The paintings of Francis Bacon (1909-1992) occupied an odd place between figurative art and Surrealism. Disconnected figures, altered forms and dismembered parts were presented, but with a deeply human, visceral, tactile quality. A new show at the Royal Academy of Arts – Francis Bacon: Man and Beast – explores this physical aspect of his work more deeply, through the lens of his fascination with animals. The prolonged studies that Bacon undertook of these forms – through trips to South Africa, an extensive collection of wildlife books, and the 19th century photographs by Eadweard Muybridge of physical motion – informed his studies of people, and presented the idea that when pushed to the extremes of existence, living figures are barely distinguishable from one another. As the exhibition catalogue says: ‘Whether chimpanzees, bulls, dogs, or birds of prey, Bacon felt he could get closer to understanding the true nature of humankind by watching the uninhibited behavior of animals.’

The show spans Bacon’s entire career, including his final ever painting, rarely-loaned works from private collections, a trio of bullfight paintings which will be exhibited together for the first time, and one of the artist’s landmark paintings, Head VI. The source material for this painting was a portrait of Pope Innocent IX from 1650 by the Spanish painter Diego Velazquez (1599-1660). Bacon never saw this painting in person, working instead from photographic references and placing the pope inside the geometric framework of a translucent box. That framing gives the character an oppressive air of silence, trapping him as if behind glass or underwater. Another line hangs through the centre of the painting – perhaps a curtain tassel or a lightswitch cord – further reinforcing the geometric lines of the image (the hanging cord was a motif that would reoccur in, and become a signature of, Bacon’s work).

The fabric of the subject’s robes sits in crumpled folds, the deep purple of the material contrasting with the brown, corporeal smears of the walls around him. Closer inspection of this aspect of the painting fully reveals Bacon’s technical mastery – surprisingly few of his forceful strokes are used to bring the Pope’s outfit to life, with negative space used as much as color to convey the feeling and texture of the velvet.

Installation view of the ‘Francis Bacon: Man and Beast’ exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (29 January – 17 April 2022) showing Francis Bacon, Head VI , 1949. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. Photo: © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2022

The focal point of Head VI is, unavoidably, the screaming mouth set at its centre. The inspiration for this part of the image is found a quarter of a century earlier in Sergei Eisenstein’s silent movie masterpice, Battleship Potemkin (1925). The film tells the true story of a Russian warship crew’s mutiny on the Black Sea in 1905 and made a huge impression on Bacon. ‘Of course, during the silent era, the image had tremendous force,’ he is quoted as saying in the book In Camera Francis Bacon: Photography, Film and the Practice of Painting. ‘The images of silent film were sometimes very powerful, very beautiful.’ In particular, he returned repeatedly to one of Battleship Potemkin’s most powerful shots: after Imperial soldiers and Cossacks have brutally massacred the population of Odessa and the camera lingers on the face of a wounded woman wearing glasses and screaming in fear and agony. Bacon spoke of how this image had ‘deeply impressed’ him, and her screaming mouth is clearly identifiable in the centre of Head VII, together with her spectacles.

The same figure would reoccur in later works by Bacon: Pope III (1951), Study for the Head of a Screaming Pope (1952), and a full length nude, Study for the Nurse in the Film Battleship Potemkin (1957). In each of these, as in Head VI, the screaming mouth becomes a void or a sinkhole, pulling the rest of the painting down into it, rather than expelling the image outwards. And in each, the thinly sketched frame sits around them, trapping the subject alone with their agonies in an airless chamber

Installation view of the ‘Francis Bacon: Man and Beast’ exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (29 January – 17 April 2022). Photo: © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2022

This was the last of a series of six paintings which made up Francis Bacon’s ‘1949 Head’ series. They were exhibited together in Bacon’s show at the Hanover Gallery organised by the gallerist and art dealer Erica Brausen, marking a hugely productive period for the artist. ‘The shock of the picture, when it was seen with a whole series of heads ... was indescribable,’ wrote the artist Lawrence Gowing 40 years later. ‘It was everything unpardonable. The paradoxical appearance at once of pastiche and iconoclasm was indeed one of Bacon's most original strokes.’

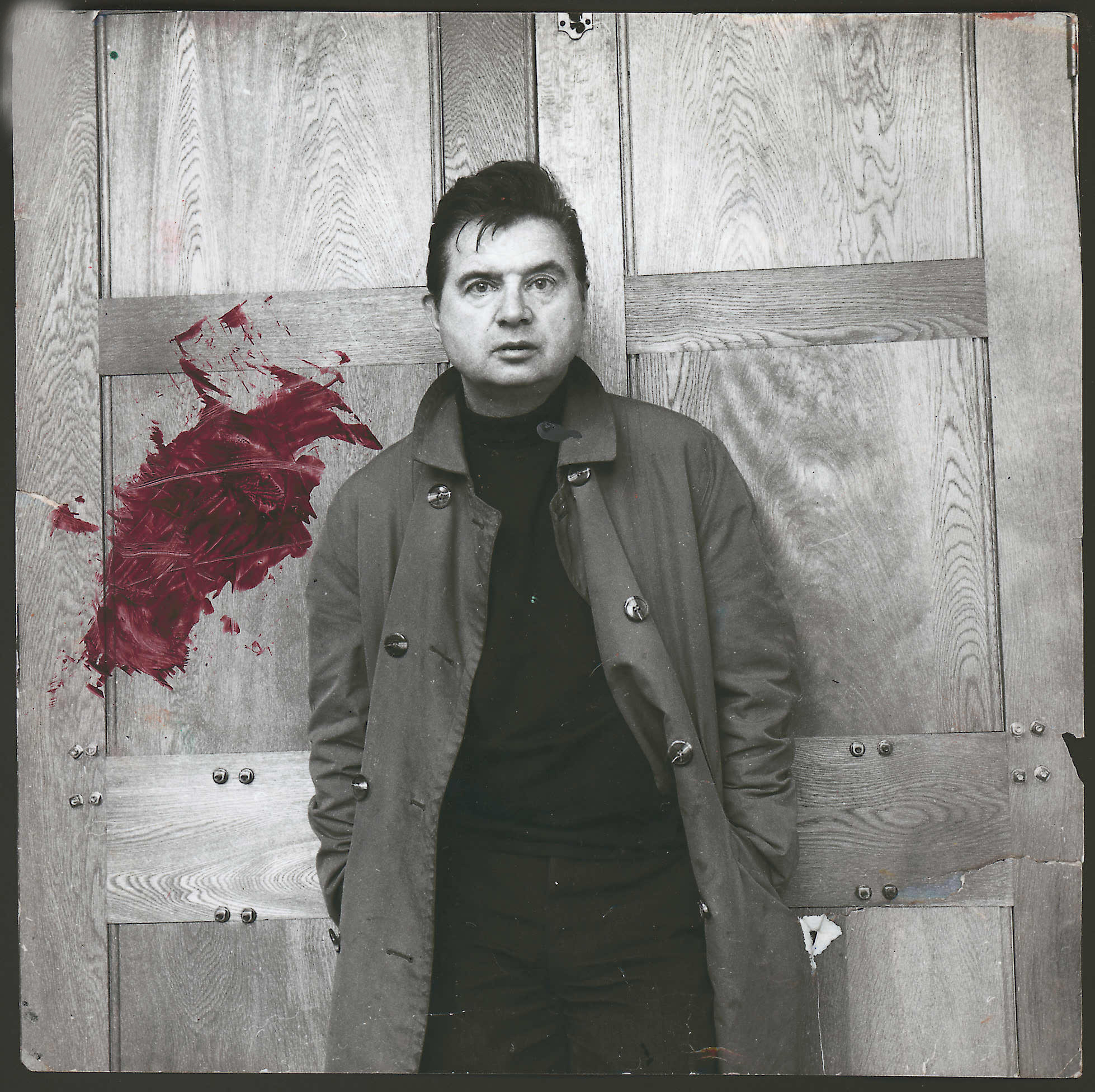

John Deakin, Photograph of Francis Bacon in Front of a Door, c. 1967 Photo © John Deakin Archive; Source Clipping

© The Estate of Francis Bacon

Having produced nothing that survived between 1947-1948, and having just turned 40, Bacon knew this show was a huge – perhaps final – chance to establish himself. The brutal, unnerving impact of all the series, but especially Head VI ensured that was the case. Writing at the time, The Observer’s critic judged that ‘The recent paintings ... horrifying as they are, cannot be ignored. Technically they are superb, and the masterly handling…only makes me regret the more that the artist's gift should have been brought to subjects so esoteric.’ Even now, the impact of Head VI remains undiminished.

Francis Bacon: Man and Beast is at the Royal Academy of Arts until April 17.