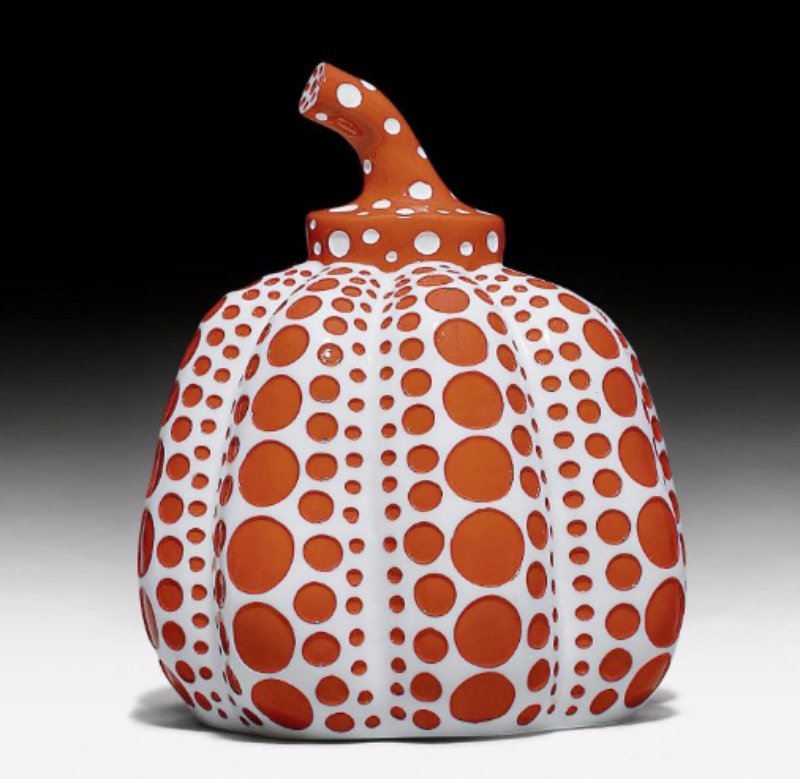

The pumpkin is to

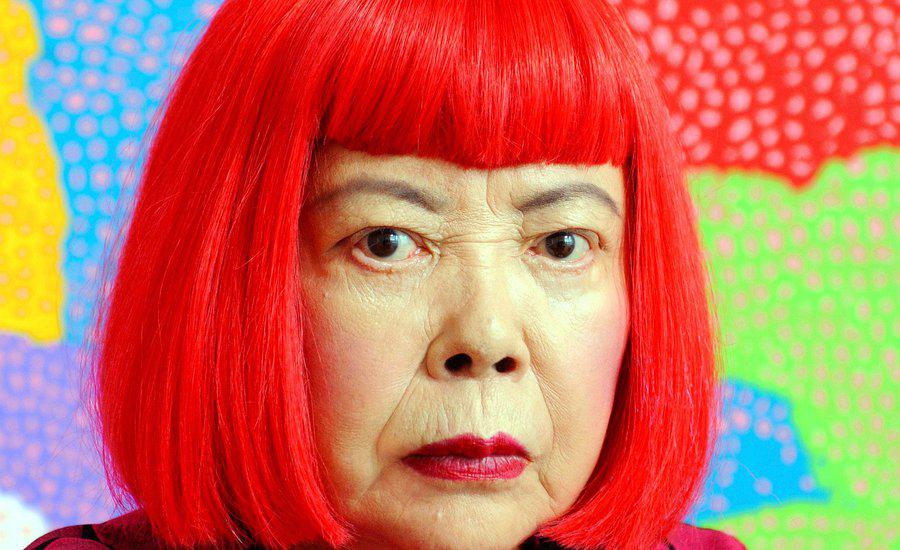

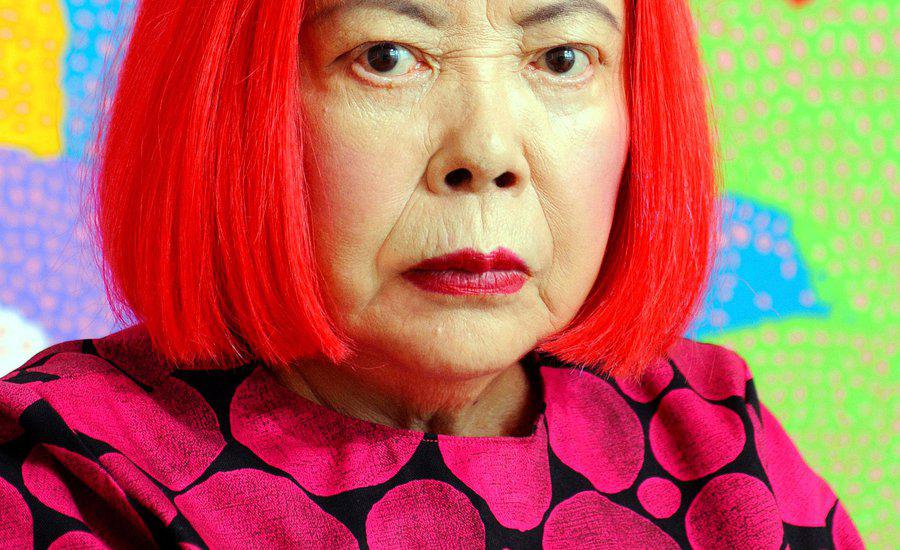

Yayoi Kusama

what the Campbell’s Soup can is to Warhol: an everyday comestible elevated to the status of fine art, via a singular artist’s skills and vision. Yet, although she is most well-known for this one item, Kusama comes with a pedigree of film, performance and ‘happenings’ stretching back the 1960s and as avant-garde as you might wish. And, like Warhol, Hockney and Haring, she has pretty much transcended the artworld to become a true icon of modern popular culture.

It’s a measure of her worldwide renown that creative contemporaries as diverse as Donald Judd and, more latterly, Marc Jacobs, have all hailed the importance of her work.

"When people look back at Kusama's work decades from now, they'll see that her idea of creation and infinity has an eternal endurance," Jacobs has said. Judd, with whom Kusama enjoyed a lifelong freindship beginning in the early 1960s, said of her paintings:

"The effect of Kusama's work is both so complex and simple. It is produced by the interaction of the two close somewhat parallel planes, at points merging at the surface and at others diverging slightly but powerfully."

Kusama’s output has transcended two of the most important art movements of the second half of the twentieth century: Pop art and Minimalism. Her extraordinary and highly influential career spans paintings, performances, room-size presentations, outdoor sculptural installations, literary works, films, fashion, design, and interventions within existing architectural structures, which allude at once to microscopic and macroscopic universes.

Poet and critic Akira Tatehata interviewed her recently for Phaidon’s Contemporary Artist Series book Yayoi Kusama. Here, we have brought together some edited highlights from a lengthy and incredibly insightful interview.

AKIRA TATEHATA:

After many years of being viewed as a kind of heretic, you are finally gaining a central status in the history of postwar art. You are a magnificent outsider yet you played a crucial, pioneering role at a time when vital changes and innovations were taking place in the field of art. However, you had to fight one difficult battle after another before you came to this point.

KUSAMA:

Yes, it was hard. But I kept at it and I am now at an age that I never imagined I would reach. I think my time, that is the time remaining before I pass away, won’t be long. Then, what shall I leave to posterity? I have to do my very best, because I made many detours at various junctures.

TATEHATA:

I would like to ask you about the period when you were in Japan before going to the US. You went to New York at twenty-seven. By then, you must have already developed your own world as a painter. Your self-formation was grounded in Japan. Still, you did not flaunt your identity as a Japanese artist.

KUSAMA:

I was never conscious of it. The art world in Japan ostracized me for my mental illness. That is why I decided to leave Japan and fight in New York. I chose America because of my connections. Besides, I believed the future lay in New York. However, I had a hard time due to the restrictions imposed on foreign exchange by the Japanese government. I even sold my furisode [long-sleeved kimonos with sumptuous designs]. Georgia O’Keeffe, with whom I had corresponded since before my arrival in the United States, was so worried that she invited me to come to her place, offering to take care of me. But I remained in New York, in a studio with broken windows at the junction of Broadway and 12th Street.

TATEHATA:

Did the various art scenes in New York excite you?

KUSAMA:

The first thing I did in New York was to climb up the Empire State Building and survey the city. I aspired to grab everything that went on in the city and become a star. At the time, New York was inhabited by some 3,000 adherents of action painting. I paid no attention to them, because it was no use doing the same thing. As you said, I am in my heart an outsider.

TATEHATA:

To you, ‘outsider’ must be a word of pride; to me, you are no mere outsider. It feels odd to say this in front of the artist herself, but Kusama can be considered as an artist who, seriously engaged with the art of her time, has been situated at the centre of the unfolding of art history, like Van Gogh. Mere outsiders could not change history.

KUSAMA:

I had no time to dwell on which school or group I belonged to. Van Gogh would have thought little of schools when he was painting. I cannot imagine how I will be classified after my death. It feels good to be an outsider.

TATEHATA:

Still, you had certain exchanges with other artists.

KUSAMA:

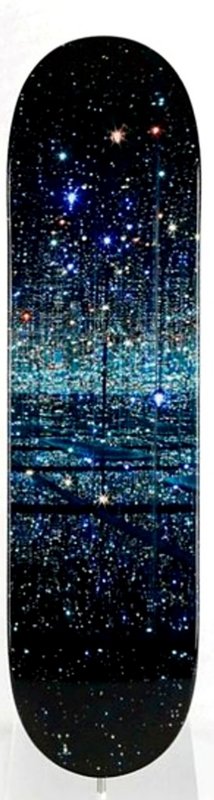

Yes. Lucio Fontana, for example, in Europe. I made some of my works at his place and he helped me with my exhibitions. Our contact lasted until his death in 1968. I borrowed $600 from him to have the mirror balls (Narcissus Garden) fabricated for the Venice Biennale in 1966. He died before I could pay him back. He spoke highly of my work; he was very kind to me. He was like that, encouraging the development of younger artists. His work is also wonderful, both his painting and sculpture.

TATEHATA:

And in New York?

KUSAMA:

I was close to Joseph Cornell for ten years. He developed an obsession for me. When I first visited him he was dressed in a ripped sweater. I was very scared, I thought I was seeing a ghost. He had such an extraordinary appearance, and he lived like a hermit. He was unusual as an artist. He, too, was an outsider.

TATEHATA

: How about Donald Judd?

KUSAMA:

My first boyfriend. I met him in the early 1960s, when he was very poor. He was studying at Columbia University and had just begun writing criticism for Art News and Arts Magazine.

TATEHATA:

He made a very accurate observation of your work. As a formalist, he keenly discerned the spatial essence of your Infinity Net paintings – their stratified structure and oscillating sensation.

KUSAMA

: Judd was a theorist. Simply put, he could not make an ordinary kind of work. In a sense, half of his work at that time was my making. He once griped, ‘What shall I do now? I am at a loss.’ I responded, ‘This, this is it’, kicking a square box that we had picked up somewhere and turned into our table. That gave him a hint for his box pieces. We were both extremely poor. As I recall, an armchair that became one of my Accumulation pieces was also scavenged from somewhere by him. He helped me make the stuffed phalluses from bed linen. Later I moved to a larger studio, separated from Judd. Larry Rivers and John Chamberlain lived upstairs; On Kawara was across the hall from Chamberlain. One day I was struck by fear while I was standing in the building. I cried out: ‘I’m scared. Somebody, please come.’ There came Mr Kawara: ‘Don’t worry. No need to be scared, I am with you.’ He lay down with me. There was no sex but we held each other naked. He helped calm down my attack. My attacks became so severe that an ambulance came every night. At the hospital they recommended I see a psychoanalyst.

TATEHATA

: What was your problem?

KUSAMA

: Depersonalization. Everything I looked at became utterly remote.

TATEHATA

: Did you have the same problem while in Japan?

KUSAMA

: Yes. When I was a child, my mother did not know I was sick. So she hit me, smacked me, for she thought I was saying crazy things. She abused me so badly – nowadays, she would be put in jail. She would lock me in a storehouse, without any meals, for as long as half a day. She had no knowledge of children’s mental illness.

TATEHATA:

How long did your hallucinations persist?

KUSAMA:

I still have them.

TATEHATA:

Is your work a kind of art therapy?

KUSAMA:

It’s a self-therapy.

TATEHATA:

Is it fair to say that you make your work in order to gain spiritual stability and release yourself from psychosomatic anxiety?

KUSAMA:

Yes. That is why I am not concerned with Surrealism, Pop Art, Minimal Art, or whatever. I am so absorbed in living my life.

TATEHATA:

You haven’t thought much about ‘isms’, have you?

KUSAMA:

Nil.

TATEHATA:

Yet people try to attach these labels to you.

KUSAMA:

Since I rely on my own interior imagination, I am not concerned with whatever they want to say about me.

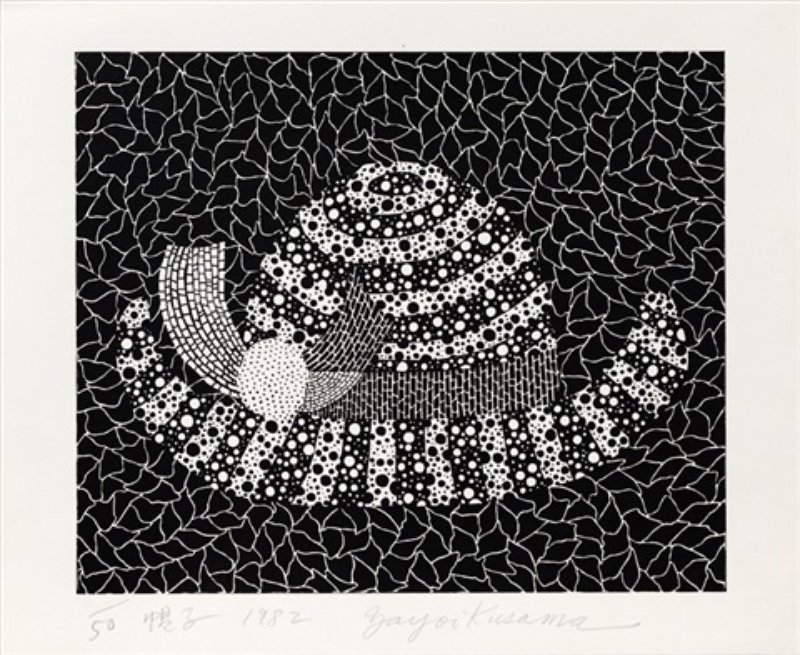

TATEHATA:

I interpret your dot motifs as representing a hallucinatory vision. In your experience, just as attacks of depersonalization bring you a vision of fear, so do these dots. Proliferating dots append themselves to scenes around you. You attempt to flee from psychic obsession by choosing to paint the very vision of fear, from which one would ordinarily avert one’s eyes …

KUSAMA:

I paint them in quantity; in doing so, I try to escape.

TATEHATA:

You have also described this process as a ‘self-obliteration’ into a world suffused with dots. Salvation through self-obliteration.

KUSAMA:

I was so desperate that I made my art during hallucinations. When I was studying Nihonga (‘Japanese-style painting’ that employs traditional glue-based mineral pigments) in Kyoto, I would go out in the rain to practise Zen, wearing only a T-shirt. I would meditate in the mud in a heavy downpour, go home when the sun came out, and pour icy water over my head. I could not work otherwise. In some ways, my New York years were no different.

TATEHATA:

Is the imagery of phallus-covered furniture related to your hallucinations?

KUSAMA:

It is not my hallucinations but my will.

TATEHATA:

Your will to cover the space of your life with phalluses?

KUSAMA:

Yes, because I am afraid of them. It’s a ‘sex obsession’.

TATEHATA:

Still, these works motivated by your interior necessity are considered to be precursors of Minimal and Pop Art. Although what people say may be of no concern to you, it is a fact in terms of chronology. Art historically, your work of the late 1950s and early 1960s was contemporary with that of the Zero and Nul Groups and what became known as the New Tendency in Europe, with its emphasis on monochrome works.

KUSAMA:

In 1960 one of my Infinity Net paintings, Composition (1959), was included in Udo Kultermann’s exhibition ‘Monochrome Malerei’ at the Städtisches Museum in Leverkusen, Germany. Mark Rothko and myself were the only two artists from America invited to participate. I made an inquiry as to why and how I was chosen and learned that the curator saw an article in Arts Magazine that discussed my work as black-and-white painting. It was on this basis that Kultermann initially contacted me.

TATEHATA:

When I say you are no mere outsider, this is not an unfounded opinion that I made up. All the more because you are an actual person who breathes the same air as we do, you were able to exert a tremendous influence. For example, you challenged the authorities of the time, as in your guerrilla event at the Venice Biennale in 1963.

KUSAMA:

Yes, what was most important about Narcissus Garden at Venice was my action of selling the mirror balls on the site, as if I were selling hot dogs or ice cream cones. I sold the balls from Narcissus Garden at $2 each. This action was done in the same spirit as my nude Happenings.

TATEHATA:

So, in an explicit challenge to the authorities, you not only exhibited but also put your work on sale outside the Italian Pavilion – until the organizers of the Biennale stopped you. I have to confess, however, that I was mesmerized by the installation itself of Narcissus Garden, which was re-created for your retrospective in 1998–99, especially when it was displayed outdoors at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It radiated a beautiful, almost sanctuary-like, light. The Rockefeller Garden at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where you staged one of your later guerrilla nude Happenings

(Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead, 1969), was at the very centre of all the American art institutions. You chose your sites very pointedly.

KUSAMA:

In the Rockefeller Garden I did body painting while my models fucked a bronze sculpture by Maillol.

TATEHATA:

Although many of your Happenings bore social messages, people tended to see them as scandals. Sacred scandals, I would say in retrospect. Did you from the beginning plan to incite a scandal or was it an unexpected result?

KUSAMA:

It was not intentional. Whatever I did tended to become a scandal or a piece of gossip.

TATEHATA:

When we think about it, these scandalous Happenings differ a great deal from your lonely toil in the studio. Whereas in your Happenings you were the leader of many participating people, in your studio you spent endless time alone, painting the Infinity Net works. It was a monotonous, solitary act. What inspired you to change your modus operandi, from the interiorized self-salvation of your early New York days to an anti-establishment, anti-institutional provocation that directly engaged society?

KUSAMA:

Since people in New York were so conservative, so narrow-minded about ex, I wanted to overturn the conventions through my demonstrations. I organized several political Happenings involving national flags. One Happening was staged in front of the United Nations building in 1968 when the Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia. I washed a Soviet flag with soap, because the Soviet Union was dirty.

TATEHATA:

Among your oeuvre, politically and socially oriented works were concentrated in the brief period of the late 1960s. You did little work of this kind before or after this period.

KUSAMA:

At the end of the 1960s I did think of continuing, somehow, in this direction. I was planning a Broadway musical entitled Tokyo Lee Story. The protagonist, Tokyo Lee, was me. Rocky Aoki and I attempted to set up a fund-raising company. We lined up the actors and stagehands, but then, in late 1969, I became sick again. So I saw a doctor, who said that it was nothing. The psychiatrists

I saw were in my opinion a mess, with their heads muddied and brainwashed by Freud. For me, they were useless clinically. I frequented them, but my illness remained as debilitating as ever. It was a waste of time. They were antiquated Freudians. All I needed from them was a piece of information about how to cure myself, which they never gave me. As they asked, I recounted to them, ‘My mother did this to me, did that to me.’ The more I talked, the more haunting the original impression became.

TATEHATA:

They didn’t save you but prompted your memory to recover?

KUSAMA:

My memory became clearer and clearer, larger and larger, and I felt worse and worse.

TATEHATA:

Towards the end of the 1960s you also founded a fashion company, which marketed radically avant-garde clothes. It was a part of your art project.

KUSAMA:

Walking on the streets, I noticed many people who wore clothes which were very similar to

my designs

. After some investigation I identified a company called Marcstrate Fashions, Inc., which manufactured them. I met with the company’s President, showed him a trunkful of my designs, and told him that his products were all imitations of my ideas. He said, ‘Oh, you are ahead of me, I didn’t realize.’ Then he and I decided to make a company that specialized in my line. It was an officially incorporated company. He was Vice President and I was President.

TATEHATA:

What was it called?

KUSAMA:

Yayoi Kusama Fashion Company. The mass media reported about us big time. We did fashion shows and had a Kusama corner at department stores. Buyers from big department stores came and selected 100 of this, 200 of that, although they only bought the more conservative styles. The radical vanguard items that I poured my energy into sold little in the end.

TATEHATA:

I have one more question that will probably bore you. In recent art criticism and scholarship, there is a distinct tendency to honour you as a great forerunner of feminist art, to interpret your work within the history of feminist struggles.

KUSAMA:

I am too busy with myself to worry about a man-woman problem. Since I find a refuge in my work, I cannot be bullied by men.

TATEHATA:

However, would you say that those who wish are free to render a feminist interpretation of you?

KUSAMA:

Yes. Although I have never thought of feminism. In my childhood, I experienced so much hardship, all thanks to ‘feminism’. My mother wielded a tremendous amount of authority and my father was always dispirited.

TATEHATA:

Your family was a matriarchy, with your mother at the centre.

KUSAMA:

She turned the entire household into her own castle. Her children had no meaning other than as existences subordinate to hers. She was smart and very strong. She was also good at painting and calligraphy. She was a valedictorian at her school. My father was dominated by her, which he disliked. He customarily went out, he was absent at home. Yet he was a very kind father.

MORE STORIES