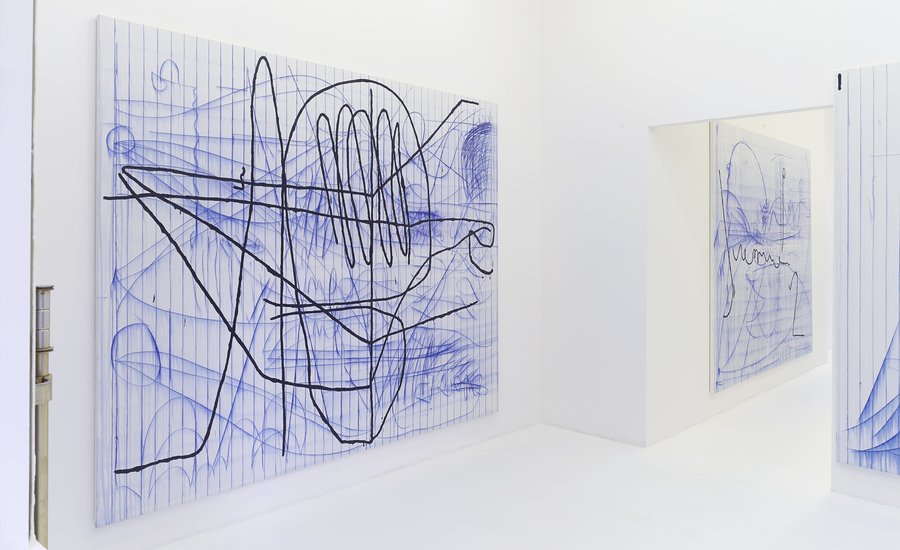

Installation view of Alwin Lay's "Prospective #5" at Natalia Hug, 2015

Installation view of Alwin Lay's "Prospective #5" at Natalia Hug, 2015

You have a roster of largely emerging artists. Why focus on artists in the early stages of their careers, and what kinds of challenges does that entail?

In the beginning, it was just about the discovery. Actually, that particular feeling of “this is amazing, this is something I haven’t seen before” is really rare, and when I see it I follow it whether the artist is emerging or not. It’s more about my own fascination with the work. As far as challenges go, it’s just a lot of work and patience.

This may change, actually—I’m turning into a more conservative gallerist, because it’s a lot of work to work with emerging artists. It takes two, three, four years to get them going. Usually it takes a couple of exhibitions and a few art fairs before they get noticed.

I have to say that the state of NRW [North Rhine-Westphalia] is quite rich with grants and different opportunities for young artists. At a gallery exhibition, you’re able to introduce the work to curators and to people who are in charge of all these platforms for emerging artists to thrive. It’s not like that in Canada or anywhere else in the world, I think.

What is the gallery scene like in Cologne?

It’s a very supportive environment. The galleries collaborate, and institutions are very interested in what the galleries are doing and vice-versa. And people do react, to new things and to good exhibitions. It’s quite critical as well, because Cologne has a great history with contemporary art. You really have to have a certain level of quality.

Does that make the climate a bit more competitive?

I’ve never really felt competitive here at all. I think there’s enough for everyone, in many ways. Of course, I don’t base my commerce solely on Cologne—there’s still Düsseldorf and Berlin and Munich, all different spheres where I can operate. I also participate in NADA Miami, which is fantastic. I diversify my financial risks in that way. My space is really inexpensive, so I can afford to experiment.

Cologne sounds like a very healthy setting for artists and gallerists—is it the same for collectors?

I think so. Collectors are quite educated here. I’ve found that if you try to explain the work to people who come to the openings or exhibitions, they prefer to not even talk to you. They read the press release and make up their own minds. It’s completely different from Canada, where I really felt like an educator in many ways. Here, people have their own opinions, which is fantastic. They either like it or they don’t, they can talk about it if they want. It’s almost intimate, the relationship between the audience and the work.

That’s so different than what you’d expect in most American galleries as well. How does this educated audience change your approach as a gallerist?

I do have to put quite a bit of work into exhibition texts, for example. I usually hire curators or people with an interesting writing style. I have to be really, really precise in what I’m showing. It has to make a strong statement. My gallery space is quite small anyway, so it’s a challenge for most artists to create that one statement because there is a lot of overproduction, which I’m trying to avoid as much as possible. The shows are as focused as they can be.

Artistic overproduction is something that’s being talked about a lot recently in the wake of the infamous art-flipping fiascos of the past several years. How do you think about this issue?

Personally, I don’t like clutter. My house has very little furniture, for instance—it’s my approach toward life. If an artist can’t deliver a statement, it’s a problem. Everything else is more about hiding the fact that there is a problem. You have to say and do a lot with very little. That’s life, you know?

How do you see your artists rising to that challenge?

Every exhibition we have is an example of this, otherwise there wouldn’t be an exhibition [laughs]. It used to be difficult to communicate that without offending the artist, because most artists want to show everything they have in the studio. Editing is my personal challenge as well. It’s a collaborative moment when you decide what to show and how, so you have to work with people.

How do you see your artists fitting together or complementing one another?

To be completely honest, medium doesn’t really matter—it’s about being relevant. Because I work with former students of Christopher Williams, they have this ongoing obsession with precision, whether conceptual, formal, or metaphorical. This is something I’m looking for. It has to be extremely concise and well delivered.

Installation view of Johannes Bendzulla's "Arctic Winter - Versus - The Warmth Emitted By Your Computer Screen" at Natalia Hug, 2015.

Installation view of Johannes Bendzulla's "Arctic Winter - Versus - The Warmth Emitted By Your Computer Screen" at Natalia Hug, 2015.

In the American art world, we tend to think of Berlin as a utopia for artists. How does Cologne compare?

Berlin is a super-international and exciting place—there’s a lot going on compared to Cologne and Düsseldorf. It’s a massive city, which means there’s a different audience, different demographics. There are a lot of collectors here that go to Berlin to buy work, but I don’t really see too many Berlin collectors coming here and being interested, other than during Art Cologne. There are a lot of people from the States that go to Berlin to look at art. It’s just not as international here.

Do you have an idea as to why that might be?

International collectors do come to Cologne—during Art Cologne, there’s tons, but I would imagine there’s not as many as come to Berlin. It’s a bigger city, and of course it’s been marketed as this utopian place for artists, which I don’t believe it is anymore. It’s as expensive as Cologne now, so I imagine that idea will wear off. I think it already has, in many ways.

As someone who’s been observing from afar, the Berlin hype does seem to be waning.

It became the most popular place, and every artist and their mother came to Berlin to open a gallery or have a studio in the hopes of getting into a big gallery. It’s all great, but I think the reality is that there’s just too many galleries and not enough collectors—this is just my feeling.

Do you think there’s any risk of something similar happening in Cologne?

I don’t think so. A lot of galleries moved to Berlin after the fall of the wall, but the collectors haven’t because they have their businesses here. I don’t think Cologne has any risk of becoming overhyped.

Or too cool.

Exactly, because cool comes and goes. This area is very stable and quite conservative. For example, I showed a sculpture at Art Cologne two years ago and I literally just sold it two months ago. It takes forever for people to think about things, but I appreciate that.

This kind of intellectual engagement by collectors seems so different from the trophy-hunting impulse buys we always hear about.

I love going to Miami because you see that insanity—impulsive collectors are the best in so many ways. It’s exciting, of course, but it’s not like that here. I’ve never really had an impulsive buy here in Germany. I think it’s very important for people to know that if they’re doing Art Cologne—it’s just a different climate in that way.

Untitled (2015) by Jan Pleitner

Untitled (2015) by Jan Pleitner

How is Art Cologne different from other art fairs?

I don’t do that many art fairs—it’s really just NADA Miami and Art Cologne. Art Cologne is just a different speed, although it seems like galleries do very well here. If they’re coming back, it means something is working. I think you have to put the time in and participate at least a few times to show your commitment. Germans really appreciate that commitment. I think Americans tend not to care if you come the next year—if it’s not you, there’s something else that’s exciting. Here, collectors really pay attention to whether you come back and make an effort.

How are you preparing for the big event this year?

For this year’s fair, we’re opening an exhibition of works by Jan Pleitner, who’s quite a popular painter right now. We are the host galleries here, so we try to open our best exhibitions during Art Cologne because there’s so much exposure and so many visitors—we’re all trying to do the best job possible.