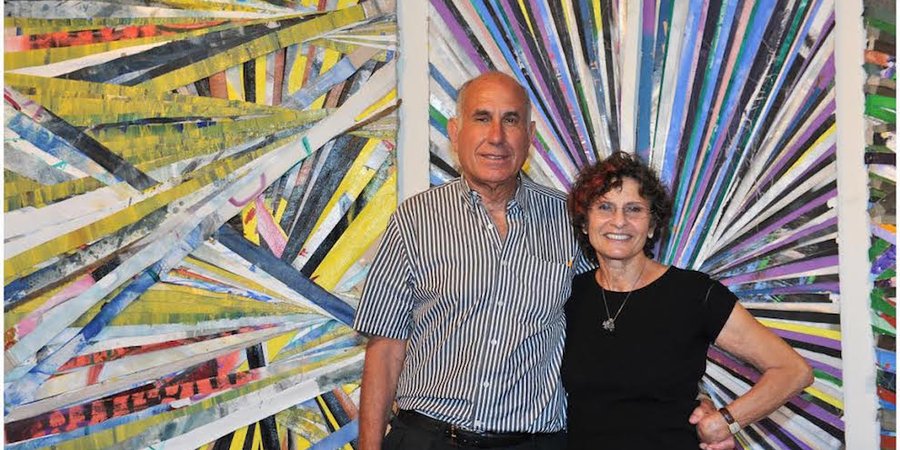

As patrons of emerging artists, Michael and Susan Hort don’t wait for museums to ratify the talents they support before buying a painting (or four)—they put in the legwork of curators themselves, shuttling out to industrial neighborhoods to inspect the still-wet work of up-and-coming artists in their studios. These visits may result in a purchase, bringing a new artistic vision into their prominent collection (which draws up to 3,000 people during their spring open house), or perhaps a grant from the Rema Hort Mann Foundation, the charitable organization they founded in memory of their late daughter.

In part two of our interview with Michael Hort, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to the collector about his recent prospecting trip to the Los Angeles art scene, the new gallery models that are intriguing him today, and which artists he is excited about now.

RELATED LINKS:

How I Collect: Michael Hort on How He Evolved Into a Collector of Influence

How was your trip to L.A.?

It was fine. It was great. L.A. is the new Berlin.

Is that the place that you’re most excited about looking at studios and galleries these days?

Yes. It’s got great art schools and it’s got some good galleries, but also there are more materials available to artists because of the art schools and Hollywood, and it’s very inexpensive compared to most locations in the world.

How would you describe the gallery system there?

There are some really great galleries out there, and there are more and more moving out there. I wonder if it’s going to work. There aren’t really a lot of collectors in L.A., so why they’re moving is beyond me. And anyway collectors in L.A. think the best art is in New York, even though it’s not.

Why is that?

They have an inferiority complex out there. They’re really think that David Kordansky doesn’t get the best Jonas Woods. It’s ridiculous. Anton Kern [who represents Woods in New York] gets what he gets when it’s his turn, and Kordansky gets what he gets when it’s his turn. In fact, he probably gets better work because he goes to Jonas Wood’s studios more. But people in California believe that New York is better off.

So the California collectors come to New York?

Of course they do. And L.A. dealers sell more in New York than in L.A.—the more established ones certainly.

What is the advantage of your going out there, then? To do the studio visits?

It’s fantastic. They have good shows! Listen, we saw the Jon Pestoni show at Kordansky—one of the best that I’ve seen this year. Unbelievable! It was just fantastic. There was also a Zak Prekop show, and a show of young sculptors at François Ghebaly, and both were great.

How often do you go out there?

Probably four times a year because the Rema Hort Mann Foundation gives art and cancer grants in L.A. We have to go quite often.

One thing that’s interesting about L.A. is that it seems there are a number of innovative new models taking root in the art market out there, like Hooper Projects, a studio complex founded by the collector Stanley Hollander and a few of his friends. The way it works is that artists—often ones without galleries—accept residencies out there and then pay for it by giving the owners a selection of the artworks of their choice. My friend Panos Tsagaris, a Greek painter, is currently out there. What do you make of Hooper Projects?

Hooper Projects is great! And I bought two of Panos’s paintings. Hooper Projects is an innovative thing, where artists from around the world—from London to Greece to wherever—come and spend three months, they give them a place to stay, they give them some money, they give them materials, canvases, whatever, and they even try to get them a gallery if they want.

A place like Hooper Projects relies on a certain amount of speculation, with the bet being that the artworks that the owners receive will go up in value and repay their investment many times over. Galleries, of course, split proceeds evenly with their artists. Why are artists attracted to the Hooper Projects model?

I was with an artist who was looking at a good gallery, and he said he wouldn’t go there because they represent almost 40 artists. I assume the reason the gallery represents 40 artists is that they’re good for art fairs and they have to do it. The artist just feels that he won’t get what he wants: warmth and comfort. This is what galleries used to provide, in terms of getting you in museums and arranging other shows. You can’t do that when you represent so many people unless you have a gallery like David Zwirner, who really does nurture his people—but he has many, many people working for him, so he can do it.

In terms of these new models, how are places like Hooper Projects selling the work? And what new avenues are galleries using to sell work?

Some of it they do online. They have no way of knowing who’s buying. If you go online people can sell to whoever they want—it can be somebody’s grandmother who’s buying it, who knows. Online creates this whole market without any guilt.

But it’s funny. I got a call from David Kordansky—he’s a good guy, we’ve known him a long time, terrific family man, he looks healthy—and says, “Michael, you’re selling your Jonas Woods?” I said, “No, not unless someone broke into my storage. It’s not for sale!”

How did that happen?

A picture is easy to get. I didn’t even know they had a picture! What they do is they call, let’s say, David Kordansky, and they say, “David, how much would you pay for this” and he gives them a crazy number. Then they go to me and they say, “We can get you half a million” and hope that I’ll part with it. I won’t, in this case. But every important collector I know is thinking about it even if they’re not doing it. It’s ridiculous!

It’s just different buying online, and you can buy anything you want basically. And there’s no way of anyone knowing what you bought.

The speculative strain that is spreading throughout art collecting has risen in tandem with the growth of the power of the collector, with collectors now able to influence markets and profit from art to a newly heightened degree. It stands to reason, since collectors are often successful businesspeople—that’s how they made the money to buy the art, after all. What do you make of this financialized aspect of the art world and the collectors who embrace it?

Well, most of them just like to win. There are people who are extremely wealthy and will buy art and not sell it, because they love the art, but they would like to know that it’s double what they paid for it. They’re so competitive at everything that they’re competitive about that too.

A year ago an email went out to members of the press that touted your family’s “proven track record of helping develop lesser-known artist into superstars,” seeing “their prices more than double.” It went on to note that, unlike in the stock market, insider information is legal in the art market, and that you [the Horts] “are the people who create the insider information.” What was the aim there?

I had no idea this was written. There’s so much happening about me that I don’t really care. As long as they don’t insult my friends I don’t really care what they say. But, listen, there’s no question that if you have a good eye and you’re smart enough about what you’re doing and you buy contemporary art you can actually make money. Something you buy for $10,000 can quickly go up to $20,000, and sometimes they can be worth millions, no doubt about it. If they knew which one they would buy it, but they don’t, so instead they buy a lot.

How do you monitor the market values of the artists in your collection? Do you have a system?

I don’t care about market values. I have no idea. I don’t track of it. I only know about market values when someone calls me and says, “You have this painting, do you want to sell it for x?” One of the things you have to understand is that our collection is reasonably public, because we let people in the house. We let people take pictures—I don’t care. So if someone has come to the house over the past five years and they take pictures, then they know about half of what we have.

Does this focus on the financial aspects of the market make you nostalgic for an era when things were moving a little more slowly?

Yes, because it hurts the artist tremendously. Some artists do well and benefit, but 90 percent of them do not. They fall apart, and it’s mainly because of prices that are hyped. When they’re new and they sell it’s very hard to cut their prices in half when they don’t sell.

To close out, what are some of the artists you’re excited about today?

Well, there were a couple in L.A. Despina Stokou shows with Derek Eller and Eigen+Art, and she just moved out to California from Berlin. California is reasonable, she has a really nice studio, and she’s doing incredibly great works. She became a California girl, she has a Jeep convertible and a hat, she looks incredibly great. She’s working like a demon with Derek Eller, and her work was in Dallas with Eigen and it’s going to be at Frieze with Derek. The preview we’ve seen is unbelievable.

There’s this other guy, Alex Kroll who shows with Friedric Snitzer in Miami. He’s doing incredible work, and he’s paying nothing for his studio compared to New York. We like Alex Olson too. She’s sending out amazing art to her gallery in London, Laura Bartlett. Great stuff, she’s got a studio, not a lot of money but the only thing she has to worry about there is water.

We saw a young guy, Michael John Kelly—incredible art! We bought a painting. We went to Jon Pestoni’s studio. Friggin’ unbelievable. You can go on Instagram and see a painting we bought from Kordansky. He has a huge studio that doesn’t cost an arm and a leg, so he can start work and then leave it on the side and come back to it. He has amazing drawings that have sold like hotcakes.

There is a great artist from Vienna, Jannis Vareles, who is also living in L.A. He’ll be showing at Krinzinger Gallery in Brussels and James Fuentes in New York in the fall. We also saw Jean-Baptiste Bernadet, he shows with American Contemporary. He was making paintings, having fun.

These guys all have big studios and they’re working like dogs there. And it’s healthy. We went and saw Hugo McCloud, whose work is up in our house now and who shows with Sean Kelly. He’s working out of Hooper for a month or two in between, and he’s very friendly with Stanley Hollander.

About a year ago we bought lots of paintings of his, and we went to visit him about two months ago at his studio in Brooklyn. He looked like he was dying. It was freezing, all the windows were shut and there were all kinds of gasses and oils and other shit. It was worse than smoking 40 packs a day living there. Now, in California, he has an open studio—he looked so healthy, so happy. I mean, come on!

I’m not saying I want to live in L.A. I can’t stand it. The cars are ridiculous. But if I was an artist I’d sure think about it, and for a few days it’s great. It’s just very conducive to working, the air is fresh.

On a trip like this how many paintings do you take back with you?

By the time I flew back on Jet Blue I had eight paintings. How many did we buy in total? I don’t know—we’re still negotiating. A bunch. We bought two outdoor sculptures form François Ghebaly that I’m very excited about. One is chained fruits by Kathleen Ryan that hang together, the other is by Kelly Akashi and it looks like a tire but it’s a bronze outdoor piece.

What do you think is the next art city that’s going to start getting traction?

L.A.! It’s just starting out there. In the ‘80s it was absolutely, 1,000 percent New York, and then New York lost some of its luster for whatever reason and Belgium was the place that got hot. Jan Hoet was the top curator in the world, he did dOCUMENTA, he did Venice. Then it went to England for a while and that was suddenly the center of the art world. And then it went to Germany, because it was so inexpensive there. And now they’re going to L.A. because Berlin started getting expensive. As soon as L.A. starts getting expensive the artists are going to have to find another place.