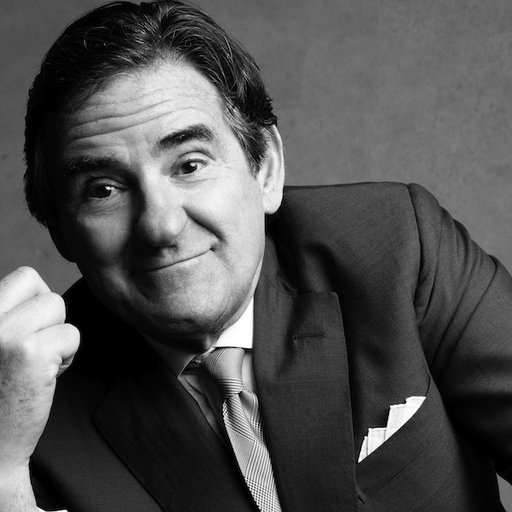

In the relatively genteel sphere of the contemporary art world, the collector Adam Lindemann has caused something of a commotion over the past decade with his swashbuckling approach to the art market, challenging traditional ways of doing business—and often, through his frequent successes, proving himself to be right.

Lindemann is the author of two acclaimed books on collecting, one devoted to contemporary art and the other to design. The latter is a relatively recent passion that he has devoted himself to with zeal, filling his home and office with exceptional pieces by the 20th century's biggest names. He also has penned a column for the New York Observer, in which he likes to tweak meeker sensibilities with nervy pronouncements, such as his semi-famous pledge to boycott Art Basel Miami Beach ("I’m through with it, basta. It’s become … embarrassing") only to hungrily turn up in the same fair's fun-loving aisles immediately thereafter.

Lindemann's most head-turning gambit to date, however, was his decision in 2011 to open Venus Over Manhattan, a raw-walled gallery space on the Upper East Side—in the same building as Gagosian's flagship and Higher Pictures Gallery—that he has devoted to both presenting work by younger emerging artists and presenting expertly curated showcases of famous names like Alexander Calderand Raymond Pettibon. Currently, the space is given over to a show curated by Brooklyn's Journal Gallery, featuring inventive abstractions by Jeff Elrod, Dan McCarthy, Ida Ekblad, Sarah Braman, and other rising stars.

To find out about the thinking behind the show, the gallery, and Lindemann's overall approach to the art business, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein sat down with the collector and former champion polo player in his office, where he was nursing an injured leg from a recent sporting excursion to Alaska.

How did you first become interested in art?

I never really liked art when I was growing up, but when I got out of college I was trying to avoid employment at all costs, and I met a great girl named Cornelia Guest through my brother. We basically spent two years running around together having the time of my life and meeting all these amazing people, and Cornelia's best friend was Andy Warhol. So as a 20-year-old I spent a lot of time with Andy, and I met Jean-Michel [Basquiat], and I knew Factory manager Fred Hughes. We would go to parties and Studio 54, have dinner at Halston’s house with Steve Rubell, Victor Hugo, and all these other people who are now dead. So the art world became this glamorous thing in my mind—these people were celebrities, at least to me—and it seemed like a very appealing lifestyle.

When did you start collecting?

I got into the collecting concept in my thirties really, when I became drawn to things that I wish I had bought when I was twenty—collaboration paintings, and Warhols, and this and that. So I went to the Warhol estate with Jane Holzer, who I had known through Cornelia really, and I started buying some pictures. Then Peter Brant sent me to Julian Schnabel’s studio, and I bought a picture from Julian.

So these were my kind of touch points, and because the art world had this glamorous aura for me—which, of course, I now know is not always the case [laughs]—I wanted to connect to those objects that represented the great time I had as a partying 20-year-old. I think nostalgia has its power.

I have to assume that you also had an intellectual attraction to the artworks too, since, for all its parties, the Warhol scene also had saw some revolutionary ideas being tossed around.

I think it also satisfied a certain personal need that I had. I didn't find exclusively focusing on the business world to be satisfying, so I looked to art to satisfy other appetites for thought and experience. Art brings you a lot of things. Richard Prince once said something funny, like, “Well, what else is there, really?” You know, after you’ve eaten your meals, art generally satisfies this overall need we have to find something more real than the day-to-day grind.

I'd imagine that this need is part of what drives people to compete at places like Christie's for enormously expensive artworks—it's the one thing they don’t already have.

Yeah, well, that’s when it becomes something else—a sort of ultimate trophy: "Look what I have, look what I can buy!"

Now you've not only become a major collector, but you're also an expert on the subject of collecting. You've written two informative and highly regarded guides for Taschen, Collecting Contemporary and Collecting Design.

Well, the thing is, I was never that knowledgeable about these subjects before I wrote the book—I did the books to gain knowledge. The process was almost like a school of my own design, and the book itself actually became my dissertation in a way. I was able to meet all these experts, some of whom I knew but some I didn't know, and I could get their insights. So, let’s say that I bought a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting in 2004 and I was kind of nervous about it. I was able to go to all these different people and ask, “What do you think about Basquiat?” and that would make me feel more confident.

Then, by the end of the project, I'd become a self-appointed expert in a sense, because I was able to speak to all these people that you normally wouldn't have access to—like François Pinault, Larry Gagosian, and Eli Broad—I've put all this information together. And I believe this makes the books a good learning tool for someone who wants to learn about the field, because I'm not talking down to the reader, I'm actually learning along with them. If you want to learn to surf well, you don't go to a great surfer—which is something I tried for many years—because they were born surfing so they can't teach you something they never learned themselves. Instead, if you want to learn how to surf when you're 40 years old, you have to go to somebody who learned later in life, because then they know how to teach it.

Your Collecting Contemporary book came out in 2006, right on the cusp of the art boom. It was very well timed.

Most of the market picks in that book came true in 2007, with the popular fascination with Warhol, Koons, Basquiat, DamienHirst, Murakami, Cattelan, and all those people. If you had only bought the artists that the book said you should, within two years you would have done very well. I was a little bit light on people like Christopher Wool, but he’s still there in the book. And now he's actually risen to be the leader of the post-boom market, commanding insane prices. Meanwhile, some of the art advisors I spoke to have seen their stars rise since the book, and some have fallen.

How did you become interested in collecting design?

At that point, my life had moved around a lot and I was about to furnish my house, so I decided that instead of just buying furnishings it made more sense to buy design that actually had value and could even go up in value. I like markets, and I like the psychology of markets—it’s something that’s interesting to me, as interesting as the things themselves. I'm fascinated by the psychology around these categories, like why people like something, why people pay for something, or why people then hate something.

The design book never really caught on like the art book, which had this kind of zeitgeist moment. The design book came too close to the financial crisis, and also people are just not as interested in design as they are in art. But I still think the book's good. And now I want to do a book on vintage cars. That's what I'm going to start working on this summer.

Have you collected vintage cars in the past?

I had a couple, but I never really got that into it. Now I’m very obsessed with it. It relates to the design field, with cars being these highly designed objects, and I like that aspect of it.

Do you feel that once you start researching a book you become more inclined to buy the work you're writing about?

I always buy what’s in the book.

So, now you are not only a collector and an author but also the proprietor of a gallery, Venus Over Manhattan. How did you go from collecting to being on the other side of the desk at a gallery?

Well, I was in the radio business, and then I sold it all in 2007, and in 2008 it closed. I thought, what have I been doing other than focusing on my business? I had been focusing on collecting, and I always liked to buy art, and I also liked to sell it. I didn't like the idea of just owning something for life—it didn't appeal to me. But I love the market for art. And so I did the collecting thing, and then I did the writing thing, satisfying that with the books and writing in the New York Observer, and then I reached a point where I realized that the one thing I haven't done is opening a gallery and mounting exhibitions. For a while I thought very hard about the foundation model, and I was going to do this as a foundation, but then I decided that model wasn't for me. Foundations were for people of a prior generation to me, who, you know, might create a foundation but then eventually have the work find its way into the market anyway. I don't like hypocrisy.

Like Adam Sender, who recently sold off much of his foundation through Sotheby's.

That wasn’t for me. I just thought, okay, I’ll do exactly what people don’t want me to do: I’ll open a gallery. Everyone was uncomfortable with the concept of the collector becoming the dealer, but I really don’t see myself as being any different than I was before.

Obviously you had insight into the inner runnings of a gallery, not only through your collecting but through your marriage to Amalia Dayan, the former Gagosian dealer who opened the Upper East Side gallery Luxembourg & Dayan with Daniella Luxembourg. What did she think about starting Venus Over Manhattan?

She didn't want to me to open a gallery either—she was very against it, as was her partner and all of our friends. And all of our artist friends, and the curators too. They were unanimously against it. The collectors and dealers don’t like it, either. Nobody likes it.

It seems they have changed their tune since your gallery opened, because the shows have been of a very high quality, and the openings are always thronged with a VIP crowd of artists, curators, collectors, and other tastemakers. What happened?

Well, they got over it. [Laughs]

What do you think explains their initial opposition?

Each person has their own reasons, but generally speaking, just to put it very politely, galleries are organic things that are well looked-upon and digested by the system when they grow from a very small seed over a long period of time, after many years of hard work. I’ve certainly appreciated how hard the dealers work from my experience here—you don’t really understand it until you actually have to roll up your sleeves and do it yourself. It’s like the Wizard of Oz—you see the big wizard on the wall and then you go behind the curtain and realize it’s just a little old man talking into a microphone.

So the main reason they didn't like it is that I didn't take the normal gallery path. David Zwirner has been open for 20 years—he’s basically my age, but he’s been doing this for two decades. Larry Gagosian has been open for 35 years. Amalia has been an art dealer her entire life—she’s never been anything but an art dealer. She didn’t produce a movie, she didn’t work on Wall Street, she wasn’t an arbitrage trader, she didn’t run a radio company or go to Law school. She’s always been an art dealer.

With me, a very established dealer friend of ours said to me when I complained that our shows weren't getting any reviews: “Well, come on, what do you expect? You just dropped in from outer space.” In the art world, it was frowned upon for me to just to open up shop as usual. The only person who has been in my position is Bobby Mnuchin.

As a heavyweight Goldman Sachs trader and collector who opened L&M Arts and then recently spun off into this own gallery, Robert Mnuchin obviously made it work. But it’s funny to think that the art world is thought of as being so liberal and cosmopolitan, but at the same time there are so many unspoken rules, almost like sumptuary laws. If you step out of your station, you can be harshly criticized.

Collectors need to be collectors. Dealers need to be dealers. Artists need to be artists. Artists can’t deal. Collectors can’t deal. Dealers can’t collect. But, of course, everyone is doing everything, but you’re not supposed to, or at least you’re not supposed to do it openly. But I still collect. I don’t collect that much anymore, I have to say—my primary focus is doing the shows. Now I want to try to do more shows, and grow this gallery, and participate in art fairs. It’s certainly slowed my collection down to a snail’s pace.

So if I'm a collector and I come to the gallery to buy a painting, do you yourself sell me the painting? Who handles the dealing part of the business?

Well, I’ve sold some things here, but we have a really great staff, and I’ve found it better in this situation to work as a team rather than always be the front man. I’m happy to be in the background.

How would you describe your clientele? Are they the same collectors who go down the hall to Higher Pictures, and upstairs to Gagosian?

I think in our case we have not yet developed what I would call a regular clientele, which is also something that has to grow organically. If you’ve worked at Christies for 10 years and you leave, then you have those client relationships. I just popped open, so I don’t have any regular clientele. I sell to dealers—they're my main clients—and after dealers I sell to consultants. And then many of my collectors are artists. So that’s who I’ve sold to, because I sell to people who know what they're doing—I don’t need to take them through or hold their hand. But now our team is starting to gain a clientele that’s being developed through the gallery.

At the moment you don't represent artists, which is one way that a gallery builds an organic collector base. Will you ever have your own stable of artists?

I think it’s very hard at this point in the art cycle to pop up and get the kind of artists that I would want. This is our third year, so I would love to represent artists, but it would have to be the right combination. Alternatively, we could go very young, and I've shown some very young artists here, as I did the Charles Harlan show with Jasmine at JTT and Andra Ursuta with Ramiken Crucible and Peter Coffin. Those were all primary-market shows.

But the artist representation model is a little bit archaic in my view. I thought it was going to break down about four years ago, and yet galleries still keep it going. I think it’s not necessarily always the best model for the artist, though in some instances it is. But I think we'll do it if the right opportunity comes around. Per [Skarstedt] was secondary-market dealer until he joined up with George Condo, and now he’s showing Lucien Smith, so good for him. And Larry was always a secondary-market dealer—he only set up this primary-market operation in the second stage of his business.

Do you see the gallery as a project you intend to remain committed to for years and years going forward? I read somewhere that you had a ten-year window for Venus Over Manhattan and then you would decide whether to keep it going, but it sounds like you're looking at it as being more on a long-term growth model.

I think so. I have a 10-year lease, so I like to say, "Two years down, eight more years to go." It's a bit of a marathon, though I think we’ve had a lot of quick positive results, which is a good sign. I think that there are some realities of organic growth. Let’s see if after 10 years I do 10 more.

For your current summer show, in the latest of your collaborations with emerging galleries, you've made the welcome decision to devote your space to the Journal, the excellent Brooklyn gallery and publication founded by Michael Nevin. They've built a reputation for working with very young artists and minting overnight stars, like Eddie Martinez and Graham Collins. How did you first come to meet Michael Nevin, and how did the idea for this show come into being?

Anna Furney, who works with me, really likes them—she likes the vibe, the atmosphere, the energy, and also their parties. So it had a positive connection for me, and I pitched the idea to them because I thought it would bring this younger, hipper Brooklyn energy to Madison Avenue, where it doesn't belong. I liked the idea that we could attract those people here, and that they have this different fabric of artists that they work with and we could bring here.

It's actually the third time we’ve given up the space for a summer show. The first time we gave it to Matthew Higgs for his "Bulletin Boards" show, and the second time was with Gavin Brown for the group show Laura Owens and her friend Peter Harkawik curated of Californian artists. With the Journal, what I wanted out of it was energy, and he delivered a lot of energy—we had a great party, we had great opening, and we had a lot of people.

Even artists like Sam Moyer came, so I got to meet her and chat with her and her dealer, Rachel Uffner. We collaborate and everyone wants Sam's work, so we get to move her work to people who want to follow Sam. Then I learned that Sam is actually married to Eddie Martinez, which I didn't know, and he’s also in the show, so there was just a nice feeling about the whole thing. There's better chemistry than if we just did the typical summer show, which is like okay, let’s just pick 10 artists that we're not really sure about and just throw them together and see what happens. As far as I’m concerned, the art world slows down after auction week anyway.

How do these shows that you do with younger galleries sell?

Certainly the sales we have here are sales that the Journal perhaps otherwise would not have, we're happy to help them in that way. The Charles Harlan show I did was good for Jasmine, too. And everything in the Andra Ursuta show we did with Ramiken sold, so that was good for Andra and for Ramiken. So I think our projects here are help the artists and their galleries, but some people are cynical and say, "They’re just trying to turn the art into money.” Well, I have nothing against money. I like money. I love to spend money, and it’s good to earn money. But we also try to do projects that are curatorial or even exploratory.

We can put a young artist here, and we get to see how good their work is and what it means. It was interesting to me to put Charles Harlan in our space during the Armory Show and just have it be a big fence, because an art fair is when everyone is showing objects you can buy in little cubicles and we were showing one huge thing that no one could buy. I thought it was an interesting juxtaposition. It was a statement piece, and it’s good to be able to do that.

Speaking of curated shows, the gallery entered the spotlight with its first curated show in a rather unexpected way with the freakish theft of a Salvador Dalí drawing from "À Rebours," an exhibition inspired by Joris-Karl Huysmans's 19th-century novel of aesthetic decadence. Can you walk through what happened there, exactly?

Well, my shows are usually dark—you always know it's my show if the lights are off. The Calder show was in the dark, the Jack Goldstein show was in the dark, and "À Rebours" was in the dark. So this guy just walked in, literally lifted my Dalí drawing off the wall, put it in his black bag, and walked past the security guard and out the door.

How did you find out about it?

Someone here in the gallery ran in and said, “The Dalí’s missing!” I ran outside, where we had done this salon-style hanging of all these really interesting pieces, and the Dalí was missing. I had two Dalí’s in the show, and the guy stole the unsold one, which was good because I didn’t have to make an excuse to the people who bought the other one. But I was just in shock. The police came immediately, and then next thing you know there are TV cameras in front of the gallery.

Uncharacteristically, I didn’t give an interview, because I was afraid of what would happen—I was really afraid that no one would ever lend to me again because we had a theft. I subsequently found out that many people have had thefts and it's not that unusual. But, in any case, some time went by and then we received a weird email from an anonymous email address that the work was going to be sent back to us, rolled up in a tube, from Greece of all places, and it supplied a tracking number.

I called the police and I told them that I wouldn’t accept it because I just didn’t want to touch it—I didn’t know where it’s been, I didn’t know what was going on with it. I told them, "Here’s the tracking number—you deal with it, you fingerprint it, you examine it." Because it was a work by Dalí, it wasn't an insignificant thing. So they pulled it out of the express mail and found that it had the same fingerprints of a guy who had shoplifted at Whole Foods three or four years ago. And they knew who he was—he was the head of PR at Moncler, working out of Milan. A Greek guy.

Named Phivos Istavrioglou. What happened next?

They emailed him at Moncler in Milan and said, “Please come to New York, we’re looking for someone to handle PR at an art gallery.” They created a sham art job and sent him a plane ticket to come to New York for an interview, and as he landed in Kennedy they handcuffed him. Afterwards, Maurizio Cattelan texted me and said, “You must have invented this—it’s just way too good.” When asked why he stole the piece, he just said something like, “Because I could.” Which is very much in the spirit of the Duc Jean des Esseintes, the protagonist of À Rebours, who was this noble, aristocratic, art-collecting delinquent.

He throws away his inheritance, he acts inappropriately, he’s morally debauched, he does everything wrong. This thief reminded me of that, because he didn't need to steal things—he was like one of those people with diamond rings all over their fingers who go to the supermarket and put popcorn in their pocket or something. It's a kind of 19th-century, Romantic, delinquent, aristocratic behavior.

Well, you’re obviously a very good curator, if even the theft matched the curatorial theme.

It was so cool! [Laughs] It was great, and I thank him for that. I was very hopeful that we wouldn’t have to prosecute him, because while I don’t encourage thievery and I don’t want people to come here and steal things, I thought prosecution would be bad karma for us—after all, everything is fully accounted for, the work was fully insured, and we knew who the guy was. I just didn’t want to be involved in that kind of negative experience with my first show. So the head of the police department gave a press conference, announcing, “We found the guy!” But I think in the end they just slapped him with a fine and let him go. In a way, I think it’s a wonderful story to have.

To go back to the topic of collecting, another breed of ostensible malefactor that is getting a lot of attention these days is the flipper, the kind of collector—popularly personified by Stefan Simchowitz—who buys young art cheaply and then sells it for huge returns, often multiples of the original price. A website called SellYouLater, now ArtRank, has emerged to cater to this audience's day-trading sensibility.

I love SellYouLater. I love Simchowitz.

My question for you is: is this really a new financialized form of collecting, or is it a time-honored method of profiteering off art that has simply been made more transparent, or gone viral, because of the Internet?

Well, you can just go back to the famous story of the Sculls. I've studied them, and it's so amazing that this taxi-fleet owner was able to own all these Rauschenbergs and Jasper Johnses and then eventually flip the whole thing at auction for $10 million. In the end, Robert Scull lost all the money in the divorce and ended up bankrupt, and his wife had nothing either. And, in retrospect, if they had kept all of the art they flipped for what seemed like a lot of money, it would probably be about $1 billion. So forget what they made—think of all the money they lost. But the famous story is that, at the auction, Robert Rauschenberg went to Bob Scull and said, “You bastard, you flipped my work,” and Bob Scull said to Rauschenberg, “Bob, it was good for you too.” Because he did set a record.

So, I think that there is a lot of disingenuous agendas at play when it comes to flipping. Nobody wants to say they’re in favor of flipping, but actually the artists are quite flattered when their pieces make a lot of money. Each situation is a little bit different, though. I think it’s quasi-tragic that Allen Jones furniture from the '60s and early '70s makes millions of dollars at auction, but the real Allen Jones is living in London and having a hard time. He doesn’t get any of that money, and it’s hard for him. There's some unfairness in this, and, of course, if everyone flips, then the whole art market collapses—which is the sort of fun of SellYouLater.com.

I’ve been accused of flipping things, and I certainly have sold things at auction from time to time. I think if you occasionally sell, and you sell the right thing at the right time, there’s nothing the matter with making money. I think if you sell everything you own, that’s a whole different thing—then we've lost the whole reason that we became interested in art in the first place. We’re interested in art because it gives us something, and if it’s just a financial commodity to churn and make other people speculate in this game of musical chairs, I find that tedious, and I’m not that interested in that. So, all of the names that might be hot on these lists are not that appealing to me. Now that I’ve opened my own gallery, we try to avoid that stuff.

With that said, you know, this is the zeitgeist. Look how many people are in the art market to speculate—everyone’s a gambler, everybody’s a wise guy now. And I think that even if the high end of the market slows down—and the middle of the market has already slowed down— the speculator stuff is going to keep going. Because this is like going to the racetrack, or going to Las Vegas. Everybody wants in on this. I’m shocked at how much money people pay for artists that haven’t even shown yet just on the rumor that they're going to such-and-such gallery, or somebody might pick them up. I mean, it’s really amazing, and I think it’s definitely here to stay. And it’s growing.

When it comes to flipping, you yourself carried off a spectacular coup of reselling on at least one occasion, when you bought Jeff Koons's Hanging Heart (Magenta/Gold) from Gagosian in 2006 and then sold it at Sotheby's in 2007 for a then-record $23.6 million—to Larry Gagosian.

I bought it for $1.6 million, and it became the world record for living artist at the time. But Larry bought it on behalf of a client, an oligarch.

What happened there?

You know, I’m a big fan of Jeff Koons—I love Jeff’s work, there's a kind of magic to it for me, and I’m a buyer of his work. I have a few pieces in my collection, luckily. But with this particular opportunity, there was suddenly a stratospherically exponential reappraisal of what these "Celebration" series pieces were worth. So I just thought, “Well, the sale of this one piece of art in my collection allows me to do a lot of other things.”

And I’ve known Larry for a very long time, and I have tremendous respect for him—he’s amazing. But Larry was upset, I remember, so we had a conversation. I’m a big supporter of Jeff’s, and Jeff knows that, and I’ve been a good client of Larry’s over the years, and I still am. And, you know, that price re-priced the whole "Celebration" series—what I saw was a fraction of what the gallery and the artist saw, because based on that $24 million sale the price of every "Celebration" piece and every "Celebration" piece subsequently made jumped almost 20 times in value.

It was a historic event.

It’s an amazing sculpture, and I had the best color. The thing was that my wife was working for Larry at the time. But what people don’t remember is that nobody was buying those pieces.

Jeffrey Deitch was famously bankrupted by the fabrication costs before Gagosian took Koons over, and then buyers had to take over those costs, right?

You were investing money in something that didn’t yet exist, and people are opposed to that. They tried hundreds of collectors and nobody would put money up for that because the dealer had gone bankrupt the last time around. So it was a pretty risky thing to do. But I paid for the production of it, same as with Urs Fischer’s Teddy Bear, same with Franz West's The Ego and the Id, same with a lot of things. The dealer either doesn’t have the money or doesn’t want to finance the piece, so the collector comes in and supplies the money.

It's amazing how much money is being put into art these days, and when one looks around and sees all the younger artists who are making very similar things, and yet they're all successful, it might lead some people to suspect a bubble.

I don’t like that. Who needs all this stuff? I mean, this is crazy. No one needs any of this stuff. It’s unbelievable. And it doesn’t go on people’s walls, it goes to auctions, it goes in storage bins. But as for everyone being successful, I think there's a lot of smoke and a lot less reality to that. In the broader scheme of things, we’re not talking about large amounts of money. If you buy something for $10,000 and you sell it for $50,000 or $100,000, okay, that will buy you a sports car. I won’t say it’s insignificant, but no one talks about the 25 other paintings they bought for $10,000 that are worthless. It’s about hitting a winner, it’s not really about counting your losers. And I think that while so many collectors are very excited by paper profits, they under-appreciate how much harder it is to sell than to buy. It’s not so easy to sell art—we work very hard here to sell the art.

It seems like in the auctions, which you closely observe, there’s a capacity for these younger artists to have their prices vastly inflated by interested parties. The rumor is that there were only two bidders for the first couple of Oscar Murillos that brought his value up to $400,000, and in such a case it could have conceivably been the same two people with large holdings of Murillo's work simply enriching themselves. Or is there more transparency than it seems?

An auction is just a theatrical sale of an object that allows the possibility of other people coming into bid. Often, especially in a guaranteed situation, the work is already pre-sold and they're just passing it in front of a stage to show people what’s already been sold and ask if anyone in the room or on the phone wants to pay more. So are these markets for young artists real? I can't say—and it definitely would makes sense for someone who owns 50 paintings by an artist to buy one more for a high price.

But what I will say is that this was the case with Basquiat and Warhol, too. People always said that the Warhol market was only where it was because it was being manipulated by parties with large inventories of Warhol, but look what happened. Now it’s stuck to the ceiling and it’s not coming off. It was the same with Basquiat—it was always, “Oh, Basquiat always sells because these people bid on him, and without that his prices wouldn’t be there.” Well, you might try to unravel a ball of twine, but it’s still a ball, and it’s rolling, and no one’s going to stop it.

So, you don't see this as a sign of an inflated market, but the opposite?

In fact, when I look at a situation like this with many interested parties, dealers or investors, those vested interest will actually protect the market. That's the safety net. So if those people have 30, 40 artworks by an artist and they’re putting their hand up at auction, that’s what I call safety, because without those guys there might be nobody to buy on a given day. In the design world, look at the Prouvé market. You know, the Prouvé market is the safest in the furniture market, and the reason is you always have four dealers who are willing to raise their hand in the room—you have Patrick Seguin, you have Jean Royère, you have Philippe Jousse, and you have Francois Laffanour. If this desk [gestures at his Prouvé desk] ever showed up at auction in a liquidation sale, those three guys are going to buy it. They'll never let this desk fall below a certain value. So, if people say, “The Prouvé market is just manipulated," well, these dealers are putting their money where their mouth is. And if that is the case with someone like Oscar Murillo, I would say that’s a bullish sign.

Take the George Condo market for example. I love George and I think he's a great painter and a wonderful guy, one of the real New York characters. But his market was so soft. Then you had people buying it at auction, and the price moved, and now it’s stuck—now it’s real. That’s the price of a George Condo, and you won’t get one for less. Sometimes these things are apparently manipulated, but actually those are the stronger things. The myth is that there's always someone for a painting at any time in an auction, but how do you know that Tuesday, November 14th, at 8:30 p.m. someone will be there to buy a particular Andy Warhol? You want to be in a situation as a collector where you know there is five or 10 dealers out there who will all buy for inventory at a certain level—that's what create a strong market.

A much-bemoaned development in the art world is that, while the bluest-chip galleries are thriving and the youngest ones are selling out shows by emerging artists, the middle tier galleries showing mid-career artists are struggling in the grips of an existential crisis, and frequently closing. For non-speculators, this is a troubling phenomenon, because it poses a challenge for artists to have careers that stretch over time—the middle seems to be falling out. Is this something that concerns you?

It's less than you think, and I believe it's a sign that we’re reaching a mature phase in the art market. There was a very strong growth phase during the time I wrote the book, which was coming out of the art crisis of the late '90s where dealers were just giving art away. Back then, the Nahmads were buying up Picassos, and Mirós, and Calders and Jose Mugrabi was buying up Basquiats and Warhols, and everybody who bought those things just had unbelievable returns, and everything else that they did after that is just chicken feed because they were there and hoovered up names that are huge at the right time. The biggest markets in the art market.

So that was the growth phase, the decade from 2000 up to now, with that blip of the crisis in 2009, and it re-priced art as an asset class in my view. Meaning, Warhol will never be cheap again. Basquiat will never be cheap again. Giacometti will never be cheap. Christopher Wool could go down from $25 million, but it will never be cheap again. There will always be someone who will try to buy it, because the whole asset class has been re-priced.

Now we’re entering a stage where the art market is much more mature and efficient, so it’s natural that the biggest players will continue to be big. There’s always room for the little grassroots players, but if you didn’t grow in that growth period into one of the big players, well, then you’re left behind. So, I think that those middle-sized galleries will continue to struggle unless they have a strong artist that they’re tight with—it only takes a strong, core relationship with one artist to make a whole gallery, and all the other stuff is just filler.

Where does that leave Venus Over Manhattan?

It's not easy to find room in this system. I've often said that opening a gallery in New York City is like opening a pizzeria. Do we really need another slice of pizza? There’s one on every street corner. That’s why I always felt that our programing has to have an unexpected, personalized, independent voice. Each show is doing something a little different from what’s been done before. The Jack Goldstein show was done in the dark, and we were playing Patsy Cline, and we had an essay by Ashley Bickerton, so it had a whole ambience. With the Calder show, I mean, who the hell needs another Calder show? Pace does great Calder shows, the Nahmads have done great Calder shows, lots of people have done great Calder shows. But no one did one of Calder’s shadows. So we’re always trying to challenge ourselves to come up with a new recipe, and I think it’s that challenge that makes this exciting and worthwhile.

Last question: in all your years of collecting, what's the one that got away?

I wish I had Andy paint my portrait. He offered me a portrait, and it was about $20,000. I was 21, and it just didn’t occur to me. Andy took my picture though, and I got my picture from Tim Hunt at the estate. But I do regret that I didn’t get my portrait—that would be a nice thing to have.