The eminent German curator Kasper König has had an extraordinary career in Europe, organizing his first show—a survey of Claes Oldenburg's work—at the age of 23, working on Pontus Hultèn's seminal Warhol retrospective at the Moderna Museet at 25, and going on to curate dozens of major exhibitions, found Frankfurt's esteemed Portikus kunsthalle, and hold professorships at the Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf and the Städelschule. In his native country, he is known as an exceptionally independent-minded figure who refuses to bend to political pressures in organizing his shows.

Yet today König finds himself at the center of tumultuous world events as the organizer of Manifesta, the international exhibition that this year has been sited in the historic Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. Curating under the eyes of the authorities in an increasingly politically restrictive and dangerously expansionist Russia, he has been exposed to protests from artists and accusations that Manifesta is insufficiently critical of the regime.

With the exhibition now open after a fraught run-up—at one point it looked like the show would be canceled due to lack of payment for Manifesta's Russian staffers—and set to continue through October, audiences now have a chance to see König's handiwork for themselves. We spoke to the curator about what the experience of putting together the show was like, why there is no viable art community in Russia anymore, and where gestures of political provocation and critical engagement with the government were able to slip through into the Hermitage's galleries.

Today you find yourself at the center of world events, as the organizer of Manifesta in an increasingly politically restrictive and dangerously expansionist Russia, with a show that has become placed in a context you could not have foreseen. How did you find yourself here?

When I was asked to make a proposal, I immediately said, "Yes, I am very interested," because I had never been to Russia. I knew some about the Hermitage and its history, and I wanted the chance to look behind the scenes—to look behind the façade. I was one of three people being asked, and they did not tell me who the other two colleagues were, only that they had a background in the Hermitage and with running a museum. So I made a proposal with a young American colleague, Emily Evans, who was an intern at the Museum Ludwig and is a specialist in Russian constructivism and photography, because they wanted me to write the proposal in English, and I wanted to have a kind of sparring partner of a young generation.

When I finally signed the contract, which took me two and a half months to define, it became quite clear that I was going to work in a society that is not a civil society, that doesn't have a clear structure, and that is very precarious. However I did not know how precarious it was going to be. Shortly after I signed the contract, this very ridiculous anti-gay-propaganda law was passed, then the annexation of Crimea started, and then the country went into a kind of military momentum of annexing a large part of the Ukraine.

It became more and more complex, but by then I was already quite far ahead, and most of the artists had visited for a week or more, and it became quite clear that it was very important to go on and make the exhibition a good exhibition of good art, and not try to deal with the daily political issues. Because the Hermitage is celebrating its 250th birthday, it’s a very complex institution with a very complex history. It saw three revolutions, and it was founded by Catherine the Great, who was a figure of enlightenment but became the opposite, turning into a kind of Napoleon. I thought that history deserved to be given its due.

Once the parameters and context for the show became apparent, what was your curatorial vision for the show?

The parameters were quite clearly to present contemporary art within the last 25 years that I felt would be fruitful, necessary, and understood. Some of my proposals didn't work out because either the space wasn't there, or there wasn't a sympathy for it, or too much would have needed to be explained. When I made my proposal I included a list of 150 artists in alphabetic order, of which I said one third of them would most likely would be invited, and for each of them I gave my reasoning, sometimes because they had been present in previous Manifestas. Quite a lot of them are from Eastern or Central Europe, which I felt was essential in relationship to what the museum is about.

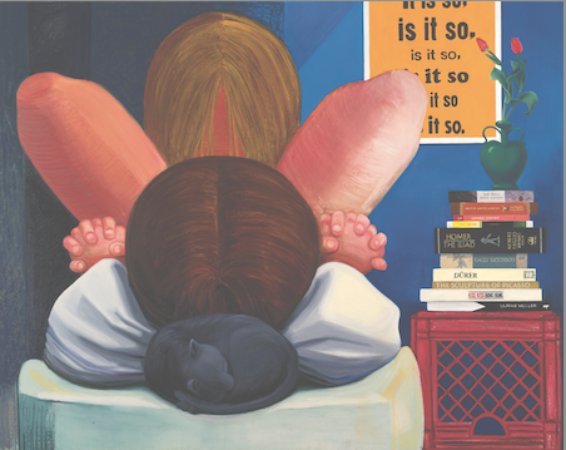

Then, for example, something I proposed was to take all of the work of Matisse from their three galleries and bring them into the new building, and instead present three women painters who all deal with the body, like Matisse, but not as a subject, as an object. They are Nicole Eisenman, Marlene Dumas, Maria Lassnig, who died in the meantime at age 94, and now she has a big room in the new building that is called the "Room of Honor."

Nicole Eisenman's It Is So (2014)

Nicole Eisenman's It Is So (2014)

You worked with Mikhail Piotrovsky, the director of the Hermitage, on the show, and he has said that the goal of the show was not to breed political provocation but "to create a wonderful artistic event" that put art "back in the ivory tower." In fact, he has said that he was afraid he could "be sacked in one minute" if he touched politically provocative work. What was it like working with him?

In the case of the ivory tower comment, which sounds regressive, he was misunderstood, because he said clearly at a conference in London that the ivory tower was there to defend the territory of art. So I think he’s a fantastically open-spirited man, he’s an orientalist, and he’s a great diplomat. Basically, he’s the most significant figure of the exhibition. He made it all possible, but he never defended it in specifics. He just made it possible, that’s all.

You yourself said that you didn't want to show anything that would "constitute a cheap act of provocation" considering that you had been given "major opportunities" and that "the possibilities for this exhibition are very rich." What did you see as these opportunities and possibilities of having a show in Russia at this present time?

Basically the opportunity was to not try to be original, not try to be inventive, but just to do what seems to be necessary from an aesthetic point of view. In a museum like the Hermitage, quality is essential—everything has to be the very best. This doesn't mean that it has to be the hundred best or most expensive artists, but they all have to be very legitimate artists, so that if they're challenged, they gave their best, and that’s what it’s about. It’s a very different set of artists than the one which most people would agree on.

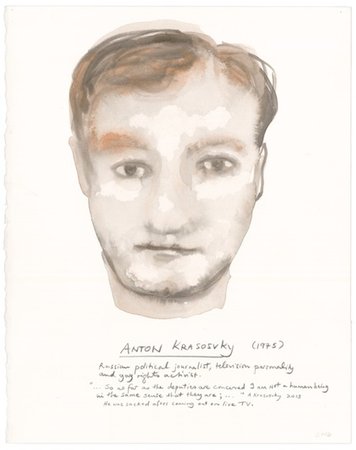

Marlene Dumas's Anton Krasovsky (2014)

Marlene Dumas's Anton Krasovsky (2014)

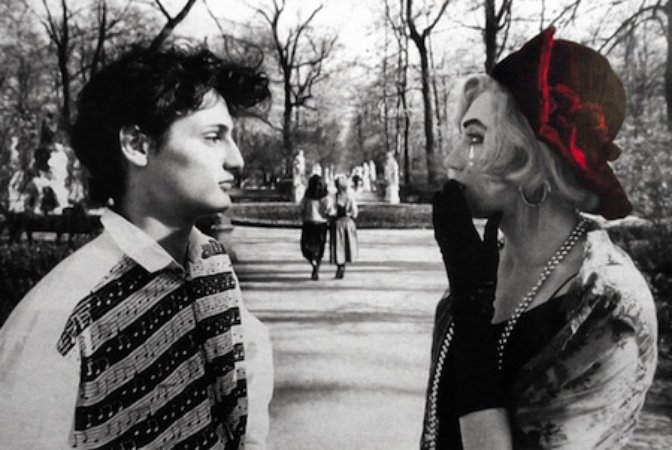

After the announcement of the show's destination last August, there was an immediate backlash to the choice of location in light of the notorious anti-gay law that Putin had signed shortly before. You called the law "disgusting," and in the show you have included a range of strongly anti-homophobic works, such as pieces by Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, the cross-dressing Russian artist who was a gay rights icon until his untimely death last March at 43. There is also a Nicole Eisenman painting that appears to depict two women having sex. Wolfgang Tillmans says his two-gallery installation of somewhat suggestive photographs was "probably the gayest show I have done." Marlene Dumas contributed 16 watercolor portraits of gay men, entitled "Great Men." What was your curatorial intent with these pieces?

I think it has more to do with a kind of generational momentum. You see, I grew up in West Germany after the end of the Second World War in the years when it became clear that it was the end of the Nazi time, and when children were asking their parents what happened during the war. There was a necessity to deal with the country's own traumatic collective situation, and visual art was an essential part of both looking back into the past and looking into the future.

Right now art has become so preoccupied by the fruits of success and the market and so on, and I think it's important to turn back to these basic questions, to go back to what art means to somebody. It was a real shock when this antigay law was passed—it was a sort of populist situation that was eminently inhumane and fascistic. And then you have all this argumentation that the Maidan in the Ukraine is a kind of Nazi-fascist territory because a lot of them collaborated with the Nazis, who promised to make them autonomous, and so on. So the political situation is so complicated that art is not necessarily going to be able to change the world, but at least it can show things being as complex as they are, and not in a stupid way of simplifying it.

Right now it looks like there is a good audience of young people who are really taking the show very seriously. Students from all over have gone there and spent a few days with the show. It's really a process, and at the end of the show I think it will be a pretty good exhibition because there is such a kind of emotional resistance towards it. It’s a huge institution, so it’s understandable that it was like a shock. But it was not our intention to make a shock.

Wolfgang Tillmans's Yet Untitled, 13 (2012)

Wolfgang Tillmans's Yet Untitled, 13 (2012)

Then, after Russia annexed the Crimea, there were calls for a boycott. A few artists dropped out, including Pawel Althamer and Artur Zmievsky, who was the co-curator of the Berlin Biennale with Joanna Warsza, who is overseeing Manifesta's public programs this year. You called the boycott misguided. Why?

It is a complicated situation. I had invited Pawel Althamer and Pavel wanted Artur Zmievsky to participate because he had a project dealing with monumental sculpture in a socialist context, so I invited him too. And then Artur insisted that Pawel should boycott the exhibition. And I said to him, "Look this is something for Pawel to decide himself. If you are the spokesman for Pawel than he needs to tell me that, because I’ve known him for 25 years and we have worked together a lot. But then, finally, Pawel resigned because Arto pushed him so hard.

I said okay. I honor it very much if somebody boycotts something, but a boycott should also cost you something. If you boycotted then you make a commitment. This is very honorable. But don’t push other artists. Don’t get into a kind of idealogical political in-fight. So I’ve had a couple of situations where I had to say, "Look that’s fine, you are in or you are out. But you are not in to be out, and then out to be in. Let’s focus on the art and on whatever it means to exhibit, to make something public, and not to put out on the Internet in the form of a protest but to do it physically in the museum." I understand this is a political opportunity, but not in a daily political sense.

Thomas Hirschhorn standing in front of Abschlag (2014), installed in the Hermitage's General Staff Building

Thomas Hirschhorn standing in front of Abschlag (2014), installed in the Hermitage's General Staff Building

Some of the art in the show seems to read in precisely the context of war, such as Thomas Hirschhorn's Abschlag installation that creates a huge ruin of what appears to be a bombed building in which paintings by Malevich and other Russian utopian painters, borrowed from the Hermitage, can be seen dangling. One would be hard-pressed not to see that as a critique of, or at least commentary on, Russia's martial aggression.

Oh yeah, it’s amazing! He called it a "Potemkin villa," and he is doing this in a psychological setting, dealing with a reality that is being repressed. With the Malevich and and other riches up there, people, "Hey, is that really the original? What does it mean?" Thomas believes in the aura of the authentic work of art, which is very wonderful old-fashioned emotional kind of position. I mean, he calls himself a soldier of art—he’s a real kind of hardcore moralist. He's also making fun of this pompous neoclassical architecture, because his structure looks like something from under Franco's military dictatorship.

So much of the Russian art that becomes known in the West has very strong political stances, from Pussy Riot to Voina to Alexander Brener to the Blue Noses to Erik Bulatov. Was there ever a temptation to include some of that work?

Yeah, but you see Voina is fantastic, but it makes no sense to put their work in a museum because they left on their own. When they painted that prick on the drawbridge outside the former KGB building, they knew what they were doing, and they left Russia the same day. But there are four artists in the exhibition who dealt with with Pussy Riot, including Olivier Mosset, who is a monochrome painter. He has five huge paintings in five colors—including a weird violet, a very aggressive green, red, and yellow—and these colors, which I only realized later on, are the colors of the masks of Pussy Riot.

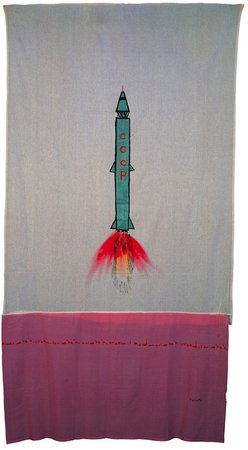

Timur Novikov's Start (Rocket) (1989)

Timur Novikov's Start (Rocket) (1989)

Do you find political artworks to be effective?

I think the most interesting political works I know have been done in a public kind of context, like Erdem Gunduz in Istanbul, who basically just stood there for eight hours in a public square, staring at a picture of Kemal Ataturk, not saying anything, not doing anything. Photos of his performance went all over the world, and he became a symbol of resistance towards the fanatic religious grandeur of Turkey today. Even the Banksy phenomena. Banksy represents a new situation in which the artist is separating himself from the high-art art world and we have to catch up. I tried to lure someone like Banksy to St. Petersburg. You can’t invite somebody like Banksy, but you can say maybe this is an interesting context in which you might appear, and if you have a contact who can help you get a good lawyers. One shouldn't be naïve about these things.

Russian contemporary art is famous for its jarring and arrestingly provocative performances, from Alexander Brenner's defecation in the Hermitage in front of a van Gogh painting to Oleg Kulik's dog pieces. Did you consider this tradition in putting together the show?

Kulik was very important in the first Manifesta, when he did his performance of being a dog in the streets of Rotterdam. Interestingly, Erik van Lieshout, who made a wonderful installation in the Hermitage for the show, saw Brenner when he was 17 years old when Brenner was out there as a dog, naked, surrounded by about 15 to 20 middle-aged Turkish immigrant women who had never seen a naked man on the street. And Erik was fascinated and said that this was really a fantastic dog, and he liked the way the women examined the naked man, not like a man going to a strip-tease joint to pay for it but just completely shocked and interested.

So the presence of Kulik is there in the show, but Kulik himself is not, and he is obviously very upset, but then none of his work of the last 15 years was necessary for me. He’s in the film section quite extensively, however, with historical material.

And then there is the artist Yuri Leiderman, who said he didn't want to be in the film section anymore after Russia got involved in the Ukrains, since he's Ukrainian, even though they are films from 15, 20 years ago. He wrote a manifesto where he declared me to be a collaborator in the way in 1938 the Nazis would collaborate with Chamberlain.

And I said, "Look, this is not only in bad taste, this is stupid." But I was going to shake his hand, because I know him, and he said, "No, I’m not shaking your hand. You are horrible person." And he was going to give me his pamphlet, which was directed against me as a person. I said, "I’m a democrat, I'll pick it up from a pile—I don’t want to be privileged by having it specially handed to me by you."

I had never experienced this kind of thing before. To work with real censorship exists, but it’s not as direct in effect as censoring yourself, and living with a censor within you. So that’s where a man like Piotrovsky comes in, and he’s fantastic.

Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe's hand-colored black-and-white photo Tragic Love (1993)

Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe's hand-colored black-and-white photo Tragic Love (1993)

Manifesta has a history of sparking protests among artists.

Yeah, and what's fantastic is that the first Manifesta dissident was Hans Haacke, who turned against the first edition of Manifesta in Rotterdam because Manifesta accepted sponsorship money from the Tobacco industry, and Haacke was a hardcore anti-tobacco advocate 20 years ago. Hans Haacke is someone whose work I take very seriously, so I find interesting that he was anti-Manifesta, though for other reasons.

Manifesta also has a track record of finding itself in unsavory political situations due to its choice of locales. In 2006, Manifesta was scheduled to take place in Cyprus but was canceled by the government-appointed art commission amid tensions at the island's Greek-Turkish border. Does the exhibition just have very bad luck?

It also has to do with getting caught up in the opportunism within the art world. That edition's cancellation is actually a very unresolved issue. There was a participant in the show who is very astute businessman and an intellectual and an artist, and he played a very questionable role in this thing. I can’t really tell you more because I wasn’t a part of it, but I know there are still many unresolved questions about it. It’s kind of a soft spot of Manifesta, and I think we all have to deal with our soft stops. It’s very important.

Pavel Pepperstein's The Convict (2013)

Pavel Pepperstein's The Convict (2013)

You grew up in the immediate aftermath of World War II and the Nazi era in Germany. St. Petersburg played a dramatic role in that war. Did your experience of that period have any impact in your way of thinking about your show?

But you see at the time when I was born, in 1943, one million people died in St. Petersburg because they had no food, no water, no heat. And the Germans tried to occupy Leningrad but they didn't manage to do it, so the city was cut off and people just died because they had no basis to survive. The big question is, what did Stalin do during that time? Maybe he felt that St. Petersburg as a city was too aristocratic, too much of old world, and not the place where the new Soviet human being could be constructed. So the whole thing is so complex, and it’s very tragic too.

Personally, I objected to the army, but then, hell, I’m not a pacifist. You can't generalize. I could never say how I would have behaved during the Nazi time if I had no courage, no pity, no soul. You can’t tell. So therefore I’m very skeptical, and that's why I'm interested in art, because when you talk about art you begin to differentiate—you can know what you're talking about. For instance, with the Matisses, I wanted all of them to be moved into the new building so that the tourists have a reason to look at contemporary art—the Russians would only come if they saw something they wanted to see. And I was asked by my colleagues there, "Why Matisse? Why not Gauguin, or Bonnard, or Picasso?"

I said, "Because to me, Matisse is kind of like Buddha." It's very traditional in one way and very modern in terms of paint, color, and pure form on the other hand. So you begin to look at things differently—it’s not just in terms of style and in terms of continuation and rupture. So it’s another way of experiencing things.

You have curated so many exhibitions, worked at many museums, taught at many schools, and spent a life working with contemporary artists. What would you say is the role that art plays in society?

Unfortunately, the circumstances in Russia have not allowed an immediate presence of good art for a long time. There have been all these traveling exhibitions from the Saatchi Gallery or other big-time galleries with top names and third-rate work, and obviously some people have been privileged in that they are able to travel and visit galleries and museums in other cities. But the enlightenment and all of the progresses of the 20th century have been suppressed in Russia.

A still from the video of Elena Kovylina's performance Equality (2009)

A still from the video of Elena Kovylina's performance Equality (2009)

What circumstances do you feel need to change in order for the art community to be viable in Russia?

All the time I've been aware that I’m just a guest here, and I don’t speak the language. I will go to Siberia and travel around the Urals because I just want to get a sense of this enormous big country. You know, it’s bigger than America and Canada and Alaska combined, and that's probably one of the biggest problems they have. It’s just too fucking big, and in order to grasp it they have all of these kinds of ideologies and repressive momentum.

And what is really unfortunate is that if you travel as I did a lot between St. Petersburg and Berlin, you see that St. Petersburg is kind of on the edge of Europe—it’s the window to Europe. And you are caught in place that gets Western TV reception and Eastern TV reception with reports on the economy, politics, and so on, you really go nuts—watching Russian television, you really feel like a subject of brainwashing. It’s horrible—it’s all propaganda. There are debates about Russia, and one sociologist will be introduced as a friend of Russia, or as a person who understands Russia, and so on, which is very condescending. There are too many, and too much repression.