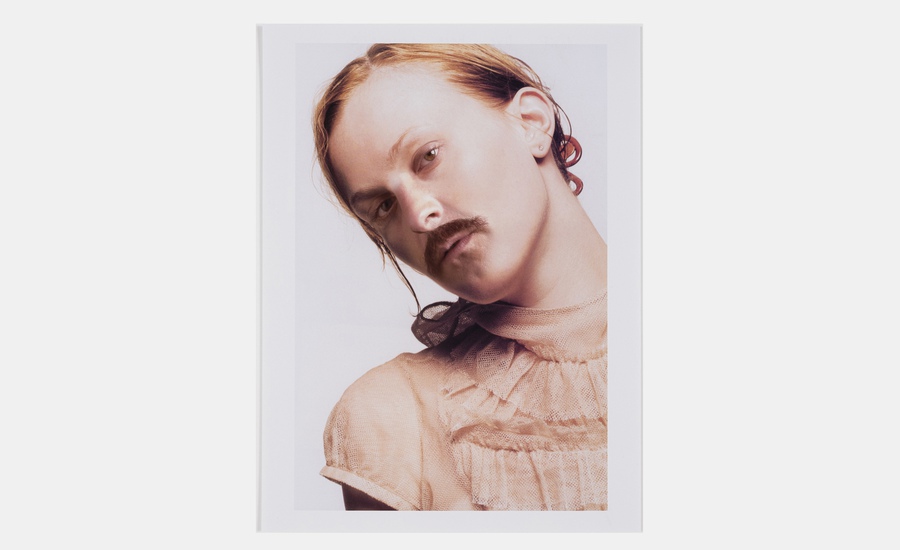

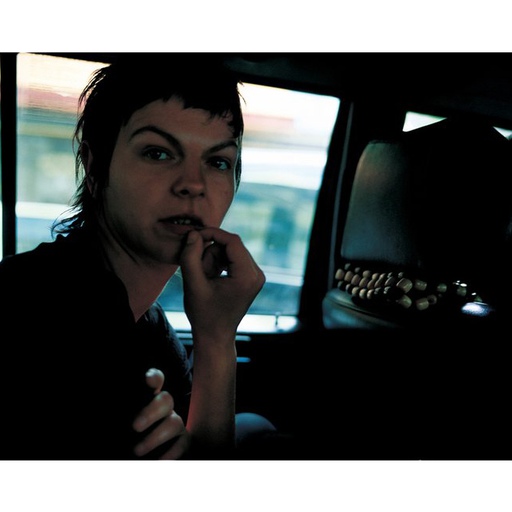

What is the point of pictures? The photos that the Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone uses as the source material for his series, I Don’t Live Here Anymore , have a clear purpose. They are images of glamorous women (models mainly), photographed and published in fashion magazines during the mid-1990s, when Rondinone’s career was truly starting to take off. Readers of the style press from this time may even recognise a few of the artist’s sources.

In their original form, these pictures were beautiful and aspirational; at some level, they were meant to encourage people to buy clothes. They were not hard to admire or understand even – that is, until Rondinone went to work on them.

Ugo Rondinone

The artist didn’t leave these sharp, stylish images untouched; instead he superimposed his own (clearly masculine) features onto the faces of the women in these photos. Both timeless and prescient, I Don’t Live Here Anymore subverts the pictures with that superimposition, resulting in a fluid mix of masculinity and femininity, familiarity and ambiguity.

Catch sight of the original photos on a newsstand and you probably wouldn’t feel the need to look at them again. But see Rondinone's reworking of them, and you can’t help but return to the image.

UGI RONDINONE - I Don’t Live Here Anymore (1995/2022)

One of those images, I Don’t Live Here Anymore (1995/2022) - originally created in 1995 - is now available as a limited edition for the first time ever . The work is part of the new Collectors’ Edition of Rondinone’s Contemporary Artist Series book. Printed on Fuji Crystal Archive paper, it measures 12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm), and is limited to just 30 prints (as well as 6 APs and 1 PP), each signed and numbered by the artist on a label on the reverse .

Commenting on the series from which the new edition is drawn, Rondinone says: "My interest lies in the human condition and its place in the world. I see the world as a mysterious place where appearances are deceptive and ultimate reality is rarely perceived. A world where each individual creates its own time and space. It’s a paradox. On one side we experience time and space as reliable and predictable entities, where time and space present us with a deceptive form of reality. But the inner life of time and space is labyrinthine and perilous.”

The limited edition I Don't Live Here Anymore with its Phaidon monograph

Years before trans rights were a household issue, I Don’t Live Here Anymore seemed to blur the gender divide, without forcing the artist to pick a side. Though Rondinone is wearing make-up in the images, he hasn’t actually dressed as a woman. Instead, he’s simply put his face in the picture; and anyway, as the title itself explains, Rondinone doesn’t Live Here Anymore.

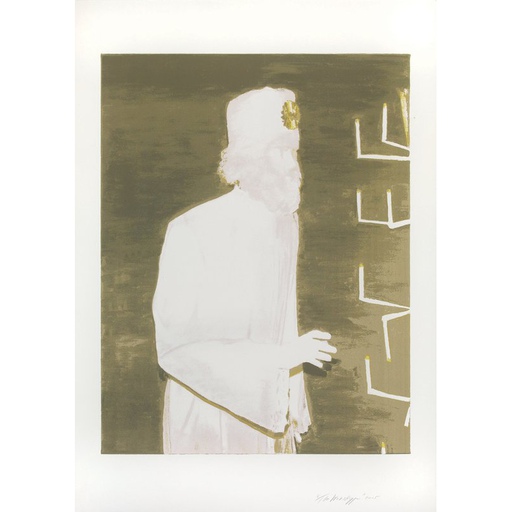

The ambiguity was further amplified when Rondinone showed these works. They were presented at the artist’s first institutional exhibition, in 1995 at Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva, where they were hung alongside his airbrushed circular ‘Rothko in the round’-style sun paintings.

The abstract, machine-like perfection of these pretty, circular paintings, sat oddly with the jarring, gender splicing of their photographic wallmates, but as curator and critic Erik Verhagen puts it in the new Phaidon Contemporary Artists Series book , “Rondinone is striving, not only for a perfect balancing of motifs, but also of formal qualities. The blur of the sun paintings finds its echo in the blurred gender identity of the photos.”

Rather than striving to become an artist known for one, easily recognised style of work, the curator Bob Nickas has described Rondinone’s ouvre is, as an “expanded field with many centres”. Erik Verhagen says Rondinone's "art isn’t open to a single interpretation, other than that the human experience is changeable and via the image of his transvestite self-portraits, the artist seems in effect to be simultaneously revealing himself while retracting; providing a key while concealing the lock.”

On first impression, an uninitiated viewer may not think to put these photos and paintings together, in an exhibition, in a private collection, or in a single artist’s body of work; but Rondinone’s canon – just like our own lives – cannot be reduced to a few cliches; instead it contains multitudes.

For more information on how you can get a copy of the new edition go here .