When Sterling Ruby makes art, he doesn't pick easy subjects. "For me, I can pick subject matter that I know is going to be problematic, not only because it is corrupt or wrong, but also for the discomfort it produces by revealing some of the most troubling aspects of the American system," he tells MoMA PS1 Director Kate Fowle in Phaidon’s Contemporary Artist Series book . "It does seem important to confront America as it continues to revel in its troubles."

Those troubles, in Ruby's art, are manifold. "There are guns everywhere, and sex, drugs, and violence. This is the America of reality television – the American dream run through a blender – and Ruby gives us that world in full-blown visuality with seductive materials that blind us to the evidence of deeper forces at play," writes co-author and fellow curator Franklin Sirmans.

Big soft sculptures of planes, missiles and vampires' mouths, fashioned from stars and stripes fabric, certainly give us some insight into how Ruby – who was born on a US military base in Germany – views the country's armed conflicts. Yet, Ruby isn't some blithe, anti-American. His interest in folk arts such as quilting belies a deep love of his country. Sirmans suggests Ruby is more like a harsh, but loving parent, unafraid to deal with the dark stuff: "Everything you have to question about this country in this moment is what Ruby has been mainlining into his work for the last ten years."

In this interview, excerpted from Phaidon’s Contemporary Artist Series monograph , Sterling Ruby delves into his idea of autobiography - how his work stems from his life experiences of a rural upbringing and his reaction against being taught Conceptualism in school.

KATE FOWLE: I’ve been wondering if we can have this conversation without adding more layers of interpretation to your practice...

STERLING RUBY: Is that even possible?

FOWLE: [Laughs] I’m not sure, but I wanted to see if we could explore how your work actually speaks for itself? When people, myself included, write or talk about what you make there is a tendency to mine your influences and your background, to provide theories on your concepts and metaphors for the forms. There’s verbiage, which I think arises from an anxiety about wanting to say something meaningful or different about your practice. The thing is, I’m not sure that anything really needs to be added. Instead we – I – need to spend more time intuiting from it. What do you think? Do you feel the need to add commentary to your work?

RUBY: Less and less. I think when it was first getting attention, maybe ten years or more ago, I was anxious about how the work was going to be interpreted, and whether the context was going to come across in a way that made sense. But I have to say that was probably just because of my upbringing.

FOWLE: And now, when you’re in front of a piece in the studio, do you feel you can let it be?

RUBY: Yes, at this point, without a doubt. Lately I have found I can start a new body of work, or move through a series just thinking formally. I believe partly that’s just where a lot of artists are right now, but it’s also because my ideas, theories and contexts are already in place. So, I don’t feel it necessary to continuously lament those aspects during the process of making. Actually this touches on something I have recently been thinking about: that there is a difference between the Modernist-looking work made by someone who is forty two, forty three, versus the Modernist-looking pieces made by someone who’s twenty three. The work from people my age is really about this regression, about a kind of healing process from the 1980s and 1990s. Everybody that was teaching us at that time had been through a heavy formal training – Aesthetics, Formalism, Abstract Expressionism – which they rejected in favour of different modes of operation, such as Conceptualism. So everything they taught us was bracketed under theory and context, language, dialogue and writing.

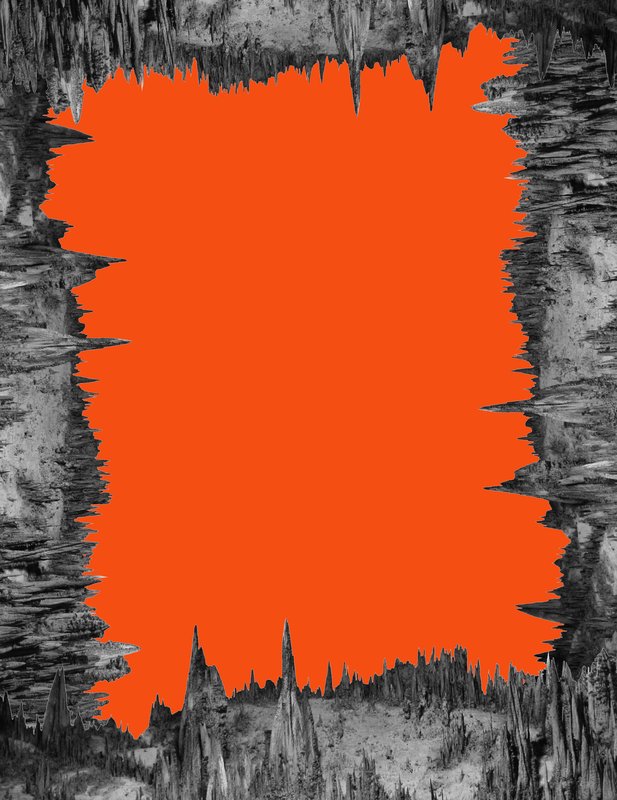

STERLING RUBY - DEEP ORANGE, 2016

FOWLE: Do you think that coming of age in the 1990s, after the generation who ushered in Conceptualism and Minimalism, has enabled you to take theory and do something else with it?

RUBY: Well, yeah, that’s the funny thing. In the United States at least, if you go to art school you have a foundation year where you learn about movements – the Renaissance, Mannerism or Abstract Expressionism – but then art history stops. The contemporary part is what you learn later on, which is also when you reject the basic art historical training you get on a Foundation Course training because you are led to believe that was just supposed to be an introduction, so it must be unimportant. My entire education was predicated on the notion that all of those precursors to Minimalism and Conceptualism were failed movements, and that the only real way to make art, or to understand the motives of an artist, was through theory and philosophy. But, because the system in which every artist is conditioned is different, now the younger generation’s impulse to think formally isn’t necessarily in retaliation to having been force-fed Conceptualism. That to me is both perplexing and interesting, especially right now if you look at what’s being made.

FOWLE: That’s what I was trying to understand in relation to you taking philosophy or art theory and doing something new or different. You’re almost using them as another material to be manipulated. In a similar way, there is something else about your works, apart from their formal qualities, that speak – almost literally through the text that you use. Take Recondite for example. I vividly remember when I first crouched down to peer inside the opening in its base and saw a message buried in its guts. And there was more, I just can’t remember it all. I do recall however that I stayed crouched down until I got pins and needles. I wanted to see if I could unlock the meaning of the cryptic handwritten words – I couldn’t – while also taking pleasure in the fact that I wasn’t even sure if I was supposed to be seeing the innards at all. That was in 2007. When I think back to the experience now, it seems to be the moment when I thought perhaps everything needed to comprehend your work was in the work, even if it was through ‘free association’.

RUBY: It’s true. The words from the interior of the Recondite sculpture were my own free association and deliberate misuse of words and imagery from a branch of mathematics called catastrophe theory. These mathematical ‘catastrophes’ demonstrated through diagrams the way in which objects or shapes could lose their structural integrity. The diagrams were always labelled and titled based on the shapes of arc and the curve that mapped out how a catastrophe would occur. So, elliptic umbilic’, was a kind of catastrophe. I was taking the imagery and ‘catastrophic’ language of the theory, and making it my own. I have always liked things like that. I guess that’s what I picked up from [Gilles] Deleuze and [Félix] Guattari; that you don’t have to read everything, or to take it at face value or reiterate from page one. You can pick and choose what you want and contextualize it within your own meaning.

FOWLE: Yes. And in that moment, you, the artist, disappear and the works exist independently. The object becomes more than a sum of the parts that you have formally constructed.

RUBY: Definitely. Look, I’m sure that this is just my take on it, but if there’s a political artwork or political poem, it takes a stance, right?

FOWLE: Yes.

RUBY: It has prejudices. It has a message. It represents a kind of opinion. I think that’s actually how most of the world operates, you know, there are biases and sides. But, when you take, or make, something that’s more abstract, how can it border this representation of a perspective and also be something completely else? Can something be liberated in such a way that it doesn’t have to take a side; it doesn’t have to have a bias? Or maybe it takes too many sides, with multiple personalities, multiple agendas.

FOWLE: And at the same time communicate something?

RUBY: Maybe it’s reflexive of certain topics, but it doesn’t have to speak. I think that’s something I understand a lot more than I did ten years ago. My work can operate under more than one principle. It can catch, hold and contain an idea, but it doesn’t have to communicate it. It can also operate formally.

FOWLE: How does poetry relate to this?

RUBY: I think the poetry that I find most successful holds its potency in the same way that art does, wherein you cannot say, ‘this poem works because it has A and B, then via some equation the catalyst of the poem is C’. It can’t be broken down like that. You can’t explain why it works. You can’t prove why it works. So, you are right about the verbiage. People are trying to manically figure out why something does or doesn’t work, because there’s obviously something that gets under your skin, which drives you to clarify what it’s doing. But because the baggage of context is so heavy these days, we struggle with it.

FOWLE: Does it come down to using gut instinct?

RUBY: Yes, but you can’t prove instinct either. That’s what’s so great about it – and also the problem. I prefer to allow myself the freedom of not consciously limiting where the work is going to go based on something that I have researched, written or thought about. I’m just as interested in leaving room for ‘failure’, so that a work can wind up becoming something completely different from the intentions I started out with.

FOWLE: How does this relate to your Desktop Folder project?

RUBY: I’ve been building a number of archives for as long as I can remember. I guess I think of them as research and development. I’ve got collections of objects and materials, as well as a series of image archives. There are hardcopy versions, because maybe I was in the doctor’s office or something like that and I ripped pages out of a magazine, or cut out images from books. These are scanned. Then there are the pictures that I have taken that also wind up getting mixed in with everything else. Others I find online, some of which are as simple as screen grabs. Then, around 2009, I started making the various archives into an image database, which was part of my private website that the public couldn’t access. That’s when I started to identify the links between all of the things I was collecting. Most of the connections were via images, but there were also particular kind of searches that I realized I was using. There was a plethora of searches that didn’t result in what I was initially looking for. When I started to structure everything online it became clear to me that it was a work in itself.

FOWLE: And now anyone can access the images on your website and you have produced a book from them. What made you decide to make the material public?

RUBY: When I first started the site people kept talking to me about ‘protecting my images and my data’. But I was also seeing another generation’s version of dealing with images, which is basically about access. So, after a while I began to think that it would be more interesting to just give everybody access to the archive. I also liked it because it seemed like a vulnerable gesture to me: showing your audience not just your work, but also the images that might have acted as a catalyst.

FOWLE: Browsing through the book, I realized how strangely perambulatory these archives are, within quite a precise terrain. They provide a visual lexicon for your work that broadens understanding of the forms.

RUBY: Yes, and I started to really like that kind of abstraction. I was fascinated by how the computer could dictate how abstract a search was going to be.

FOWLE: What do you mean by ‘abstraction’?

RUBY: Well, you might put a term into the search engine, but if you don’t define specific details – such as date or location – the images produced are rapidly abstracted.

FOWLE: So if you searched ‘East LA graffiti’ for example?

RUBY: A search for ‘East LA graffiti’ could yield an image of a wall in Iraq tagged by someone in the military from LA. Alongside that there might be images from some sorority in Idaho, making gang signs and dressed as the Crips and the Bloods during their pledge week. Numerous images are returned together that don’t necessarily illustrate the very specific agenda of your search term. So I started thinking that, via the Internet, images and our associations with them are becoming abstract. In a way, it has changed the meaning of abstraction. Abstract used to be ‘no content’. Now I think it might mean that content is obliterated.

STERLING RUBY - Untitled, 2005

FOWLE: Did this change the way you looked at your own work, or affect the process of making it?

RUBY: I liked the framework it provided me for references. I could use it in a way that helped me create more distance from any specific topics, like the prison system for example. At the same time it allowed me to still identify a context, but with more fluidity. I also started to see visual cycles and repetitions, picking out colours or shapes that I otherwise may not have considered before.

FOWLE: There also seems to be a connection to archaeology?

RUBY: Archaeology was an immediate link, both conceptually and visually. It came out of a shift in how I was thinking about the prison system as allegory, a repressive state, as if the prisoners were buried alive. The California Department of Corrections has aerial views of all their prison facilities on their website. I made a visual connection between these images of the prisons and documentation of archaeological dig sites. Then I realized that’s how I looked at and viewed potential works in the studio – looking down from a ladder or a forklift – and I started to think of these works as topographies. Then I thought, what happens if you treat the studio as an archaeological site or the various spaces as graves and the remnants as things that had been buried?

FOWLE: You mean the work is like evidence?

RUBY: Yes, evidence-like forms. Then, when you flip that topography – which is what I did with the wall-mounted basins – you don’t identify with ever having been able to look down into it. It completely changes your relation to it. Not only have you reassessed the content of the piece, but you have also changed the way that it is viewed.

FOWLE: Yesterday when we were talking about the ‘Mobile’ works, you said ‘I started making a few of these, and then the narrative came in’, what did you mean? Is this a similar realization to what you have just described with the shifting topography?

RUBY: It’s different. I don’t necessarily know if I can even pinpoint it actually. Where to begin? You can pick and choose materials for their formal value, or in terms of their autobiography: their history. The ‘Mobiles’ were a way for me to create a context for things that were personally important, but to use them formally. I started making them in the drawing studio, which is where I have one of the biggest archives, because I pick and choose visuals that I am interested in and store them in a flat file there. Then, over time as things come back out, they might not mean the same thing to me that they did when I initially grabbed them, but their history is always inherent.

FOWLE: So do you mean a visual narrative kicks in rather than one that is verbal or textual?

RUBY: That’s exactly right. The thing with the ‘Mobiles’ is that maybe I used something simply because I like it in terms of the graphic or because of the colour, but then other collage elements might have been collected years ago ...

FOWLE: For a specific purpose?

RUBY: Exactly. They are a re-emergence of specific ideas from the past. For example, the Regency drug tests. I bought those seven years ago because I was interested in the way that the American government is treating drug addiction and how workers were always being checked for chemical abuse. But I pulled them out again later and started using them in a completely different way. The tests are all based on these colour systems and identifiers, so I am now using them more for their formal qualities. So they embody this collision... I guess that’s what I was talking about with a visual narrative. The textile paintings and the fabric collages have a similar thing going on. I can work on those just in terms of form and colour and it’s total freedom, but I know all those piles of fabric come from very contextual backgrounds that will always somehow be in the work. It’s a way to drop the baggage of context and keep content.

STERLING RUBY - Untitled, 2007

FOWLE: Is this what you are doing with your own biography too? In a recent conversation with Paul Schimmel you really surprised me when you said: ‘I’ve come to terms with autobiography now’, because I know it was something you disliked engaging with for many years. When I heard that, I thought ‘Really!?’ But, to be serious, is this what you were implying, that your biography is now archival material of a sort that you can work with anew?

RUBY: Yeah, it is a bit. Again, going back to my education, I was taught that autobiography was an outmoded source of production. You just didn’t do it. But, as I said before, that leads me to think that the way we were being taught was actually what was outmoded. Throughout history, biography meant something to artists and to audiences, but then you weren’t supposed to use it? Suddenly art-making had to have a distance, to be more clinical and theoretical? God forbid you made something that revisited something from your childhood!

FOWLE: It’s interesting, because I understand what you are saying, but when I look at your work, I don’t think I need to know your personal biography to get something out of it. It’s not as if you are using references or materials that have to do with identity politics, or at least not to my knowledge.

RUBY: When I say I’ve come to terms with autobiography I mean, I guess, that I don’t really mind interpretation. But I am thinking about it for myself. It’s how I process the different scenarios and experiences, which are primarily historical, but I also have my personal relationship to them, or engagement with them. I feel like the ‘STOVE’ artworks that I am making now come out of my having grown up on a farm with a stove. My ‘BC’ collages were initially about trying to make a quilt, which also came from living in a rural area and seeing Amish quilts and crafts. So I do see autobiography in how I identify with various materials and can kind of pinpoint precursors. But then when it’s done, I don’t have a problem with it being reinterpreted without my autobiography. So, maybe it’s that I know for me it’s important when I work, but once pieces go out of the studio, it’s less important. It’s like there is a set of rules and regulations in the way that the works are developed in the studio, and then another for how they are thought through later amongst an audience.

FOWLE: Right. But I’m still not sure they have to be interpreted later? That’s really what I meant about the language that your work gets shrouded in, which I think is some kind of unnecessary reflex. Don’t you think that the materials you bring together, or the objects you create – through their contradictions and the kind of built-in logic you are using to combine and produce them – hold resonances of their history and your thinking long after you have done with them?

RUBY: Right, right.

FOWLE: Furthermore, by the time they are in a gallery they are something in and of themselves, as you said, formally, but also viscerally. As a viewer, to interpret them is to distil their power. I guess, just as you were conditioned in certain ways at art school, we as audiences have been conditioned to explain, justify or describe away everything we are drawn to.

RUBY: I agree.

FOWLE: Can we talk about the STOVES a bit more? They seem to be adding another dimension to this topic, perhaps in a way that the ‘Mobiles’ are also doing, insofar as they introduce movement into your work, or at least the potential for it. Your project for the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea in 2014 featured a number of the ‘STOVES’ functioning for the first time in an installation.

RUBY: Usually I don’t show them burning in exhibitions, for obvious reasons, and so they are almost like relics. For Gwangju I wanted to deal with the kinetics and the smell of burning wood: to think about what a performative sculpture is. But really the stoves come from ideas of utilitarianism and how things function. I grew up constantly feeding the stoves on the farm during the winter and fall months. It was a routine. I identify with the design of these cast iron stoves with their great, heavy-handed construction. Sometimes they were really flat and monochromatic, sometimes ornate. I wanted to push their forms into a sculptural dimension.

Sterling Ruby - Black Stoves, 2014

Sterling Ruby - Black Stoves, 2014

FOWLE: It’s funny that you imagine such solid works to have potential as performative sculpture. It will be interesting to see how you process this through future iterations of the work. Regardless, what I realise is that Asia does seem to have been the place that has afforded you different opportunities to experiment over the years. I remember when you started developing some of your large-scale ceramics, and more recently, the stories you told me about the process of making the bronze basins in the foundry?

RUBY: Yes. When I was making work in the foundry in Beijing there was a real enthusiasm that I haven’t experienced in a long time. There is a real energy to those works, which came from the people who were producing them and the situation in which they were doing it. Often in the States or in Europe, I find that the attitude is ‘let’s just get the job done’. Even in China I’ve been told that most artists don’t do what I did at the foundry: they don’t come in to make the work on site before casting. Instead they send a rendering or a model to work from and so there’s no interaction with the artist and the team, which I think changes the result. For me there was something about being there and making something that I didn’t have any preconceived plans for. It was also the chance to become closely involved with the process and to take the basins to a whole other scale. Then, the intensity of having everybody around me watching what I was doing was another scenario that pushed me, and stopped me from being caught in a ton of contemplation. I think I responded in a different way to how I would have done if I were working in my studio. To go back to your question though, I don’t know specifically what it is about Asia that I like so much. I mean it could just be that it’s a contrast and contradiction to the way that I understand art, which feels pretty good. It is a big challenge to get my head around it all though. The speed of the production is one thing, but labour conditions are another. After having observed it first hand it’s not possible to say I agree with the working conditions in China.

FOWLE: Perhaps this is where the notion of ‘transversality’ – which a number of people have emphasized as important to your work – has resonance, insofar as there is an inherent contradiction in the way that things you don’t necessarily agree with produce things that you are fascinated by. Then the sum of this tussle produces something other? Is the contradiction in your experiences in China similar to your interests in the Supermax prison systems?

RUBY: I guess it could be similar. There’s never going to be an agreement that this is positive subject matter to work with. If you make something positive out of it, or use it to ends that don’t necessarily criticize the system outright, you inevitably take a stance that is somewhat hypocritical.

FOWLE: But in the case of the foundry, you are exposing how the workers are using ancient techniques, talking publicly about their particular skills and energy, and I assume not exploiting them. In this way they become people, not another faceless statistic?

RUBY: That’s right. But from the other perspective, I guess for some people it makes art that can be seen in a negative light. I remember very early on identifying with Bruce Nauman as an artist who was extremely self-reflexive, but who could seem hypocritical in how he used subject matter such as abuse and abandonment in his work. This has been written about in such a way that he is implicated as positively identifying with those things. But I don’t think that he identifies with them because he thinks they are a positive. I think he revels in the fact that they are disturbing and that’s why it’s so impactful in his work. For me, I can pick subject matter that I know is going to be problematic, not only because it is corrupt or wrong, but also for the discomfort it produces by revealing some of the most troubling aspects of the American system. It does seem important to confront America as it continues to revel in its troubles. For example MSNBC, a mainstream liberal news channel, still broadcasts a show called Lockup, using hours of footage documenting the lives of inmates within the American prison system.

FOWLE: So you want to highlight or amplify the contradictions?

RUBY: Yes, but I recognize that in America there is a fine line, especially when you understand that as a culture, often the response to negative aspects of the system is to retreat to platitudes about morals and family values. In this way nothing critical is achieved.

FOWLE: Let’s finish by talking about some of your exhibitions, because my impression is that you spend a lot of time thinking through how to stage works, or at least how to activate the space in which the audience experiences them. For instance, the space for your solo show at the MoCA Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles in 2008 was incredibly awkward. You stacked and draped works in a way that not only pushed back on the space, but also forced people to reconsider their relationship to the works in proximity because they were so on top of you. Then there was the exhibition of soft sculptures in ‘Unlimited’ at Art Basel recently, which were also piled up and quite confrontational,but in a very different way. There the space evoked the carefully ordered chaos of a storeroom temporarily opened up for an event, which in the context of an art fair, left visitors wandering around with slightly bemused looks on their faces. I didn’t see the show in Bergamo, but from the photos it looks like that created a similar tension, albeit for a different reason again. There the works appeared to consume the galleries by creating blockades and barriers. Yet in terms of scale the works weren’t necessarily huge but instead existed at a size that is hovering between large and human scale?

RUBY: Yes, those installations penetrated the entire space, although the same kind of questions arise with a more intimate gallery. Do you push the proximity by creating a situation that makes you aware that the space is so small, or do you go for an approach that is more traditional, where you have to get up close to the work in order to see how personal it is?I do enjoy the process of making exhibitions, but I’ve been giving myself less and less time to install. A show like the one I did at Hauser & Wirth in New York took four days, whereas a few years ago that same install would have taken two weeks. I guess logistically I know what it means to get work into a space now, but I also think that I work better by thinking through things in advance, intuitively shifting works around at a fast pace when I am there, and then letting it be, rather than second guessing decisions.

STERLING RUBY - Phaidon Contemporary Artist Series monograph

FOWLE: That main gallery at Hauser & Wirth is also quite a difficult space, which is something you seem to thrive upon. Visitors enter from one corner and have to leave the same way, but then there is another open doorway directly opposite where you come in, which naturally draws people’s attention, so there’s no natural dynamic established within the space itself.

RUBY: That’s exactly right. It’s like you have to somehow get people to turn around in the space. I quite like that. Generally from a logistical standpoint I really like the problems of architecture. It could be a super small, tall or big space but there is always something to push against or work with. I lamented the Hauser & Wirth gallery for months. How do you install in a space like that? It was like being under a train track – top heavy, quite dark and yet so expansive. We had the dimensions of the beams posted in every studio and looked at them day in day out, because something told me that the show had to be taller than that lattice. I knew that you had to look through them to see the entire expanse of the work, because that would create an experience that seemed off, but would also start to crush, or at least flex the architecture. I don’t think people always get that about the work – that it’s not just about making big objects for big spaces, or small works because of a particular medium, but actually an exercise in producing work for certain situations. To go back to the New York show specifically, the other thing I did – to deal with the size of the space without creating partitions – is to put together pieces that wouldn’t necessarily work with one another in simple terms. So there was a soft-sculpture with a sheet-metal work, and there was a spray-painting work with a cardboard collage. Formally they created schizophrenia among the mediums and aesthetics, which was palpable when you stood in there.

FOWLE: Yes. When I saw the show at the opening my immediate impression was how uncomfortable people seemed around the work. They didn’t quite know how to physically respond to, or be in the space, which is something I’ve seen happen at other openings you have had. But, when I went back later my first thought was actually how straightforward the installation was in comparison to other shows you’ve made; there was nothing to really make you feel uncomfortable. However, the longer I stood there, the more I understood how incredibly intense the works were. Walking between them I thought about Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and the idea that artists assault the senses of the audience to get them to feel otherwise unexpressed or subconscious emotions ...

RUBY: [Laughs heartily]

FOWLE: Seriously! Works of bright, primary colours and beautiful forms surrounded me, but they were also hissing and restless. It seemed that they were installed to be traumatized and traumatizing. I felt the objects were putting me in a situation where I was becoming agitated and anxious, but I also knew it couldn’t be the objects doing this because they are inanimate. So the only way to comprehend this weird atmosphere was to work out what was making me think like this, to confront what my problem was. What was it that made that happen? Do you know what was going on in there?

RUBY: I think it’s similar to what happens in the studio. No matter if it’s new work, or old that I am looking at again, or a series I am trying to reinvent because it’s not going anywhere, I always want to hold on to that discomfort of not coming to terms with something about a piece – its tension. The original Alabama electric chair, or ‘Yellow Mama’, is a perfect example. When I saw reproductions of it, I thought it looked like a Gerrit Rietveld chair. It is a yellow, almost Constructivist or Bauhaus-type, utilitarian chair, which also looks like a Transformer from a Michael Bay film. How do you reconcile that with the fact that you know it is one of the most horrific objects in America’s death industry, and that it was built by the prisoners, and the reason for the marigold yellow is not an aesthetic choice, but simply because they used the same paint that they used to make the lines in the street with? With Big Yellow Mama, I created this large, public sculpture that looks innocent and playful and yet it comes from such sinister origins. Making art out of this loaded object opens up a whole can of worms.

FOWLE: And then you put it in an exhibition next to The Cup, a piece that is way over scale...

RUBY: Right, next door to a cup that’s made so that you don’t know whether or not it’s in a scooping or a pouring position. And then put those next to TROUGH...

Sterling Ruby - Trough, 2014

Sterling Ruby - Trough, 2014

FOWLE: Yes. Tell me about TROUGH? It was one of the objects that made me think about archaeology in the show. It looks like a cross between a grave and a small bed.

RUBY: It was a completely utilitarian object that we had in the studio for years to catch the urethane when we pour it from the platform, so that you don’t have to scrape it off the floor. Then one day I realized that I really liked the form. These scenarios are the exact opposite of how I was trained to make art, just like screen grabs in the Desktop Folder of images that immediately arrest me: totally unplanned. The Cup was originally a completely different sculpture, which wound up being too large to fit through the door and so I started cutting into it. I realized it was this huge vessel and I decided to make something that was totally identifiable, which was hard for me at the time. It’s easier now for me to say: ‘I’m on the fence about this because it is identifiable, this is straightforward and that is simple.’ I was always told: ‘Don’t use that universal because it’s too easy’ and now I say, ‘No, that universal is actually

difficult’. That’s the reason why you need to use it, because if your first reaction to it is, ‘Yeah, it’s a cup, I get it,’ then you’re like, ‘Why a cup? What does that mean?’

FOWLE: Then if that isn’t enough confusion, there is a huge basin hanging on the wall that is a bit like something from a tank and a soft sculpture that is a kind of figure that’s been hanged...

RUBY: Actually it’s two figures copulating ... again these are playful and simple materials and forms, but then they appear unhappy and restless.

FOWLE: Exactly. That’s when I thought, ‘My God, I need to tread carefully between these characters’. There’s a real tension that gets brought out between them and yet at the same time they are all lined up and frontal facing, as if in a regiment.

RUBY: Yeah, yeah.

FOWLE: Perhaps this is why at your openings people instinctively know that they are in the midst of this drama, even if it’s too busy to really see it. This underlying tension is where the widespread feeling of awkwardness creeps in.

RUBY: That’s good! But, I think it’s also about what stance you take as a viewer, because the installations make clear that your physical presence in the space has a consequence. Are you supposed to embrace this sensation? Are you supposed to reject it? Is the rejection actually the fact that you are embracing it? There are all of these different reactions that could happen, none of which are spelt out, or made clear in terms of which is right.

FOWLE: And I guess that’s what I was feeding off when I experienced the vaguely uncomfortable feeling that the works engendered.

RUBY: Yes. That’s important I think.

FOWLE: Now I’ve contradicted myself and entered in to a whole interpretation of what your works were doing in the show, which was exactly what I was trying not to do! So, I guess the answer to our initial question is: ‘No, it’s not possible to have a conversation about your work without adding yet more layers of interpretation.’

RUBY: [Laughs]

FOWLE: But, although I keep wrestling with the fact that I seem to always end up making a ‘read’ on the show and the works, I can’t help but think there is something that induces this. Perhaps it is to do with the fact that they successfully convey what you were describing as that ‘unevenness’ or ‘discomfort’ which you are also confronted with in the studio?

RUBY: I hope it is always true that each piece has a life of its own. I want the work to be schizophrenic, to defy and contradict how it is read, to shift in meaning, both inside and outside of the studio.