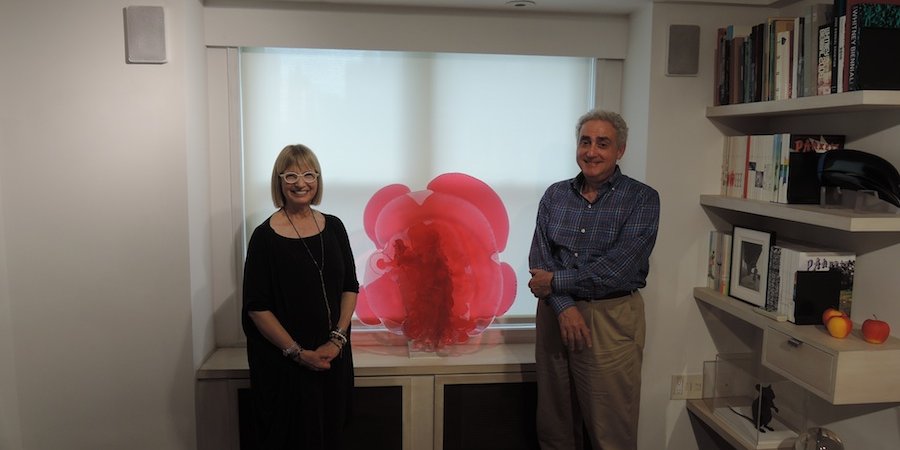

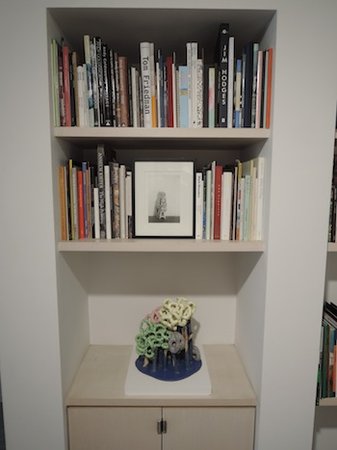

In an era when art collecting has become a high-octane pursuit for financiers looking to diversify their portfolios, Zöe and Joel Dictrow are holdovers from another time—collectors whose support of younger artists, innovative gallery programs, and the art world's grassroots borders on benificence. A former magazine advertising manager and Citigroup executive, respectively, the Dictrows have lived in the same West Village apartment for four decades, gradually expanding it as their collection grew by adding two neighboring apartments. A cozy warren of rooms, their home brims with work by artists from Gerhard Richter and Cindy Sherman to today's emerging stars-to-be, covering their walls, filling their bookshelves, and even, in the case of a bespoke installation by Sarah Sze , crawling across their ceiling.

Every year, the Dictrows open their doors to VIPs from the Armory Show for a collection tour that has become one of the most anticipated events of its kind, unveiling their newest acquisitions. But engaging with contemporary art is a year-round activity for the two, playing a central role in their lives. To hear about their approach to collecting, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein sat down with the Dictrows in their home to talk about their hard-earned insights into the art world, how they live with art, and how their pursuit of the new has brought them closer together.

As patrons of emerging artists, you have been especially supportive collectors when it comes to younger galleries, taking chances on new talents before the establishment catches wind of them. It seems that collecting isn't just a pastime for your—that it's really a way of life.

Zöe: It's true—this is our pleasure in life. We’re learning so much and enjoying ourselves and meeting interesting people, which is the great pleasure of the art world. Through art we find we have real connections with many different people who superficially would not appear to have anything in common with us, age-wise, culturally, professionally, or economically. It’s such a vast little world, which sounds strange, but it really is a huge number of people to be able to relate to.

You are known for always collecting together, so I would imagine you have exceptionally similar tastes in art. How do you go about deciding on an acquisition?

Zöe: Well, we do agree on a lot, but we also have our own personal directions.

Joel: There are certain things that she leans toward and other things I lean toward. Our standard for compromise depends on how expensive it is. If a piece is not too expensive, then we say, okay fine, we’ll indulge you or me. If it’s reasonably expensive, then we use the “over my dead body” standard. There are couple of things that I wanted and Zöe said, “No way.”

Zöe: You can only invoke “over my dead body” if you really hate it. I mean, it has to be really objectionable. And then, you may want it, but it’s probably not going up. [Laughs] Because I’m the one who, at the end of the day, puts the art up in the apartment, and maybe we can’t find a good spot for it. It’s got to feel right. You’d be surprised how many different arrangements you need to try. The Richter, for instance, can be very tricky. We move that around the apartment—right now it’s probably the sixth or seventh place we’ve put it. Sometimes you can put something next to it and the Richter just slaps it down. It could be something very interesting, but not next to a Richter!

Would you say the Richter is the centerpiece of your collection?

Zöe: It’s an important part of the collection for a few reasons. One, we love it. It’s a great trophy, as you know. But, also, artists are very excited about being in a collection that has a Richter. We once put up a work by a young German artist on a wall with the Richter and a Richard Prince, and when I told the gallery about it and the dealer said to me, “Can you send me a picture of it installed in the room, so that it shows up with the other art?" I sent him the picture, he sent it to the artist, the artist sent it to his mother, who said to him, “Wow, you really are an artist.” [Laughs]

When did you buy the Richter?

Joel: There was a joint show at Sperone Westwater and Marian Goodman in 1986, and we went into Sperone Westwater and said to Angela [Westwater], "I hear you’re having a show of Gerhard Richter." And she said, "Yes, and here are all the slides." [Laughs] And we said, “Oh.”

Zöe: Back then, in the mid-'80s, the abstract Richters looked garish, and we couldn’t afford the realist Richters. But we were very interested in the abstracts.

Joel: The truth is that the price of the abstract Richter was very expensive for us. We both were employees of different institutions—I worked for Citigroup at the time and Zöe worked in advertising sales at a trade publication. And the price actually changed during the course of the month because the Deutsche Mark went up against the dollar and added an extra 10 percent to the painting. We were like, “Are you kidding?” It's so expensive.

Now the consensus on Richter has flipped to the point where the abstract canvases are the ones that make headlines with record auction prices.

Zöe: Oh, we knew it was a gem. But it did take a long time to realize certain things about it. Why did he make these marks on this painting? It’s obvious that he had a perfectly beautiful painting and then he made these finger marks or brush marks on it, very heavy strokes. I realized that he had taken a tremendous chance with a perfectly beautiful painting that probably looked like it was done, and then he said, "No." He wanted something more, and I think the painting is very profound a result. It’s almost like a defiance of the pretty picture

It's like a performance, or a high-wire act. I can see how that could make other paintings look weak in comparison.

Zöe: It wasn’t even that the other painting was weak, it's just the artist wasn’t a giant. Richter's a giant! And, you know, you don’t get to be a giant until you’ve had a great deal of experience.

It's interesting how you say you divide the roles of collecting between the two of you, with Zöe curating the display at home. Joel, what part of collecting are you especially drawn to?

Joel: Well, I’m a born collector. And, interestingly, Gene Schwartz, a great art collector whom we loved and knew forever, said that “art collecting is the only commendable form of greed.” Because if you collect art, then it's okay.

Zöe: You just want something desperately. It’s really is a kind of a greed. But that’s also what tells you that a piece is important to you, even if you don't know exactly why—you just really want it.

Joel: For me it started with a stamp collection I had when I was a kid, all the way into my early 20s. I collected all these stamps and then I put them away and never looked at it again. I recently sold the thing, thank god, because it was clogging up our storage. It was probably a couple thousand stamps, but it wasn't worth anything. Stamp collecting is a whole different world now. It's for older people and it’s starting to die out. Younger people don’t collect stamps.

You don't really need them to send an email these days. But evidently that acquisitive urge has translated into your art collecting.

Zöe: He really likes the whole idea of the tangible aspect of art, and it certainly brought out an animal side of me as well—I want a bite too. And very often I know something is really interesting because it comes back to me almost unwilled. It's not like I remember everything I see, so if something comes back to me, I’ll want it.

How did the two of you start collecting art together?

Zöe: From the beginning we were putting things that we liked up on our walls, and we’d go to museums, but we weren’t real collectors. Then, when I was between jobs in the early '80s, I was uptown for an interview and I looked up art galleries in the newspaper to have something to do after. And I went up to Cordier & Ekstrom, a famous gallery at the time that was where Gagosian is now, and I saw a show I liked and said, "Joel, you have to come and see it."

Joel: She would say to me, “I saw this sculpture and I really liked it.” And I'd ask, “How much is it?” And she said, “$5,200,” and I said, “Are you crazy?”

Zöe: I'd say, “But just come and look! Look at these things, they’re interesting and beautiful.” So then we started going to galleries together, and we really liked it. We were pretty young and had been married for several years, and it was an interesting activity. And we have all these walls to fill!

So, how did you go from collecting art to fill your walls to collecting enough art to fill your walls many times over?

Joel: Well that goes to Barbara and Gene Schwartz, who we fell in with on a trip to the Caribbean. We used to take a trip to the Caribbean once a year, and they happened to be at the same hotel, and every night Gene and Barbara would sit down with us and talk to us about collecting art. Then, when we came back, they were on cover of New York magazine for their collecting. [Laughs] They were the precursors to Saatchi and the Rubells . People would follow them—if they bought something, then everybody would buy it.

Zöe: They were trendsetters, some of the first people to collect Basquiat .

Joel: So we would sit down with them and discuss collecting, and I'd ask probing questions like, "What do you do when you fill up your walls?" [Laughs] And they would say, “Storage!” And I'd say, “Storage? What on earth is that?” Because the truth of the matter is that we weren’t involved in the art world at all—we were just running around buying things, and we had no idea what we were doing.

Zöe: Then we met some other people who were also big influences on us, like Eileen and Michael Cohen. When you start hanging out with other collectors and talking about art it fuels you to collect even more. And then once our son was in college we could travel to other countries and look at art. We picked art fairs around the world in places we wanted to visit, so we'd go to Basel or Mexico City or Madrid or Belgium and get to know a new city.

Joel: Most recently we went to FIAC, and we hadn't been to Paris in 20 years. We said, “This is Paris!” FIAC was great, and we had a marvelous time in Paris.

What I find very interesting about your approach to collecting is that wherever you go, you always gravitate to the newer work by younger artists. Why is that?

Joel: Well, we had limited budget, especially in the '80s and '90s, so we always looked at the newer art because that was the only thing we could afford. You know, over time this obviously evolved a bit, but it’s still pretty much that’s the case. The thing is, the escalation of prices has been extraordinary.

Zöe: I mean, we used to value the art that we bought as basically zero. I think even up to 2000 we said the value of the collection was zero. It was only at the end of the '90s that we started to realize we had things that were very, very valuable. At the same time, we had to think more seriously about what we were buying because things were getting more expensive. You couldn't just look at something and say, “Gee, I like it—I’ll buy it.” Things got so expensive that you had to really, really want it and justify to yourself why you think a piece is meaningful enough to purchase.

What is your criteria for that kind of consideration?

Joel: It’s a couple of things. Clearly, we think about where an artist is in the scheme of the art world—are they at the beginning of something or not? And we always say that we listen with our ears, but we use our own eyes. If something tells us to look at something, we you look at it seriously. It doesn’t mean we buy it, it just means we look at it, and we use our own eyes to make the determination whether it’s something we want.

Zöe: Also, when a gallery we respect represents an artist, that's always a big thing for us. We'll go to the dealer and say, “This is interesting. What made you represent this artist, or this work?”

Joel: We always buy from galleries and not directly from the artist because my feeling is, let them do the legwork and then also let them make the money. Because we support the whole system, whether it’s galleries, museums, curators, what have you.

Zöe: There are approximately 40,000 artists graduating every year from art schools, and when an artist gets represented that's really when they start their career. For that to happen, the gallery has to decide to show this artist in one show after another, so they have to feel there is a future. And part of the joy is being able to follow an artist as they develop. You say, “This an artist who looks like they have a lot to explore.”

Joel: If we walk into a gallery for a show by an artist and there's only one painting of interest, we’re not interested in that artist. We like to be able to appreciate the whole body of work. It’s a whole different philosophy, and that’s why we keep going to galleries.

One reason some collectors like to buy directly from artists or at auction is to bypass gallery waiting lists. What is your experience with those kinds of hurdles?

Joel: Every hot artist has a waiting list, but that’s meaningless. Who’s kidding who? Because if a gallery chooses to place a piece with a particular collector or institution they will. They just say, “Screw the waiting list" and sell to whoever they want.

Zöe: Other times a gallery will tell us, “We want you to have our work,” and then show us something, and we’ll say, “That?” [Laughs]

Joel: There are four categories of art collectors. In the first are the major museums, and they get whatever they want. That's the reality. If MoMA wants it, MoMA gets it. Second is minor museums, like college museums or other associated museums. The third category is people who are important to the gallery and major collectors. The fourth category is everyone else. The key is to get to that third category. And sometimes when it’s minor museums versus big collectors the dynamic flips over that’s the reality. So a smart approach is to focus on certain galleries and support those galleries, because then they see you as important collectors.

Zöe: What I think is interesting today is that even the very large galleries are now representing younger, so-called emerging artists, like Hauser & Wirth, and that's very problematic for the smaller galleries. They are now in direct competition with the large galleries.

Joel: We have a theory that there are seven levels of galleries.

Oh, I would love to hear this.

Zöe: There are seven levels to galleries. There's the emerging gallery that basically has a small second-floor space. They are puppies. Everyone loves a puppy, and they get a lot of attention. In today's market they generally sell works that are $10,000 and less. Then there's a second level where they can sell works up to $20,000, or even $30,000 on occasion. But if they’re not one-man bands, they're pretty close—very often it’s two partners or a husband-and-wife team and no real staff. If they're in business for five years they usually have the ability to start doing some art fairs if they have some cool factor.

By the third tier, you can afford to have somebody working for you, so you can travel a little bit and not leave the gallery unattended and you’re definitely doing art fairs at this point; you can sell works that are between $10,000 and $40,000, though most of your artists are still at the more modest level. Then the fourth tier is when you can get larger space on the ground floor—that's generally when you've been in business for about five to 10 years. You’re living modestly, but you’ve survived. Maybe you can afford to buy a house, you can afford to get married, and you can have a life outside the gallery—you’re not clawing your way to the middle anymore. You’re in the middle! You’re solid.

And then once you hit the sixth tier and you're in with the Gladstones and Sean Kellys and other major galleries. The seventh tier is a small handful: Gagosian, Pace, Hauser & Wirth, Zwirner , Matthew Marks, Marian Goodman, White Cube . You have multiple locations around the world, and you represent artists who command very substantial prices, mostly $100,000 up to $1 million or more.

The thing is, as I said, those top-tier galleries are now also looking below. They have so many spaces to fill that they can represent artists at every level of the art world. So this is a very big change, because that means that the galleries anywhere from the sixth tier down to the third tier can lose their artists to the biggest galleries.

As collectors who have been following gallery programs so closely for so long, you must have seen a lot promising galleries come and go.

Joel: Yes, but also to grow. I mean, look at David Zwirner—he was downtown in SoHo in a relatively modest ground-floor space and look at him now. He grew all of that out.

What is it that makes a gallery succeed? Is it luck?

Zöe: Tinkerbell dust. I don’t know. [Laughs] Who knows? There are a lot of X factors.

Joel: Why do artists suddenly go from $15,000 to $80,000 to $100,000? I don’t know. If we knew that we would be acquiring works by these artists all the time. But it seems that now there's a whole new wave of hot artists who don’t want to be affiliated with galleries and want to be free, and their prices are ginormous.

Considering that you obviously have much more art than your house can comfortably hold, do you ever deaccession works in order to buy new ones?

Zöe: Yes. We have to do that.

What is the proper way for a collector to go about doing that?

Zöe: Whoa. That’s a tough question.

Joel: It’s depends on our relationship with a gallery. If the gallery still represents the artist in question, we almost routinely go back to that gallery unless there was a major problem. If they’re not interested, that’s fine, but if they are interested, we’ll work with that gallery because they're the ones who sold it to us in the first place, and we're part of their support system.

Zöe: But let’s say a gallery says they can get you X amount of money, and it’s a lot less than the amount you can get some other way, then it can be hard to be loyal under those circumstances. [Laughs] But really we're recycling, because the money is going to go back into art, and we’re not going to hurt the artist.

Joel: We never do that. That’s an absolute rule.

Zöe: But with artists who have established markets, you’re not hurting the artist no matter how you sell.

Joel: There’s this whole theory that occasionally if you sell an artist on the secondary market and he does well, then it helps the artist create a real secondary market, which then helps their primary market. But there are some issues. If it fails to sell, that’s an issue. If it sells at a moderate price, that’s a good thing. But if it sells with a high price, that drives more stuff out into the market. And this feeds on itself.

Zöe: There is one piece by an artist that we got from a gallery where the owner has since become deceased. So we sold it into the auction market and the price was great! If the gallerist was alive, we probably would have brought it back to the gallery. But we hit a moment when the market was hot for the artist.

We're in an interesting moment right now, when there are a lot of artists who are very young and whose work is flooding the secondary market and selling for skyrocketing prices.

Zöe: That’s going to bite them in the butt. The market is frothy right now.

Joel: Also, the market is subject to fashion. We’ve seen that time and time again, where when you hold on to something for a long time and it goes way up in value, and then it goes way down.

Zöe: We have plenty of things like that. Down, up, down, then maybe later up. I mean, we’ve been collecting a long time. But very often once an artist becomes no longer attractive to the market, they stay unattractive to the market. It’s the rare artist that can hold the course and keep playing the bills and making art. Often, artists stop making art. They become carpenters. They can’t make a living, and most people have to make a living.

Joel: And some of these are artists that galleries would call us up about in the early '90s—it was before images could be sent by email—and they'd say, “We have a painting by this artist. Do you want it? Otherwise we're moving on.” It was shocking. We said, “We don’t do things like that.” They'd say, “Well, I’m sorry," and someone else would buy it like that. Then today, 20 years later, the artist is struggling and their market is cool. And not good cool. A number of the artists who are today being touted as big investments by certain people, we know that in seven or eight years they’ll disappear.

Zöe: It’s very frothy right now, but who can blame some of the people who are buying in. A gallery has the power to sell you a work of art that you and the dealer both know is going to increase in value over the next year or two, and they have to sell it. I mean, why are they representing artists if they’re not going to sell? So when they sell it to somebody they know in fact they are selling money. But only at that moment.

It must be a very confusing time for the artists involved.

Zöe: It’s very hard for an artist in their 20s to keep their head on straight. An artist who is 28 and swept up in this is thinking, "Hey, I’m 28, and I hope I’ll be getting better and better. But why is my work at this huge price? Does it make any sense?" What makes sense is to hold on to your money, kid. I mean, I feel that when an artist is young the work shouldn’t be that expensive, because they can really make a lot of work and have a high energy level. Yes, they should make a really good living out of that, but they shouldn't blow out their prices if they want to have a long career. That’s what Richter managed well. Routinely, Richter’s prices at auction were higher than what he was selling in the gallery until much more recently, when he was an older man in his late 50s and 60s. Then the prices went way up.

What does it mean to you as collectors when an artist you're interested in suddenly has their prices explode?

Zöe: It means we’re unable to continue to buy. We can follow the career, but we can’t buy. You know, we have one Michaël Borremans, but that’s it. Soon after we bought that it became very difficult to continue to buy.

In your home, you display all manner of art in thoughtfully curated arrangements, rehanging the collection each year and unveiling it during your renown open-house tours for Armory Show VIP-card-holders every March. How did that tradition begin?

Zöe: We started showing our collection to the Armory VIPs many years ago as a favor to [former Armory Show co-founding director] Paul Morris , who is a friend of ours. He had this idea that there would be a VIP program with collection visits, and we were very nervous but agreed to do it because it would good for him and the fair.

Joel: People were saying to us, “Are you crazy to have strangers over at your house?”

Back then you were at the vanguard, because these VIP collection tours are now an established practice at many major fairs.

Zöe: What was really surprising was that it went from being a favor for Paul to being something that was really good for us, because we go to think more deeply about our art and try to make a nice show of it as collectors. And it was fun to have people come through and say interesting things about the work that we never thought of.

It must make galleries see you in a positive new light too, because all of a sudden your apartment became a contemporary art museum.

Zöe: Yeah. A little cachè doesn’t hurt when you want to buy work, and they know that because we’re in New York a lot of art-world people will see it.

Joel: We have had a 150 people in three hours during the Armory Show. It's a lot of fun, actually.

Zöe: And some people come back every year.

Joel: But I will tell you that to reinstall everything, wrap it, ship it out, bring in new stuff, and then install it makes for a very tough week and a half.

How do you determine the mix of new acquisitions and older artworks in your collection to show?

Joel: It's never all-new, because there are things that stay, like the Richter. But as for the rest of it, there will be about 25 to 30 things that are new, because we're always acquiring and want to live with the work for a while.

Zöe: It’s emotionally very difficult to take down a painting. We enjoy living with the work—that’s why we bought it—and then, after the year is up, we’re going to not live with it anymore. So we do like to bring things back, like the Shrigley s, which we've been collecting since the '90s.

How many pieces would you say you buy per year, and how many pieces are in your collection overall?

Zöe: Oh, we’re not telling you that. [Laughs]

Joel: That’s dangerous to say exactly. But we have hundreds of pieces. We just donated 161 works of art to a wonderful local museum, which I was told not to reveal. The idea of it is that we just have to deaccession art.

Zöe: We’re not puppies anymore.

What about your son? Does he live with your collection too?

Zöe: Well, he's not an art collector. He certainly has a lot of very nice art in his apartment, which he selected. He said, “How about that one—can I have that?”’

Do you see all of your art eventually going to museums?

Joel: Truth be told, our son will probably sell the art. He’ll keep some things, but the rest of it he’ll sell. And you know something? That’s the way life is. Yet we expect to keep donating art.

Zöe: What's wrong with any of the work being in the private collection of somebody who's enjoying it, really? A lot of it is very lovable work. People come in and relate to it—they would love to own art like that. So, I don’t see anything wrong with the buying and selling. Not everything has to be in a museum.

Joel: We also routinely lend works to shows.

Zöe: We don’t lend to gallery shows, though, because that makes it look like it’s for sale, and we don’t want that. You get phone calls—it’s not pleasant.

Where are you looking for new art today?

Joel: We probably go to at least four to five art fairs a year. Two in New York—which is obvious, because it makes it very easy for us—and then this coming year we’re going to go Frieze and FIAC. End of Frieze, beginning of FIAC. We said, “Paris?” And then we always go to Miami because it's Miami and it’s usually a break from winter, even if it means going there a week after Thanksgiving. Then we have pick other fairs like Turin or Madrid or Mexico City or São Paulo because they have some interesting VIP programs and we like to participate. And, again, it’s a way of seeing a city. But the truth is, we use art fairs more for education than for acquisition, because you can see so much at art fairs. You get sore feet, your eyes feel like they're falling out of your head.

What about galleries? Which programs are you following particularly closely these days?

Joel: Oh, that’s dangerous. We still go to Chelsea, where now there is what I call "Upper Chelsea" and "Lower Chelsea." And on the Lower East side we have three different routes that we can take that cover various galleries. We probably go to 50 galleries a month. We really try to see these galleries if we can, but there are always things in life that interfere, so sometimes we can’t. But the Lower East Side is obviously a wonderful area to explore in terms of galleries if you want to see new artists. And now it's starting to go uptown too, to the Upper East Side.

Zöe: But we don’t want to mention names, because then you wind up offending people. And there are so many good galleries. Although, actually there are many fewer good galleries than there are good artists.

Do you ever work with art advisors?

Zöe: We have friends who are advisors, and we share information.

Joel: But the truth of the matter is that when we started out in the late '70s there was no such thing as art advisors. The art world was a lot smaller, and it would have been hard to understand the concept.

Zöe: There actually were some advisors then—we just were ignorant of the art world. Actually, I think we would have done well to have an advisor early on.

Joel: Instead we were just paging through magazines and saying, “What’s this gallery?" "There's a place called SoHo?” And then we would walk down to SoHo and say, “Wow, this a whole different world down there.” Then we discovered the East Village, and we’d go down on a Sunday, and it was scary. Even during the day. It was still frightening in the '80s.

Zöe: Now people are going out to Bushwick. But who has time to go absolutely everywhere? You always feel like you're missing something somewhere. I think what’s happening now is that a lot of people are really just looking on the Internet. That's a way of seeing a hundred galleries. We look at images, and once you’ve seen work by an artist in person you have a better ability to judge other work of theirs over the Internet. But I must say, we are often given an advance look of a show and we'll like something, and then we'll go in person like another work more. You can’t always tell by images. But there’s nothing wrong with it.

Joel: There are interesting websites that have images from shows in different cities, and then there are galleries that put their entire shows online, so that's all very interesting. And you can see auctions online that you might not go and visit. There’s almost too much information.

How much time do you dedicate to your collection and looking at art?

Joel: A lot, now that we're not working. We probably put 20 to 25 hours a week, on average.

Zöe: It’s easy because there’s a lot of things you do at home—if you're buying something or lending something you have to enter information into a database, because things can go missing. It happens! You have keep track. Let’s say you lend a work to a show, you're assuming that they'll return it, and that the work they return will actually be the one you lent.

Joel: We had an experience where a piece ended up in a warehouse somewhere.

Zöe: I woke up in the middle of the night and said, “What ever happened to X?" It was about three years ago, and we had to track it down to a warehouse.

Joel: Also, we recently acquired a work from a gallery and it was shipped to our storage space, and then the storage space said, “This doesn’t match the image that you sent us.” And it turned out it was the wrong painting.

Zöe: We got a bottle of champagne from the gallery. They apologized profusely.

Collecting clearly occupies a central place in your lives, and you've spoken about how it has encouraged you to travel the world and allowed you to find common ground with people of radically diverse backgrounds. How would you say collecting has colored your lives overall and shaped your experience?

Zöe: I think it has made us closer.

Joel: It gives us something to talk about.

Zöe: Oh, yeah. You sometimes see couples sitting in restaurants and they have nothing to say to each other. We always have things to say to each other. There's no such thing as sitting with nothing to say.

Joel: Now that we’re both retired, it really is an activity that we share and enjoy.

Zöe: It feels like it’s important—like it’s bigger than ourselves. You get a lot of things by buying a work of art that you don’t realize you’re getting. Recognition, and a new thought process.

Joel: Even income. [Laughs]

Zöe: But you also gain access to a broader kind of world that you can relate to, that’s a little bit larger than just yourself. It's like when you're working for a company you believe in, you’re not only making money for yourself, you’re making money for your company. When you have a collection, okay instead of making money, you’re spending money. But it’s your treasure. It’s a very expensive hobby, but it’s important to the galleries that you’re involved. I mean, we get lots of fluffing. So we’re relating to artists, galleries, museums, institutions that depend on us to be there and to be enthusiastic for what they do. It’s a symbiotic relationship, and it's very, very satisfying. It's been great.