In Birmingham, Alabama sits a house with an unknown future. Its fate rests in the hands of a community of historical preservationists, fans, neighbors, and history buffs, who are trying to raise money to save the house, locally known as the "Pink House," from being torn down by developers to make way for five smaller homes. After digging into the history of this house, it's not hard to understand why such a battle has been waged.

The Pink House. Image via SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

The Pink House. Image via SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

Built in 1921, the house was designed by artists Eleanor and Georges Bridges without an architect. Georges, a sculpture, hand-carved many of the details that grace the building and the property that surrounds it—a little over an acre of manicured hedges, paths, and flower beds the neighbors have dubbed "the secret garden." The pink Italianate stucco home was owned by the worldly couple until 1988. E leanor Bridges, the daughter of a wealthy Birmingham real estate magnate, went to Philadelphia's Ogontz finishing school, where she bunked with roommate Amelia Earhart, who would later become world-famous as the first women to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. At one point, Eleanor was nearly expelled for missing class to join a suffragist parade in Philadelphia. At the age of 19, she met Georges, a World War I veteran, and they were married within a week of meeting, despite protest from her father. In 1923, the Bridges moved to Europe, living briefly in Paris and Majorca, before returning to the Americas to build their house in the Edgewood neighborhood of Birmingham, and set up art colonies in Mexico City and Taxco, Mexico.

Eleanor and Georges Bridges. Photo vis SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

Eleanor and Georges Bridges. Photo vis SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

During the Depression, Georges made use of his bronze and stone sculpting skills, teaching laborers to make their own works, which would later pepper the parks and hospitals of the area. Meanwhile, the Bridges took in as many as 18 children who had been abandoned in the nearby mines by parents who could no longer afford to care for them. Instead of enrolling them in public schools, Eleanor created her own curriculum focusing on art and literature, raising eyebrows of both delight and scorn from the community. (Eleanor taught formally as well, with stints at Vassar College as well as local high schools, and she taught a class at Samford University called "More Power To You," aimed at older women.) Raising the children until they were either old enough to live on their own, or were taken back by their parents after the economy had recovered, the Bridges utilized the Pink House as a sanctuary and refuge for those in need. When the children left the house, the couple made use of the spare rooms by housing recovering alcoholics, under the supervision and care of a medical doctor.

But children and the sick weren't the only ones to benefit from the Pink House and the Bridges' generosity. The house became an epicenter for art and culture, hosting writers like Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, whom the Bridges likely met during their time in Paris. It also hosted weekly Sunday-night discussion groups, as well as a rendition of Oscar Wilde's "Salome" performed in the front yard. The performance would become the inaugural production of the Valley Civic Theatre. The couple also founded a number of groups, like the Birmingham Theosophical Society, which met at the Pink House, and Eleanor was involved (either as a founder or a board member) of the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Women's Civic Club, the Women's Committee of 100, the Birmingham Music club, and the opera, symphony, and ballet organizations.

Of course, while the Bridges' mission to "beautify" Birmingham and make it the cultural epicenter of the South, many members of the then-segregated city had other, more pressing issues to fight for. Eleanor's ignorance of and disconnect from the injustices facing the African-American community is visible in the 1961 CBS documentary Who Speaks For Birmingham? , wherein Eleanor's on-camera comments about Birmingham's cultural elite are juxtaposed by those of Birmingham's African-American leaders.

Image via SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

Image via SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

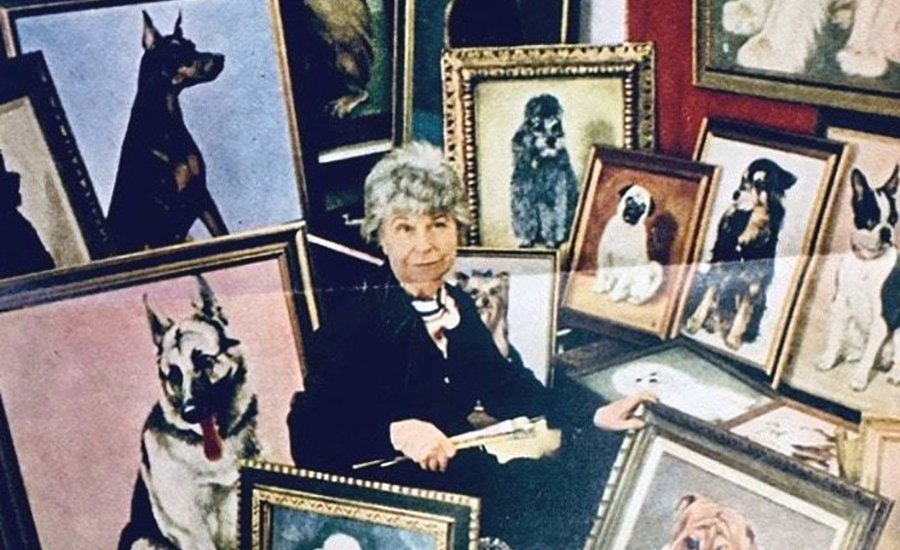

Eleanor considered civic engagement as something rooted in the arts. She herself was an artist, most known for her painted portraits of dogs and their owners. She was even commissioned to paint the pups of presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Gerald Ford, and she donated a portion of her commissions to animal welfare charities. Later, the Birmingham Museum of Art would mount an exhibition of 100 canine portraits by the artist, who worked in a studio at the Pink House. To this day, the sculptural works of Georges can be found scattered across the gardens and within the house itself.

Fast forward three-quarters of a century, and the house, for many long-time residents of the community, represents the good intentions of a philanthropist and cultured couple. But the house itself has long been absent from the art world. The Bridges have been deceased for decades, and in 1988, a couple named Eric and Diana Hansen bought the house, before selling it to a real estate developer in 2004 when they faced medical bills they couldn't afford. The developer, Pat O'Sullivan, rented the house to the Hansens until earlier this month, when his intentions to raze the property went public. The Homewood Planning Commission approved plans to develop the property, splitting it up into 6 separate lots for 5 separate homes.

Photo via SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

Photo via SaveTheHomewoodPinkHouse.com

But since these plans have become public, O'Sullivan and the Homewood Planning Commission have been the recipients of major protest and frustration. “Razing the house and secret garden will leave a historic neighborhood unrecognizable and continue our city’s troubling cycle of destroying historical sites and regretting it once it’s too late," said Dylan spencer, a member of the Homewood Historical Preservation Society. "Our plan is for the property to become sort of a miniature Botanical Gardens with space for an art gallery, free art classes, gardening, weddings, movies on the lawn—just a beautiful place for people from all over Birmingham to enjoy.”

The Homewood Historical Preservation Society has been soliciting donations in hopes of raising enough money to buy the house from O'Sullivan, who says he's asking $2.5 million. So far, they've barely raised a fraction of that amount, but the Society is hopeful that the sheer number of donations they're received (even if they're each for less than a hundred dollars) is enough evidence that the community supports the notion to preserve the Pink House and make it available to the public as a community asset and cultural center. Hundreds have taken to social media to concur, and a petition on Change.org has received over 3,350 signatures at the time of this writing.

By some accounts, a deal must be struck by February 1st in order for the house to be saved. Donations to save the structure may be made at savethehomewoodpinkhouse.com.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The Olympics Destroyed Rio’s Poor Communities—These Photos Are What's Left

Theaster Gates on Using Art (and the Art World) to Remake Chicago’s South Side