When the influential Museum of Modern Art curator Laura Hoptman claims that she’s “a painting person,” it's no joke. A veteran organizer of cutting-edge exhibitions, she built her career in part through her insistence on championing the medium, even—or perhaps especially—through its perennial periods of unpopularity and critical disdain. This has earned her both accolades and scorn, but her track record of introducing vital contemporary painters to American audiences largely speaks for itself.

From her start at the Bronx Museum of the Arts in the late 1980s to her assistant curator position at MoMA—where from 1995 to 2001 she oversaw the first American solo museum exhibitions for pathbreaking artists like Luc Tuymans and John Currin —Hoptman has remained steadfast in her belief that good paintings will always be relevant.

After her first stint at the Modern, she decamped from her hometown of New York for Pittsburg’s Carnegie Museum of Art to head up its contemporary art department, where she organized the 2004-2005 Carnegie International . The departure was short-lived, however, ending when Hoptman returned to the city as a senior curator at the New Museum , bringing in works by painters like Elizabeth Peyton , George Condo , and Tomma Abts while also organizing seminal exhibitions including “Unmonumental: The Object in the 21 st Century”—the influential show of provisional-looking sculpture that famously included a lot of paint—and “Younger than Jesus,” the first iteration of the museum’s Triennial.

These successes launched Hoptman back to MoMA in 2010 as curator of contemporary art in its painting and sculpture department, and since then her landmark show has been “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World,” the 2014 conversation-starter billed as the first contemporary painting survey at the institution in some 30 years, featuring 17 contemporary abstract painters—including Mark Grotjahn , Kerstin Brätsch , and Mary Weatherford —who notably remix the techniques of painters from previous eras. The show proved a magnet for critics suspicious of certain trends in new painting, and his “ahistorical free-for-all” (as the museum called it) was harshly dissected, with many commentators arguing that its works flew too close to the much-reviled trend of “ Zombie Formalism ,” whose practitioners often describe their history-pilfering process in similar terms.

Today, Hoptman remains firm that the artists she included, and still supports, are vital to the conversation around contemporary painting. Here, in the latest of our interviews surrounding Phaidon 's Vitamin P3 compendium of recent painting (for which Hoptman served as a nominator), Artspace 's Dylan Kerr spoke to the curator for a fascinating glimpse behind the scenes of her work, discussing the staying power (or lack thereof) of the “Zombies,” the strange and sometimes strained relationship between institutions and the art market, and why a good curator focuses on needs, not trends.

The medium of painting has reasserted itself as a viable and relevant art form in recent years. However, this re-centering has also come with its share of skeptics, especially when it comes to the so-called “Zombie Formalism” of the past few years. What do you make of these criticisms?

I think if you had read Texte Zur Kunst throughout that period of time—you probably did—you know that there were always these skeptics. I think the skeptics, at least over the past five years or so, were proven right with regard to the artists who are making abstract paintings that are perfect for the way they are consumed: They make a lot of them, there’s a green one and a blue one and a pink one, and you can collect them all like toys in a Cracker Jack box, which is what they’re all about. The sameness, the repetition, is extremely important, because you want a piece that’s instantly recognizable as being from one of these painters.

There’s this group of artists—mostly from the United States, Germany, and the U.K.—who, it seems to me, just said, “This isn’t so hard.” When, actually, it really is hard. To make a good abstract painting is really, really, really hard. What’s not hard is to make an object that looks okay and is salable. That’s not hard at all! [Laughs.]

As someone whose job is at least in part to make these distinctions, how can you tell the difference between a genuinely good abstract painting versus, as you say, something that is very salable—something that simply looks like an abstract painting?

If there’s any way that a viewer can discern investment—I don’t mean money, but investment—that’s always a good thing. It could be time, and a lot of people think time is important. But I believe in belief. I believe that if people think they’re doing something for a purpose, then it’s worth looking at. Whether I like it or not, someone will like it at some point.

Of course it’s also important to be ironic, to problematize this notion of belief, like Wade Guyton does. Do you remember those fire paintings he did? When one went for so much money, he whipped off five or six more on his machine and then sold them. I have total respect for that, because he knows what he’s doing and he knows where he’s coming from. He understands the problems of presentation, but also reception. He gets it. But there are people who don’t, people who are just doing it in a way that could be considered slightly cynical. If you’re nice, you say “cynical.” If you’re not nice, you say “stupid.”

There’s nothing wrong with being stupid. There’s that old phrase, “stupid as a painter.” I’m all for being stupid as a painter. But I’m not for being a jackass about it. And the worst part about it is that we old folk can see that these people were jackasses ready to crash and burn. Given who they were trucking with, the people who were buying and selling their work like it was Bitcoin—you’d have to be stupid to continue along.

There aren't that many of them, even if I’m making them sound like a huge group. But there are some of these younger artists who say, “I can make money as an artist. This is my profession. I can hire people, and I can go in at 9 o’clock and punch the time clock and make 12 of them, and come out, and go home.” That attitude, that way of looking at art, is mistaken. It is wrong.

This has been my belief system since before I began: I want be with the believers. I don’t want to be with the cynics, or the jackasses. I do believe, and I hope that history will prove me right. I hope I don’t sound arrogant, but with my show “The Forever Now” I was very careful not to include artists who might be in this as a profession, who might not end up being artists 10 years into the future. I was trying to keep the people who were doing it for real.

When we eventually start looking back on and reevaluating these past five or so years of art, do you think we’ll come to see these “non-believer” paintings fondly, or at least with a smile?

The ones done badly or cynically or mistakenly? Well, if you ask me, I would say no. Other people might say yes, I don’t know. Would you think that after the demise of Op Art , which was considered easy art, that we would be at all interested in Victor Vasarely ? Well, now people looking again at Vasarely, and it looks OK. A lot of things come back.

That said, I also think that there probably is a divide between real and bogus, and I don’t know who’s going to make that decision going forward. I believe, in my heart, that the ones that are bogus probably won’t be on the walls of the museum. They might be on the walls of people’s houses, but not the museum.

Installation view of "The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (December 14, 2014-April 5, 2015). Photo by John Wronn © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

Installation view of "The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (December 14, 2014-April 5, 2015). Photo by John Wronn © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

Let’s turn to your 2014 exhibition “The Forever Now,” which you’ve mentioned already. Almost every article on the show highlights the fact that it was the first contemporary painting show at MoMA for many years. What was the impetus behind putting a show like that on?

That show that got creamed by basically everybody. However, I stand behind every single artist in that show. The idea for that show was that these were artists who were trying to re-assimilate other already-known properties of painting, other already-known connections, but the real curatorial connection there was that everybody touched the canvas.

It was the first contemporary painting show for many years, and that’s reason enough, right? Of course, painting was in the discussion. This kind of abstract painting was around, and it was mostly expressionistic work—I don’t know if anybody really noticed that. But I was also interested in this—I keep using the word “belief,” which sounds so religious—this straightforward interaction with the canvas. Everybody touched the canvas. To me, that said that there was a certain interest in the history of painting as an authentic vehicle for making art.

We knew that it was interesting. It was also timely, because there were a lot of artists making paintings, and all of a sudden there was this appetite in the public for painting as well. Also, I’m a painting person, so I wanted to do a painting show. It’s important to know that we all knew that a lot of people were not going to like it. [Laughs.] Because that’s also the history of painting shows at MoMA: some people like them, and some people don’t.

Totally—you can see that opposition going all the way back to the controversial modernist exhibitions that made up the museum’s first shows in the 1930s.

Some of those were really great. Dorothy Miller—what a great curator. The thing is, in the late ‘40s and ‘50s she did these exhibitions with some regularity—an individual show wasn’t the definitive painting show just because one hadn’t happened in forever. They were put on once every two years for a while, then over a five-year period, so there was some kind of drumbeat, some time to adjust. Plus, you can include a lot more artists.

I didn’t have any figurative painters in my show, for instance. There are tons of figurative painters working today, and I would love to have included them, but I had 5,000 square feet. It doens't mean that I'm going to stop MoMA from doing another contemporary painting show for 30 years, although any of my colleagues that decide to do it, I would salute them. [Laughs.] It’s not fun to get raked over the coals. As I said, some of it was expected, but curators don’t necessarily want to make exhibitions that they know the art community is going to have a big fight about. I hope it encourages somebody to do another one here soon. I’m going to push for it. Do it till we get it right!

How do you deal with the criticism of the show?

You get schooled, number one. Obviously, I’m not the only one who is right. My art historian friends loved the show to a one, which actually schooled me in that way. That’s what I am—I’m an art historian, and perhaps I think that that part of it was strong. I know what I was trying to argue, and I thought it was provocative. I guess what I’m saying is I believe in what I did, and the criticism and the fighting didn’t stop me from believing in it. I knew what I was doing and I stand by it.

I also think it is healthy to have a fight and to spawn other exhibitions, which as I remember did happen. In little commercial galleries, people were trying painting shows. None of them were very good. I felt sad. I really wanted to walk into one that was really awesome, that would bury the one that was at MoMA, but I didn’t see that. Because it’s tough!

There was one interesting one more than a year later, a little figurative painting show at the Whitney. I thought that was interesting and people were talking about it a lot. I didn’t love two out of the four painters, but I thought that was great. It added to the discussion in an important way.

The other thing was criticism from the collectors, who said, “You didn’t discover anyone.” It wasn’t like I was focusing on unknown artists. They are legit, and I stand by them. Doing a contemporary painting show at the Museum of Modern Art is an interesting exercise nowadays, in second decade of the 2000s, because we are conferring value onto what we put on the wall. I might as well say it—I felt uncomfortable crowning kings in this particular show, so it was an idea-driven show with artists that I knew and trusted. I don’t have to prove that they’re good artists. They know they’re good artists, and almost all of them have a track record a mile long.

That was the strategy—maybe not the right strategy. I’m sure I made a lot of mistakes. But there were always reasons to do that. I think MoMA is not the place where you go to discover new—AKA “cheap”—artists. These collectors are looking for artists they can get in on the ground floor with. MoMA is where you learn what the important bits of the discussion are about, and maybe a little art history. Although, you never know: if you look back at Dorothy Miller’s shows, the artists she put in her exhibitions in the late '40s and early '50s included most, if not all, of the great Abstract Expressionists .

Installation view of "The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (December 14, 2014-April 5, 2015). Photo by John Wronn © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

Installation view of "The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (December 14, 2014-April 5, 2015). Photo by John Wronn © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

I wonder if we can talk a bit more about something you just mentioned, which is that in the present day museum curators have an interesting relationship with the art market itself. You were saying that museum shows can become a “what to buy” list for a certain level of collector. Is that something that’s changed since you started work in the museum world?

You know what? The answer is actually no, because the market was already the market when I started in the mid-1990s. In a weird way, we don’t have a relationship to the market. We have the pleasure to use works of art in exhibitions and acquire works of art without being too concerned with the cost—though money is certainly an issue, and it is very expensive. Whether or not they’re popular in the art market really doesn’t have that much weight. I’ve been at this for a long time, and I can’t tell you how many times that I have been cited as using a “market artist from X gallery” when I was working with the artist before the gallery was. It’s so frustrating. The gallery system often sees the artists that MoMA is working with and then picks them up. Nobody ever gets the chronology right!

That’s exactly the relationship I was suggesting, that the museum posits people as important artists, and the market follows that as a recommendation.

Sometimes. No, not sometimes—often. Of course, with places like the Museum of Modern Art, we choose artists that we can use with our curatorial concepts. Be that as it may, we are one of the greatest museums in the world, and no matter how much criticism we get, we are enormously respected. That means that if you have your work in the Museum of Modern Art, it confers some value, though I think a lot less than it used to. That’s not just at MoMA, but anywhere. When I worked at the New Museum, we had this discussion too. It seems so upside down. Say I show a Mark Grotjahn at the New Museum—is that really going to up its value?

I’m interested in the idea that market prices and museum recognition are actually not as directly connected as one might think. Why do you think that is? Is it that the market has become such a strong force that it doesn’t need institutional validation?

Exactly. [Laughs.] Well put. I think that, just like there are lots of art worlds, there are lots of art markets. There are certain parts of the art market that, of course, don’t need institutional validation. They’re on their own, they do their own thing. Their validation is how many of pieces they can sell, and for how much money. Although people who are older than me chide me and say that this is something that happened all the time, it seems new to me that, in the past five years or so, economic value is conferred on a work of art because of its auction price, and only because of its auction price.

It’s almost a tautology—they’re valuable because they’re valuable.

Well, yeah. And that means that smart people can create value by making their prices higher, or by buying a lot, or—I’m not an economist—by making something scarcer. There are lots of ways you can work within the art economy to make it happen. [Laughs] It’s not incredibly easy, but you know what I mean. I guess that was a bit of a rude awakening for me, that that was the main reason why something was valuable and good. I have a lot of favorite artists who have no value, that’s for sure.

Are there a few names that spring to mind?

There’s one who was my very good friend, somebody whose work I showed when I worked at the Bronx Museum, who died of cancer at the age of 55 in 2013. His name is Billy Lynch. He was my husband’s close friend, and we always thought he was a genius painter. I still do. Just beautiful, wonderful work. Billy went to Cooper Union in the ‘80s, but he could never get any attention. He had problems with mental illness, and then he got cancer and died. He did have a show—my husband curated it, actually—in 2014 at White Columns, which was the first legit New York show he had ever had. Bill Lynch—look him up.

What are the currents in contemporary painting that have you the most excited when you’re out exploring now?

Good question, good question. Let me think. I think that Laura Owens might be the caposcuola—although David Salle has been doing it too—for the way people are assimilating digital languages into painting. We’re two or three generations—in the sense of a copy, not people's age—past Wade Guyton’s digital paintings, and we’re getting all kinds of different ways people are using the languages of digital painting. Kerstin Brätsch is a good example. This is a painter qua painter, although she works in all kinds of mediums, but the way that she uses digital images as the subject for her hand paintings just slays me. She’s a wonderful artist.

Installation view of "The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (December 14, 2014-April 5, 2015). Photo by John Wronn © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

Installation view of "The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (December 14, 2014-April 5, 2015). Photo by John Wronn © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

You have a reputation as someone with a really prescient eye, who can find the great artists before they make their big break and then put them in the museums. What do you look for in new artworks?

I’ve always wanted to be around artists. I’m a fan. It’s the artists who have told me who is interesting for pretty much my entire career. Elizabeth Peyton told me about Kai Althoff , and my husband told me about Elizabeth Peyton. Elizabeth introduced me to Laura Owens, too—I have to give her that. Gabriel Orozco told me about Luc Tuymans. Chris Ofili told me about Tomma Abts. Mark Grotjahn told me about Mary Weatherford. Artists are my secret weapon, which I happily tell to everybody that I know.

After that, I don’t know. I don’t want to call it intuition or something—I don’t know if I believe that—but I do the best I can to curate on the basis of need. That’s something that Holly Block told me—she’s the director of the Bronx Museum now, but was a curator back in the ‘80s at my first job. She was talking about the need for the artist to live, to work, to have money. Now, I’ve taken that and twisted it so that for me, I try to choose the artists who are relevant, who we need now in the discussion.

Tomma Abts is a perfect example. I really felt like we needed Tomma to stir up the painting discussion that was happening in the late 1990s and the early 2000s. We needed her to up the ante with her work—that ugly, wonderful abstraction. Paintings that only a mother could love. Of course, now all think they’re beautiful.

It almost sounds like an instrumental way of using of the artist. There’s tons of art being made, but what you’re interested in is, as you said, the art that’s necessary for pushing the conversation forward.

I think so. I mean, that’s my job. I’m not buying art. I work in a big museum that 5,000 people go to per day. It’s not so easy to get right, by the way. Sometimes you don’t. And not getting it right doesn’t mean bad reviews from your colleagues in the art world—it means nobody goes to the show and it’s not in the discussion. That’s bad.

RELATED ARTICLES:

RELATED ARTICLES:

How to Buy an Artwork You'll Love on Artspace (or Anywhere Else, Really)

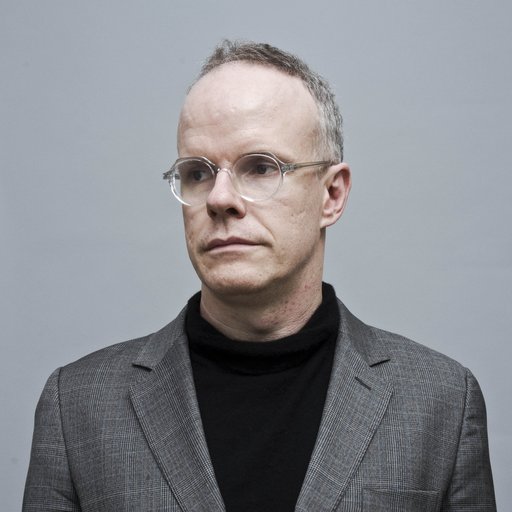

Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist On What Makes Painting An "Urgent" Medium Today