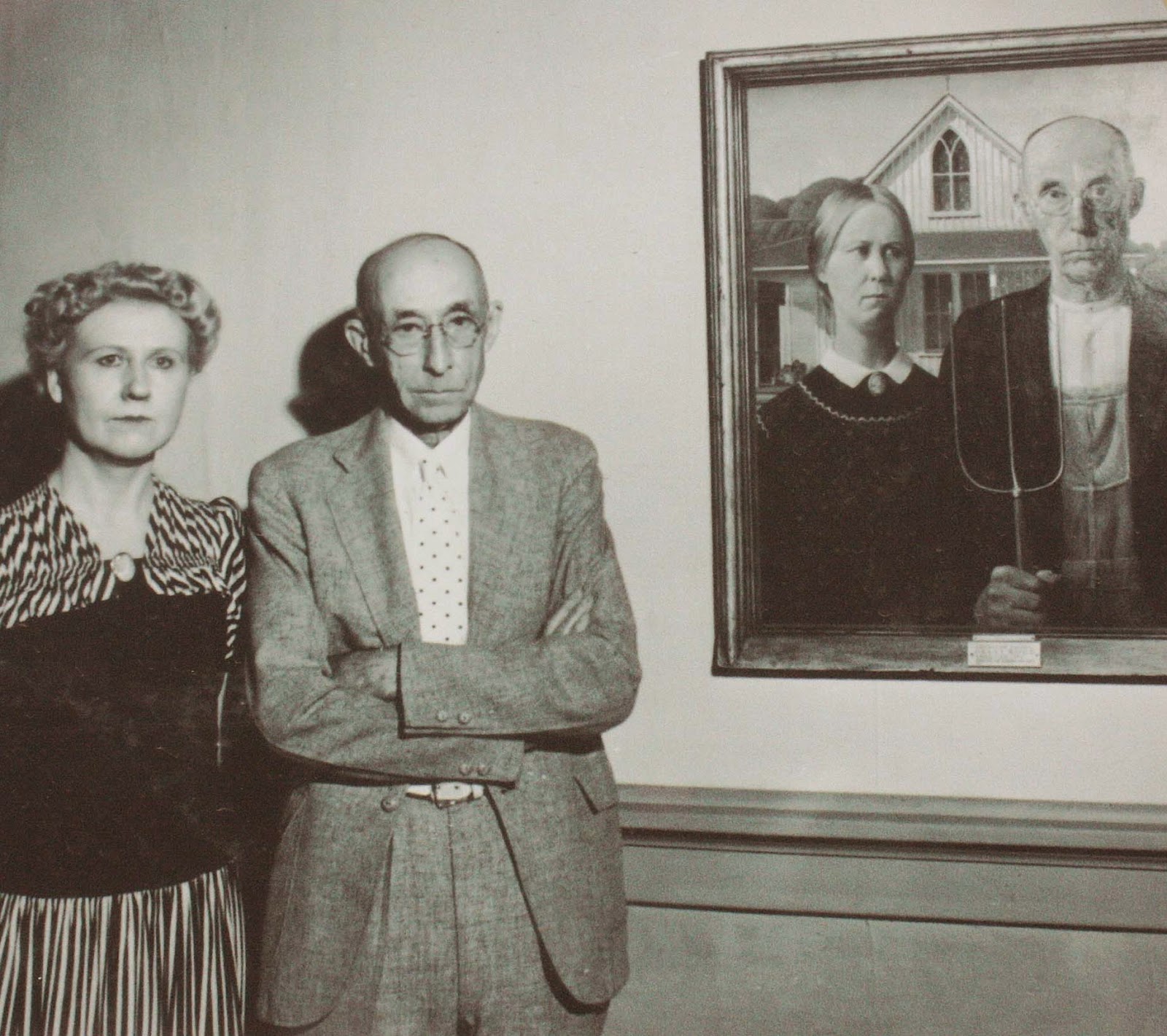

Have you ever stared at a portrait and wondered who the seemingly anonymous subejct was? It’s a question that historians, critics, and everyday museum-goers ask often. It took centuries of speculation before Mona Lisa’s true identity was confirmed in 2005 (scholars have concluded it’s Lisa del Giocondo, and that her husband commissioned the work in 1503). The artist–model relationship can be a complicated one that differs between artist, medium, and context. There is no set formula for how an artist chooses their model, and how that decision effects the final artwork. Sometimes, the model detests their portrayal in the piece—as was the case with Grant Wood’s sister, Nan, who modeled for his iconic painting American Gothic (1930). In the painting, Nan poses alongside the family’s dentist, and her mean mug makes her look much older than she actually was at the time. According to curator Elizabeth Botten, "the public reaction to the painting was so rough on her that her brother Grant felt bad for her." He tried to redeem her image the following year through the softer, more effeminate painting, Portrait of Nan (1933). Unfortunately for Nan, she’s largely associated with the former, more famous work.

Photograph of Grant Wood’s sister, Nan, and his family dentist, Dr. Byron H. McKeeby. Image via Artips.

Photograph of Grant Wood’s sister, Nan, and his family dentist, Dr. Byron H. McKeeby. Image via Artips.

The artist-model relationship can get messier when the term “muse” comes into play. This word—originating from Greco-Roman mythology to describe goddesses ruling over the arts—has traditionally been used to label a woman who is the source of inspiration for a male artist. The gendered nature of the word stems from the fact that historically women were not allowed to be artists, instead serving as muses observed through the male artists’ gaze. The term conjures up sexualized notions of infatuation and obsession, and can often lead to a problematic relationship due to power imbalances and lack of boundaries. For example, after Japanese photographer Araki’s recent retrospective at New York City’s Museum of Sex, his longtime “muse” KaoRi revealed that she felt exploited by the artist. Huffington Post writes that “KaoRi’s account of her experience as a muse—damaging yet not illegal, promising yet ultimately dehumanizing—illuminates the potential pitfalls of the oft-romanticized role. Like KaoRi, many women who become muses are young, inexperienced and hoping to break into the art world themselves, entering a field without well-defined expectations or compensation standards.” Clearly, being a muse can add to the complexity of modeling for an artist.

Detail of Nobuyoshi Araki’s “KaoRi Love,” 2007 (diptych). Image via Huffington Post.

Detail of Nobuyoshi Araki’s “KaoRi Love,” 2007 (diptych). Image via Huffington Post.

Here, we’ve compiled individual accounts by models to reveal the actual people behind famous works of art. The experiences show that no artistic process is identical, and that models have more influence in the relationship than they're typically given credit for.

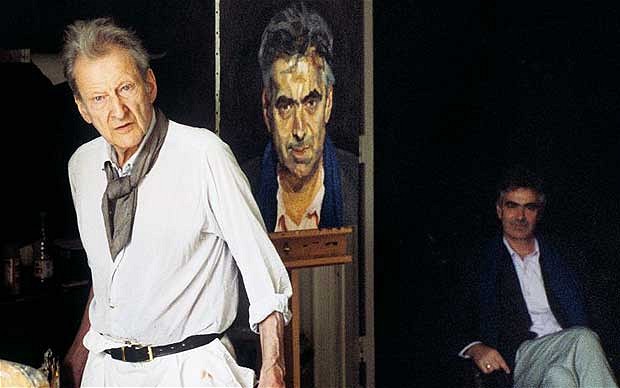

MARTIN GAYFORD

(

Lucian Freud

model)

Image via Telegraph.

Image via Telegraph.

Writer and art critic, Martin Gayford, initially wanted to sit for Lucian Freud to learn what it was like to be painted. Gayford had known Freud (a German artist renowned for painting psychologically complex portraits) for about a decade through the art world; the two spent time together dining, going to jazz concerts, and attending art exhibitions. Over a year and a half (2003 to 2005) Gayford sat for two different Freud portraits: one oil painting and one etching. He kept a diary of the experience, which he published in 2010 and named after the title of his portrait, Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud . In the book, Gayford describes the sitting process as tedious, recounting how he needed to cross his legs in the exact same position repeatedly. While there were periods of intense concentration, talking was very much a part of the process—they chatted about Freud’s artist friends, like Max Ernst and Francis Bacon—but, the more they talk, the more sidetracked Freud would become, and the longer the session took. After a sitting, Freud and Gayford would usually eat dinner together, since Freud liked to connect emotionally with his models; he thought it made their feelings come through in the work. In the piece, Man With A Bue Scarf (2004), Gayford’s fascination with the whole process is visible in the painting, as he passionately examines Freud painting him. Gayford describes how a month later, once they began working on the etching, it was completely different. “With the change in medium everything altered—including me.” Gayford was preoccupied with the book he was working on, so he wasn’t as present during each sitting, and they had less and less to say to each other. Gayford writes that it was “a good lesson in the complex nature of portraiture.”

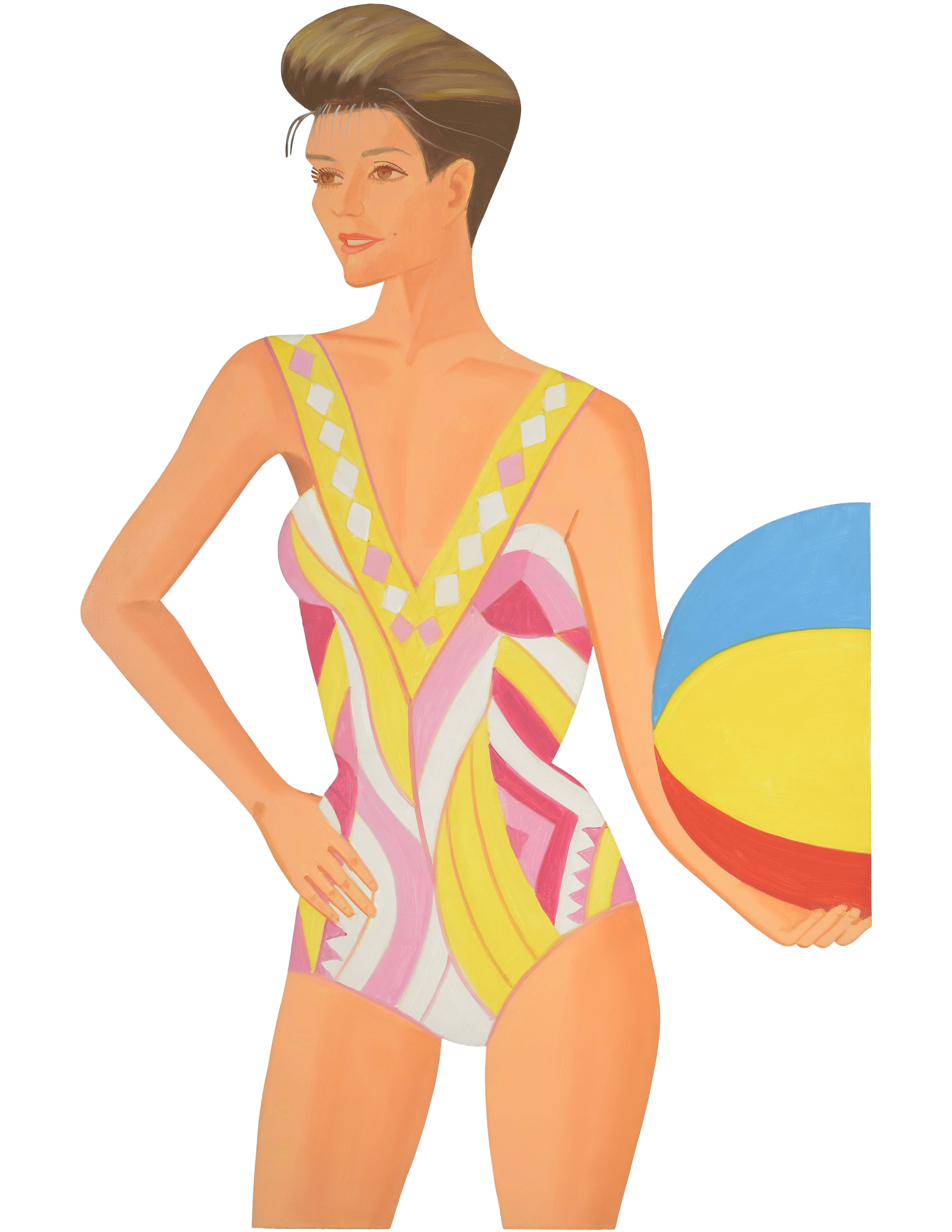

DARINKA NOVITOVIC CHASE

(

Alex Katz

model)

Alex Katz,

Chance (Darinka)

, 2016. Art © Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Alex Katz,

Chance (Darinka)

, 2016. Art © Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In 1984, during her first week living in New York City, Darinka Novitovic Chase was introduced to Alex and Ada Katz by their son Vincent, a friend of Chase's sister. They invited her to dinner, and afterwards Katz—an American figurative artist known for his bold use of color—asked her to pose. She sat for about eight paintings, and each required three to four sitting sessions of no more than an hour long, always during the same time of day to keep the lighting consistent. Katz would talk verbosely during these sessions, which made the otherwise static experience lively and exciting, Chase tells Artspace . Sitting for Katz was intellectually stimulating, but not too physically challenging, says Chase, as he doesn’t require his models to be completely still. When defining her relationship with Katz, Chase intentionally doesn't use the word “muse.” She says, “Posing for Alex is better than going to a French New Wave film; it’s like being in one. I never thought of the finished works as portraits of me—just as great paintings.”

JESSIE MANN

(

Sally Mann

model)

Sally Mann,

Candy Cigarette

(1989). Image via The Public House of Art.

Sally Mann,

Candy Cigarette

(1989). Image via The Public House of Art.

American photographer, Sally Mann, first gained notoriety when her photo series Immediate Family was exhibited in 1990 at Edwynn Houk Gallery in Chicago and then later published as a monograph by Aperture in 1992. The photos document her family’s ordinary lives, which of course involved nudity, intimacy, and children—giving some critics reason to falsely accuse the photographer of child pornography. Mann’s oldest daughter, Jessie, loved modeling for her mother. Now 36 years old and an artist herself, Jessie says she was offended that people assumed she and her siblings were being exploited, when in reality, she felt that she was an active and willing participant in her mother’s art. In an interview with Bleek Magazine , Jessie Mann addresses this idea of the “tragic muse,” a theme she has tackled in her own art. She says, “All of these conceptions we have about the role of the model, I think are simply because women are most often the subjects in art. It reflects a viewpoint where women are vulnerable, weak, and at risk of being exploited. Why is it so hard for people to conceive of the subject as a willing participant in the art making, as an involved and self-determining agent in the production of the image, or film, or painting, what have you?” Jessie explains that she wasn’t simply modeling for her mother, as much as she was collaborating with her and learning from her artistically. Sally Mann didn’t want to release the photos until the children were much older, but they encouraged her to publish them because they were proud of the work they had all done. Clearly, modeling for her mother didn’t destroy Jessie Mann; it did just the opposite—it allowed her to grow up in a creative space which influenced her artistically as an adult.

LAURE

(Édouard Manet model)

Édouard Manet,

Olympia

(1863). Image via Huffington Post.

Édouard Manet,

Olympia

(1863). Image via Huffington Post.

One well-known muse in art history is Victorine Meurent, who posed for French painter Édouard Manet in 1863 as the fictional prostitute Olympia. But in typical euro-centric, bigoted fashion, it wasn’t until recently that people stopped to ask, “Who’s the woman holding her flowers?” Laure (also referred to as Laura) is the other model in Manet’s then-scandalous painting depicting Paris’ 19th century brothel scene. An article by Beth Gersh-Nesic in Bonjour Paris utilizes three studies (an unpublished senior thesis for Vassar College, an Art Bulletin article, and a paper presented during the 2017 College Art Association conference in NYC) to uncover this woman’s role as a model in 19 th -century Paris. Based on Manet’s notes in a journal from 1862, Laure lived in an apartment that was about a 30-minute walk to Manet’s studio. It’s not confirmed exactly how Manet and Laure met, but some speculate that she was a friend of Victorine Meurent who recommended her to Manet. Others have suggested that Laure modeled for the students in Thomas Couture’s atelier, where Manet practiced from 1850 to 1856. She sat for Manet as early as 1861 in Children in the Tuileries and also in 1862 for Laure (aka La Négresse) . Her inclusion and participation in the French art world during the 1860s shows that while depicting a “free” black person was accepted and even trendy, the fact that Laure only appears as a maid, wet nurse, or nanny shows the limited status and opportunities for women of color during this time.

HALEY MELLIN

(

Chloe Wise

model)

Image via GARAGE.

Image via GARAGE.

Emerging Canadian artist Chloe Wise paints portraits to explore cultural notions of “guilty” pleasures. Haley Mellin interviewed Wise for GARAGE , and had her portrait painted in an effort to learn more about the artist’s process. Wise begins by covering her models in coconut oil so that the light reflects off of them in a painterly manner. She then takes photos on her Google phone. After composing the image quickly with her phone, Wise then creates a fictional background, placing the model in a seemingly photoshopped setting. Mellin expressed to Wise, “When I posed for a portrait with you, I got the sense that you really connect to the individual you’re painting.” Wise responded that her portraits are always personal in many ways, since her models are typically friends or people that mean something to her.

ENA JOHNSON

(

Kehinde Wiley

model)

Image via NBC News.

Image via NBC News.

American portrait artist Kehinde Wiley repurposes the imagery of Old Masters to spotlight contemporary black individuals, questioning historical conventions of race, class, gender, and beauty standards. Holland Carter of The New York Times calls Wiley, “a history painter, one of the best we have.... He creates history as much as he tells it." Wiley recently went down in history for painting the official presidential portrait of Barak Obama. In good company, Ena Johnson modeled for Wiley when she was a 25-year-old nursing student. She told NBC News that the sitting started with a slight wardrobe malfunction—the bust of her Givenchy gown, designed by Ricardo Tisci, had to be clipped up since it didn’t fit properly. She said Wiley was extremely disappointed and apologetic. For Johnson, the experience was “like a dream come true.” She said she would gladly do it again since Wiley’s paintings “are an amazing testament to the strength and beauty of black people… in these paintings it is refreshing how we are portrayed and something that should be done more.”

DEE PARKER

(Andrew Wyeth model)

Dee Parker met American realist painter Andrew Wyeth in 1982, and was soon invited to Maine to be his granddaughter Victoria’s nanny for the summer. She first posed for Andrew in Victoria’s playroom, sitting for several days. Wyeth’s works-in-progress were always a secret, so their sittings were confidential and she couldn’t tell anyone she was modeling. He also never planned a sitting in advance; he would spontaneously call Parker and ask if she could come pose for him. At the end of the process, Wyeth would never reveal the final work. Parker recalls other sitters warning her, saying, “You won’t know it’s finished, but then someday you’ll see it at the Whitney.” From an outsider's perspective, it seems this relationship is text book exploitative. But Parker, who is also an artist, has said that the relationship incouraged her own practice; Wyeth told her to keep up her painting and drawing. Ultimately, Parker modeled for six Wyeth paintings, including one nude portrait. According to the model, the most difficult painting she posed for was Snow Hill (1989) , since she had one foot on a stool, and was standing on tiptoe with the other.

ZEN

(

Jordan Casteel

model)

Image via Art21.

Image via Art21.

Up-and-coming American figurative painter Jordan Casteel uses the people in her community as models. The artist, a Harlem resident, doesn’t have people sit for her—but instead photographs them in a fleeting moment before spending hours deconstructing that scene back in her studio. Capturing subjects in the moment allows her to examine details and people that might otherwise go unseen. Casteel photographed Zen when he was walking his dogs in Harlem. He sat and posed for the photo, and then exchanged information with Casteel. Zen attended the opening of Casteel’s first solo gallery exhibition at Casey Kaplan in Chelsea, which Art21 documented. While looking at his portrait, Zen discusses the importance of modeling for Casteel: “There are very few spaces where black men are being represented outside of criminality and entertainment, people probably pass the subjects in this work everyday, without acknowledging anything about them. There is a value in just being.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

Jordan Casteel on Painting Black Men—Watch the Video

Mieko Meguro's Current Exhibition has a Harrowing Back-Story About Dan Graham and Potato Chips