Amid his city's bankruptcy saga, Detroit native Gary Wasserman saw a flicker of promise. The rent was exceedingly cheap, the local collector base seemed unaffected by the metropolis's fiscal crunch, so Wasserman—a longtime art collector himself, and a member of the board at Miami's Wolfsonian museum—decided to go against the grain and open a gallery of his own. Throwing open its doors earlier this year as a roving pop-up space, Wasserman Projects now shows the work of such established and midcareer artists as Jane Hammond, Wim Delvoye, Markus Linnenbrink, and Joshua Abelow.

Most recently, Wasserman brought Detroit artist John Dunivant to New York City to perform his "Expatriate Parade" in the streets of the Lower East Side and at an exhibition at the Lodge Gallery. We spoke to Wasserman about the challenges and silver linings of Detroit's ever-evolving art scene.

Do remember the first artwork you bought? How did that purchase evolve into an ongoing habit of collecting art?

I think that my first "artwork" was a sensational 7-Up billboard by Peter Max, which I repurposed in my fraternity house bedroom when I was 18 or 19. It went up one wall, over the ceiling, and down the next wall—after that I was completely hooked. Surely my early purchases were erratic and most of the artifacts have been lost in time and divorces. The salient theme is that tastes develop and become more discerning and perhaps more focused over time. In fact, the next purchase that I remember making was a pair of antique Venetian mirrors with my first commission check, followed shortly thereafter by a pair of very '70s ceramic trees that are still around somewhere, and are still quite good-looking. I bought them at the Ann Arbor Art Fair, which was overstimulating at the time.

Do you have a philosophy that guides the way you collect? Are there any aesthetic trends that you have followed over the years?

I'm primarily interested in work that presents a great aesthetic appeal and provokes a visceral response, coupled with a distinct conceptual undercurrent. Many of the artists I collect produce art that is vibrantly colored, with touches of whimsy and fantasy. But, as I said, these artists, such as

Anish Kapoor or Wim Delvoye, will have a dazzling first impression that contains a more complex narrative beneath the surface. I make a point of knowing the artists personally as well as I can. This adds additional facets to my experience with their work, and I particularly enjoy seeing details of the artists' personalities emerge each time I revisit their pieces in my collection.

Why did you decide to establish Wasserman Projects in Detroit this year of all years, when the city is internationally renown for defaulting on its debts?

Wasserman Projects grew out of our excitement over the energy, vibrancy, and creative energy in Detroit. We would like to eventually have a permanent physical presence in the city. My original plan for this project involved linking together a commercial gallery together with a kunsthalle and residency program. I had the idea that a very nice local gallery, Lemberg Gallery, would be the ideal fit to partner with. Then the owner of Lemberg decided that she wished to retire, so I thought that I had better act quickly and decisively to retain a few of the exceptional artists and the outstanding director—and I was suddenly reborn as a gallerist! It is a remarkably exciting and stimulating adventure.

How has art scene in Detroit adapted to the city's bankruptcy? Do you see parallels between Berlin and Detroit, as some have suggested?

The bankruptcy is almost after the fact for most of what is happening culturally in Detroit, aside from the

existential threat to the Detroit Institute of Arts. Creative people have been drawn to Detroit in the first case because, like Berlin in the 1990s, it is very inexpensive. There is most certainly no other place where an artist or musician can acquire a 3,000-square-foot house with yard for $500. The city has been functioning, or not, as though it were insolvent for a number of years, so the actual insolvency makes little or no difference. Perhaps it even adds a new layer of cache.

Bear in mind that Detroit still has the cultural infrastructure from the time that it was the fourth-largest city in the U.S.: an international art museum at the highest standard of quality, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the Michigan Opera Theater, and arts-education institutions at the most elite level, such as the Cranbrook Academy of Art, the University of Michigan, and the Center for Creative Studies. A creative person can be immersed in every type of visual or musical experience, from classical to cutting edge.

But Detroit is not Berlin. The German government stepped in and invested billions to build a new capital city. A new European capital has been achieved, although, it is certainly not on the walking model of London, Paris, or Rome. Detroit is not going to become Chicago or Toronto, but it does have the opportunity to become an entirely new and as of yet undefined urban experience. That is perhaps one of the greatest sources of the excitement. Everything and every idea is possible because it is a void waiting to be filled.

Do you think Detroit has a strong enough collector base to sustain local galleries, or do you tend to sell to collectors outside of the city?

Detroit certainly has a sophisticated collector base. One should not confuse the challenges of the City of Detroit with the otherwise very solid and vibrant metropolitan area, whose inhabitants enthusiastically support the local arts institutions. Detroit has some very substantial and invested collectors, as well as a rising community of younger people who are very excited to try to be part of the energy. That said, even in New York, galleries must seek collectors outside of their geographic markets. It's well known that today the model of the art fair dominates sales, more so than direct gallery purchases. Yet the gallery is still necessary as the stage upon which the work can be framed and projects can be created, which ultimately also brings attention at the fairs. In our short life as a gallery, Wasserman Projects has been very well supported by both artists and collectors in the community, and has also sold in other parts of the country. The gallery scene in Detroit is no stronger nor more fragile than galleries everywhere adapting to the globalization of exposure and sales and searching for new successful models to support all stakeholders.

You work with the artist John Dunivant, who stages a massive art-carnival each year in a Masonic Temple in Detroit. This year, the event, known as Theatre Bizarre, received a $100,000 Knight Foundation grant. How did you first become familiar with Dunivant and why did you decide to bring his "Expatriate Parade" to New York City last month?

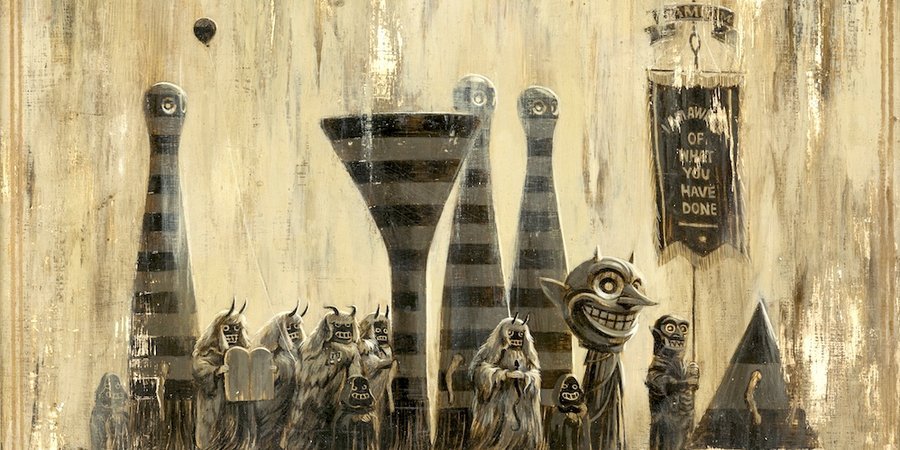

I first saw John's work at the Kresge ArtX exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. John was a Kresge Fellow, and therefore the work was in the show. As always, for me images, aesthetics, and forms have to be there, and when I saw "The Expatriate Parade" I was exhilarated. I wondered how it was that I was not familiar with this artist. Once I read some of the material and also got to know John, I understood the deeper and more poetic undertones of the work; the anxiety of displacement, a feeling of rootlessness, foreboding, and yet a fantastical hope for a better future. The parallels between John's journey, my own, and the life of Detroit all seemed so elegantly rendered in this fantasy work.

John is actually a cult hero in the city, highly respected and valued for his contribution to creating and sustaining Theatre Bizarre, a gigantic and complex event that could not be possible in any other place than Detroit. It all seems an articulate metaphor for exactly this moment in the community, with the Detroit Institute of Arts fighting for its survival, the city in bankruptcy, and yet incredible islands of hope in the downtown and midtown areas. It's all a powerful mix of the most frightening and the most optimistic. It's a perfect moment to step outside of Detroit and present the articulation of these conditions to the larger world, and what better way to announce it than with a marching band and circus performers in procession on the Lower East Side, escorting John Dunivant into New York City?

In what ways do you expect this year's Theatre Bizarre to be different from previous iterations?

Like all holidays, we want tradition and we want to be able to expect certain images to return and be present. But we also like something new and fresh as well. Theatre Bizarre is still in its early years at the gigantic Masonic Temple, and exactly how it rolls out will always be somewhat different than previous iterations. It is not a permanent architecture, but rather an illusion that appears and disappears. To that extent it will always be old and new. There are new attractions planned, new performers, and a welcome return of the expected and bizarre.

You have an especially eclectic taste in home decor, pairing bold contemporary works with rustic pioneer-era Americana. You also, rather extraordinarily, pursue the uncommon sport of racing vintage horse-drawn carriages. How do all of these interests converge?

My Michigan home is a farm that has been in my family for many years. As such, it is the single repository of my familial patrimony. My parents were also collectors, of antiques, equestrian objects, and contemporary art, and much of those collections is there. In fact, the large

Keith Haring wall relief was something my parents bought after Haring did a residency at Cranbrook many, many years ago, and it seems more at home on the wood paneling than it did on white walls.

I enjoy the contrast between objects and spaces and, quite frankly, I am a maximal minimalist. No white boxes for me! There is a great layering and richness that is gained when one allows contemporary works to be part of a more complex environment that does not strictly dictate the way in which one must see and experience the work. I actually live with my collection. I look at it and invite others to do so and find their own perspectives. And all of it is part of my own eco-system of art, architecture, and aesthetics.