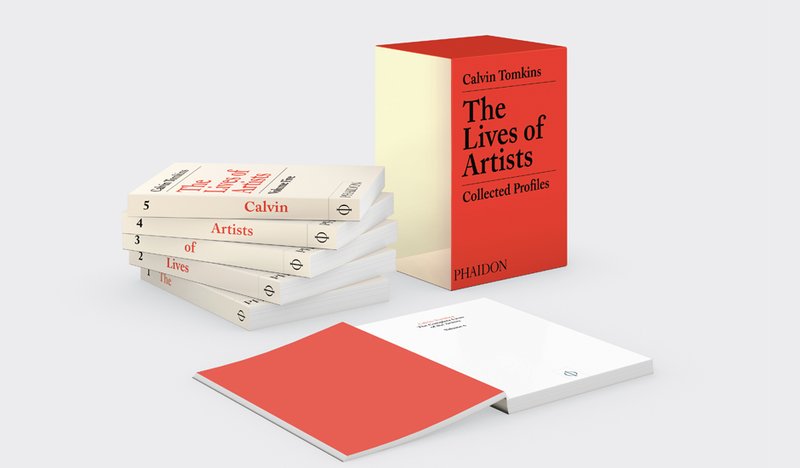

In 1959, the now-legendary journalist Calvin Tomkins interviewed Marcel Duchamp for

Newsweek

, beginning his six decade-long career writing about art. He then joined

The New Yorker

, where he has contributed dozens of profiles on the most interesting artists of the time, from from

Jasper John

s

to

Cindy Sherman

and beyond. Phaidon has recently published

The Lives of Artists

, a six-volume collection featuring 82 of his most significant pieces from 1962 to present day. Part art history, part human interest, this set is a must-have for any art lover (and makes a great gift for the holidays!) but in the meantime, read an excerpt from a profile entitled "Getting Everything In" on the artist

Jennifer Bartlett

, initially published in the April 15, 1985 issue of

The New Yorker.

The Lives of Artists is available on Artspace for $87 (on sale from $125)

The Lives of Artists is available on Artspace for $87 (on sale from $125)

Early on,

Bartlett

was profoundly influenced by Sol LeWitt’s Paragraphs on Contemporary Art, and today she is perhaps best known for the gridded work Rhapsody, a monumental installation that was first exhibited in 1976. The work was triumphant on account of both its new, imposing scale and its composition (a pastiche of individual paintings in various art-historical styles), which essentially surveys the possibilities of modern painting. Each element of the installation is painted on a baked enamel and steel plate, and while together they comprise the larger work, each plate can also stand alone as an autonomous piece—Bartlett employed this type of gridded installation on multiple occasions, and works of this sort are therefore evident throughout her oeuvre. Regarding her subject matter, Bartlett is noted for her treatment of familiar American imagery such as houses, trees, and white picket fences; she is also known to veer into non-figurative territory via explorations of geometric or painterly shapes.

Read the excerpt below, written by Calvin Tomkins.

...

In the summer of 1975, Bartlett arranged to house-sit for well-to-do friends in Southampton, on Long Island’s south shore. In exchange for taking care of the garden and the main house, she had the use of a small cottage on the property. She soon became so absorbed in her work that the garden dried up. Bartlett had laid in a large supply of her steel plates (more than a thousand), with which she planned to make a painting “that had everything in it.’ This idea had been knocking around in her mind ever since the Reese Palley show, in which it had been so difficult to tell where one picture stopped and the next began; the show might almost have been a single painting, she thought, except that it had not been planned that way. It struck her now that she could organize and orchestrate a really large work whose effect would be like the experience of a conversation, in which subjects are taken up, dropped, and then returned to in a different form, with many voices and interwoven themes. Since the conversation was to include “everything,” she decided that it would have both figurative and nonfigurative images, and that they could appear in small scale, on individual enameled squares, or spread out over a great many squares. She picked the first four figurative images that occurred to her: a house, a tree, a mountain, and the ocean. (Later, she greatly regretted the tree, which she claimed to find banal, but she refused to alter her original decision.) The nonfigurative images she chose were a square, a circle, and a triangle. There would also be color sections and sequences, sections devoted to lines (horizontal, vertical, diagonal, and curved), and several different methods of drawing (freehand, dotted, ruled). These and many other basic decisions were reached in her workroom in Southampton, including the decision that she would make up her mind about retaining or discarding a specific plate within one day of finishing it. “I didn’t want to get involved too much with thinking about the piece,” she told me. “If I didn’t like what I’d done each day, I’d just wipe it out. I wanted to piece to have a kind of growth that was actual rather than aesthetic.”

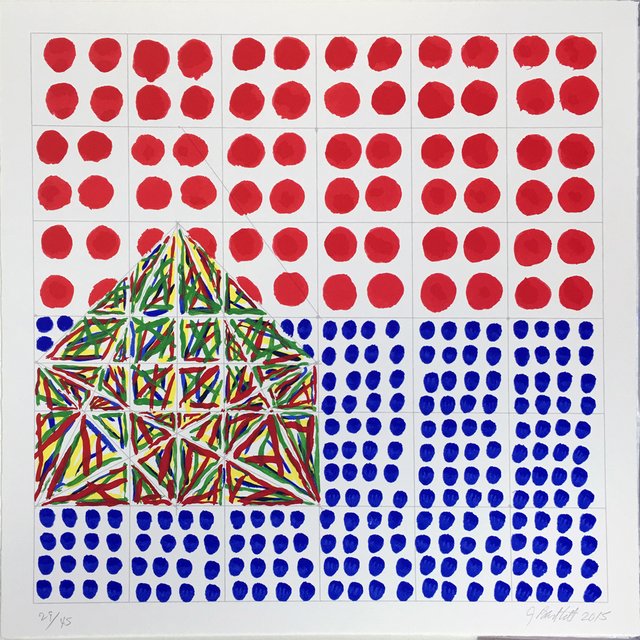

House II, #3

(2015) is available on Artspace for $3,000

House II, #3

(2015) is available on Artspace for $3,000

Bartlett finished the first hundred-odd plates in Southampton, and the rest—there were nine hundred and eighty-eight in all—in her New York loft that fall and winter, often working twelve or fourteen hours a day. Many more hours were spent in library research. She read dozens of books on trees, and dozens more on mountains. Although the figurative images she used were very simple ones, she wanted to show an essential tree and an essential mountain (the speak she used was taken from a book on the Alps), and, anyway, she loved to read. The huge work was organized in sections. The first section introduces all the major motifs; after that, each motif gets a section to itself, with some overlapping. The work gathers complexity as it goes along. The house, the tree, the mountain, the line and color sequences, the geometric shapes, the many different techniques of drawing and painting—all these begin to work with one another in the continuity of the whole, which culminates in a 126-plate ocean sequence that employs fifty-four shades of blue. Bartlett never saw the entire painting together until it was installed in Paula Cooper’s gallery; her loft could accommodate only a third of the plates at a time. Sometimes it struck her as the worst idea she had ever had. When it was nearly complete, she still had not decided on a title. An English friend, the architect music; he suggested calling “Rhapsody,” and that appealed to Bartlett’s self-deprecating sense of humor. “It was so awful I liked it,” she said. “The word implied something bombastic and overambitious, which seemed accurate enough.”

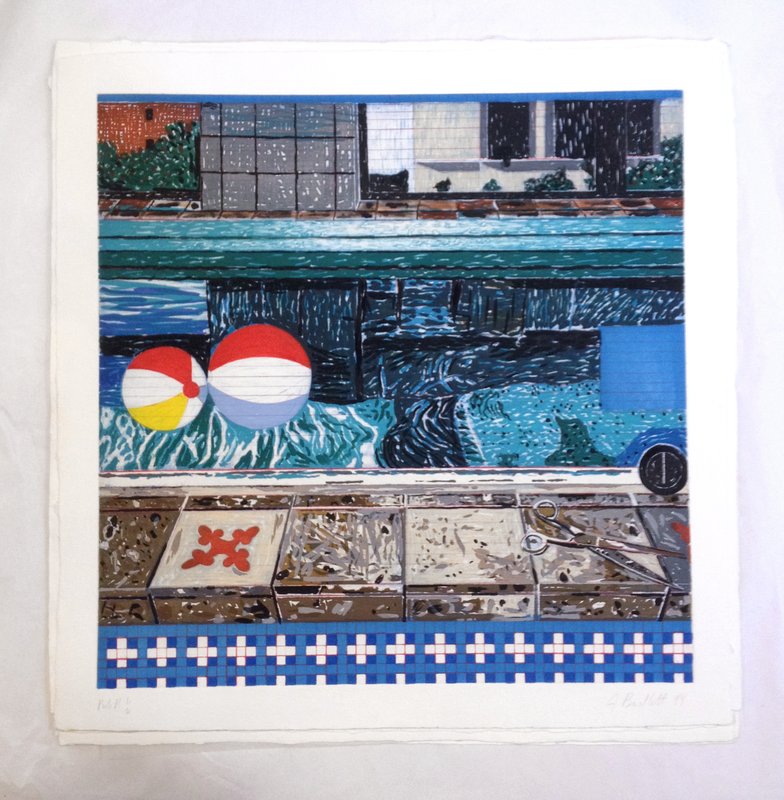

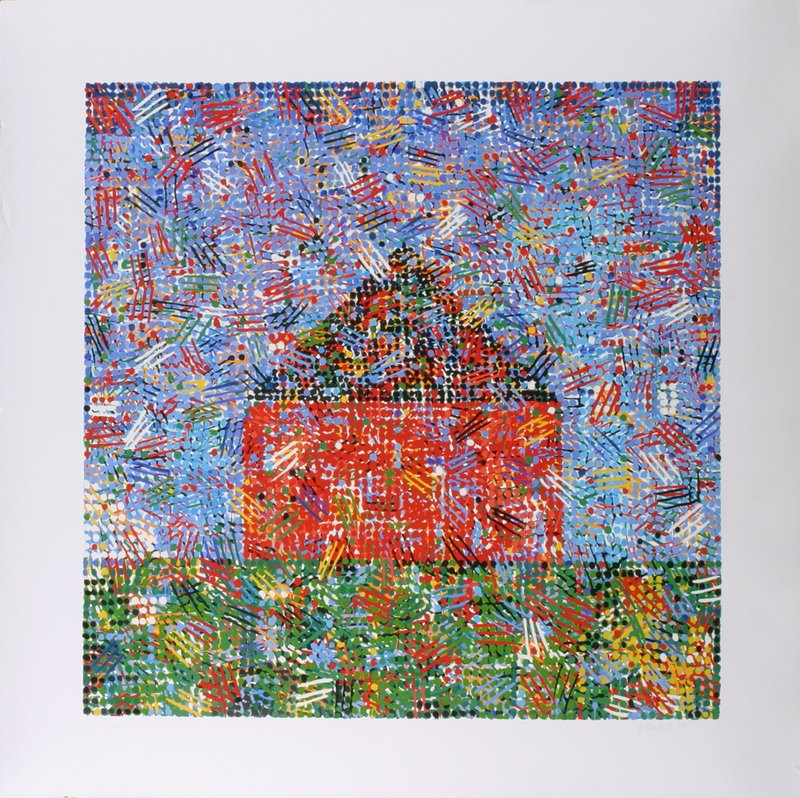

House, Dots, Hatches

(1999) is available on Artspace for $5,500

House, Dots, Hatches

(1999) is available on Artspace for $5,500

It took a week to install the nine hundred and 88 square plates at Paula Cooper’s. Each plate was nailed to the wall, in most cases separated from those around it by exactly one inch on all sides. Although Bartlett had never plotted the measurements of the complete work, it filled the available wall space of the gallery with almost mathematical precision. Word of the piece had been going around SoHo, and the gallery was crowded throughout the opening day, a Saturday in min-May of 1976. Many visitors commented on the painting’s strong narrative quality; unlike virtually all other contemporary painting, it was a work that you “read,” from left to right, and in which you could easily become so absorbed that you lost your sense of time. Although “Rhapsody” was clearly an art-world “event,” nobody was quite prepared for the lead article that appeared in the Arts and Leisure section of the next day’s Times , in which John Russell, the paper’s art critic, described it as “the most ambitious single work of art that has come my way since I started to live in New York,” a work that enlarges “our notions of time, and of memory, and of change, and of painting itself.” Russell’s glowing review was an art-world event in itself, and the repercussions were large and immediate.

The gallery was closed on Sunday and Monday, but on Tuesday there was an even larger influx of visitors. At some point during that frantic morning, Paula Cooper took a telephone call from a man she did not know, who said his name was Sidney Singer. He wanted to know whether the work was still “available.” Paula Cooper said that it was, and he told her to hold it for him—he would be there in 45 minutes. Although Bartlett had decided that “Rhapsody” should not be broken up, she had never really thought it could be sold intact; if anybody wanted to buy a section of it, she planned to repaint that section. On that Tuesday, however, Sidney Singer, a relatively new collector, who lived in Westchester, arrived, within the promised 45 minutes and bought the complete work, for what seemed at that time the astronomical sum of 45,000 dollars. Paula Cooper persuaded him not to take possession of “Rhapsody” until it had been exhibited in a number of museums around the country—showings that gave an added boost to Bartlett’s suddenly soaring reputation.

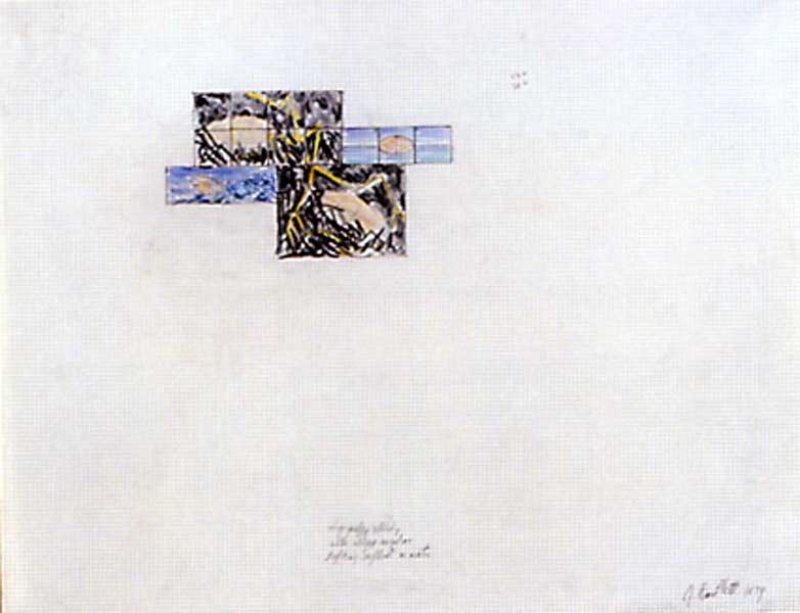

Untitled

(1997), a unique work on paper, is available on Artspace for $5,000

Untitled

(1997), a unique work on paper, is available on Artspace for $5,000

Bartlett’s life did not change dramatically as a result. She paid off a lot of accumulated debts, bought some clothes, and kept right on painting. She also continued to teach at Visual Arts and to write her autobiographical novel. Nevertheless, something very big had happened to her. She had come into her own estate as an artist, and it had turned out to be a rather grand and impressive one. She had gained the confidence to trust her inclinations, which were neither Minimal nor Conceptual, and her work since “Rhapsody” has been a direct reflection of her unencumbered personality as an artist—lavish in scale, decorative, inclusive to the point of being omnivorous, frequently mocking or self-mocking, wildly eclectic, and startlingly ambitious. She is a little like Robert Rauschenberg in her willingness to risk failure at every turn. Her mistakes are all made out in the open, and as often as not they are turned into assets. She said to me one day, “I’ve developed an infinite capacity for work and none for reflection.”

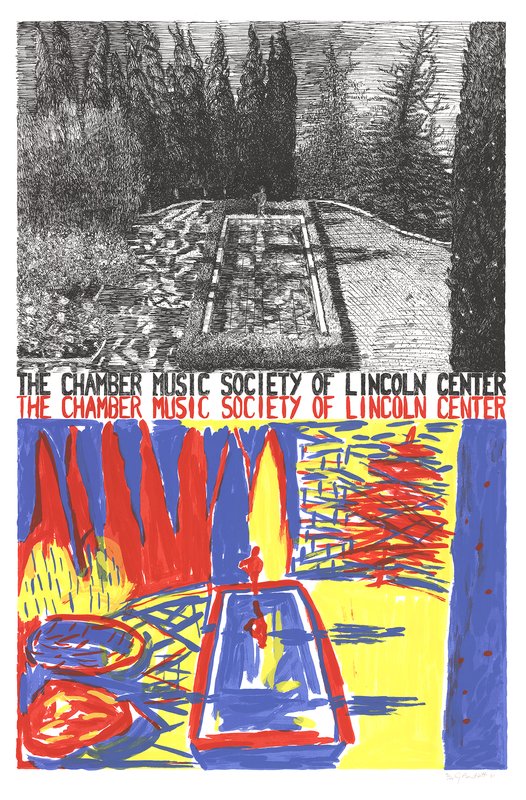

Chamber Music of Lincoln Center

(1981) is available on Artspace for $1,800

Chamber Music of Lincoln Center

(1981) is available on Artspace for $1,800

The series of “house paintings” that followed “Rhapsody”—renderings of the same rudimentary house image—expanded her repertory of painting styles. Impressionism, Expressionism, Neo-Realism, Rayonism, Van Gogh, Matisse, Mondrian, Pollock—sometimes the entire history of modern art seemed to be making a guest appearance in her work, without quite upstaging the host. Bartlett was creating a style out of borrowed styles (and doing so long before the current fad for “appropriation”). Her new house paintings were really portraits of people. Their titles came from addresses of people she knew well (one was a list of the places where she herself had lived), and most of them had some abstract visual reference to a particular person. In “White Street” (Elizabeth Murray’s New York address), she used all 25 of the Testors colors, to suggest the kind of “contained chaos” that she associated with her friend. The most impressive painting in this series was named for Elvis Presley’s Graceland Mansion, because Presley, a childhood idol of Bartlett’s, died while she was painting it. “Graceland Mansion” is really five paintings hung in a horizontal sequence, showing the same symbolic house image from five different angles, at five different times of day (its shadow falling to the left or to the right), in five different painting styles. Bartlett’s most famous print is derived from this painting. Also called “Graceland Mansion,” and published in an edition of forty, it is really five prints, each done in a separate technique: drypoint, aquatint, silk screen, woodcut, and lithography.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Critic Calvin Tomkins on Vija Celmins (And Her Cat)

Collecting Strategies: Invest in These 6 Artists Who Had Solo Shows at MoMA PS1

In Honor of Hillary Clinton, Here Are 10 Women Artists Who Made History