Depending on our religious beliefs – or lack thereof – we might claim that a large portion of humanity’s total artistic output has been concerned with the supernatural. After all, for the atheist what unites the classical Greek sculptor Leochares’ marble the Apollo Belvedere, Raphael’s painting The Transfiguration of Christ (1516-20), and the famous Chola-period bronze of Shiva Nataraja in the British Museum is that each of them depicts a supposedly superpowered being who does not – and could not – exist.

And yet, for their makers these works did not constitute depictions of the paranormal. Rather, they were images of the natural order – of the world as the artists believed it was and should be.

‘Supernatural’, then, is a tricky and highly culturally specific term. In the West, it’s often used to refer to a set of entities that the Bible identifies as uncanny or outright malevolent (ghosts, demons, witches), augmented by creatures such as vampires and werewolves that, while they are not mentioned in scripture, have deep roots in European folklore. Such figures appear time and again in great works of art, from Francisco de Goya’s painting Witches’ Sabbath (1798) to Henry Fuseli’s canvas The Nightmare (1781), from Andy Warhol’s screen-prints of Dracula to Mike Kelley’s superlative multimedia installation Day is Done (2005), in which the late artist adopted the role of the devil himself.

Today, such paranormal beings are more likely to inspire a spook-tacular Halloween costume than genuine chills, and it’s in honor of this upcoming festival that we bring together six works by contemporary artists that respond to all things weird and eerie. But if in the 21st century rational empiricism has (just about) replaced a belief in ghouls and goblins, then as these artworks demonstrate, the notion of the supernatural still has much to teach us about the dark underbelly of our culture, and our own, shadowy psyches.

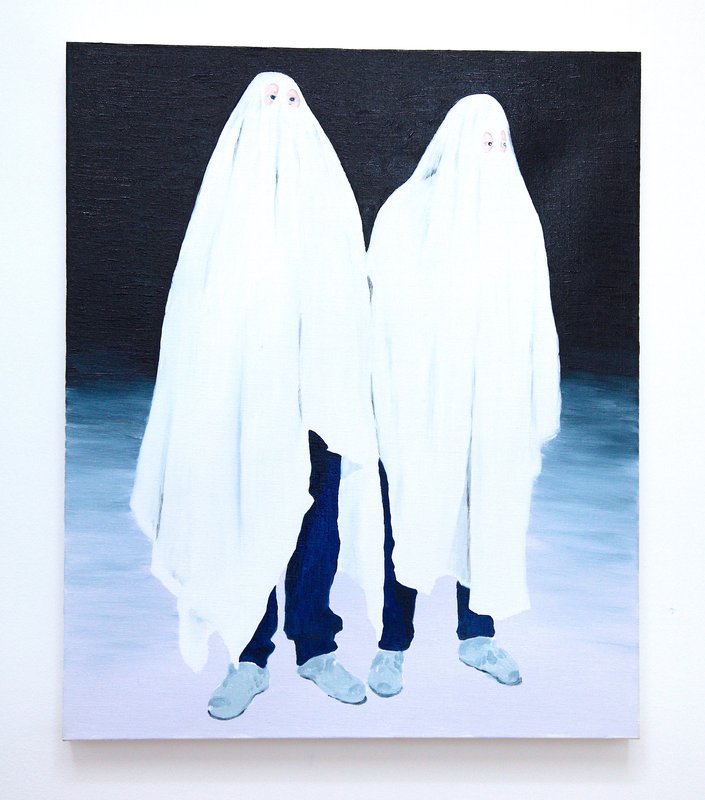

JAMES RIELLY - Ghosts working with fears and inhibitions (2017)

Depictions of ghosts as anthropomorphic billows of white fabric have their origin in early modern European burial practices, which saw the bodies of the deceased wrapped in a shroud or “winding cloth”. Fast forward to 1904, and M.R. James publishes his classic (and still terrifying) ghost story Oh Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad, which features a bedsheet animated by an invisible, malevolent force, inspiring generations of children celebrating Halloween to cut eyeholes in their mothers’ best linen, and take to the streets demanding candy with menaces.

In the noted British painter James Rielly’s canvas Ghosts working with fears and inhibitions, we see two such trick or treating kiddies. The artist pictures them as though they are standing in front of a house, just about to ring its doorbell, the dark of a late October night at their backs. Through the peep holes in their bedsheets, their eyes look wary, ready to flee, as though what’s really frightening, here, is not their homemade costumes, but the unknown grown-up who will answer the door. To whom do the painting’s titular “fears and inhibitions” belong, and how precisely are these boys “working with” them? Perhaps what really spooks this roleplaying pair is the prospect of leaving childish things behind, stepping over the threshold of adolescence into adult life, and onwards towards inevitable death.

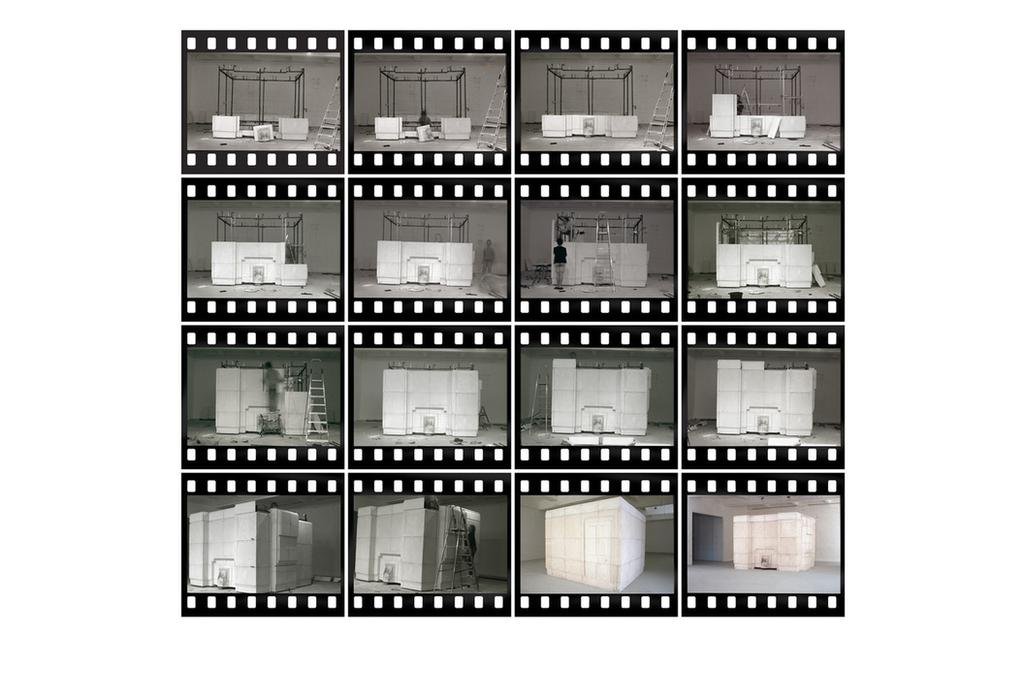

RACHEL WHITEREAD - Installation of Ghost (1990-2012)

A ghost is, by definition, something that once knew life. By this logic, might we speak not only of the ghosts of human beings, but also of the ghosts of the places they once inhabited? This question was at the heart of the leading British sculptor Rachel Whiteread’s breakthrough work Ghost (1990), which saw the artist make a plaster cast of the interior “void” of the parlor room of a North London Victorian house. As the contact sheet-like series of photographic images documenting the creation of this sculpture indicates, the result was an eerie transubstantiation of negative space into positive form, of the intangible into the tangible.

Whiteread has said of Ghost that she was trying to “mummify the air” in this 19th century interior. Notably, the artist did not cast a room in a famous historical building to make her sculpture – the site, say, of a notorious murder – but rather one in the kind of house occupied by tens of thousands of contemporary Londoners. When such properties change hands, the first thing the new owners usually do is attempt to banish the spectre of their homes’ previous inhabitants by redecorating. Fresh wallpaper and soft furnishings, however, are at best unreliable forms of exorcism. As Whiteread suggests, to live in an old house is to live alongside its ghosts.

CINDY SHERMAN - Witch (1986/1993)

The witch is a profoundly ambiguous figure in Western folklore. She might heal or hex, present as a young maiden or an aged crone, acquire her supernatural powers from a deep communion with Nature or by doing a deal with Beelzebub. From the witch trials of the 17th century to 21st century American high schools banning teenage girls from wearing Wiccan pendants, what remains constant is that she inspires a mixture of fascination and (often misogynistic) fear.

Widely regarded as one of the world’s most significant living artists, Cindy Sherman is best known for her photographic self-portraits, in which she adopts various guises to probe (and subvert) the visual brokering of female identity. Made during an audacious period in her working life when she turned from the cool precision of her celebrated Untitled Film Stills (1977-80) towards the unruly and the grotesque, Witch sees the artist don a fright mask and a pair of rubber gloves – and index of either everyday domestic labor, or of a bloody clean-up job following some undisclosed nightmarish act. And yet it is not the character’s costume but her pose that makes this work so uniquely unsettling. Resting her chin in her hand, she meditates on something beyond our ken. Perhaps this witch is plotting the murder of a princess with a poisoned apple, or perhaps she is simply summoning the energy to do the washing up.

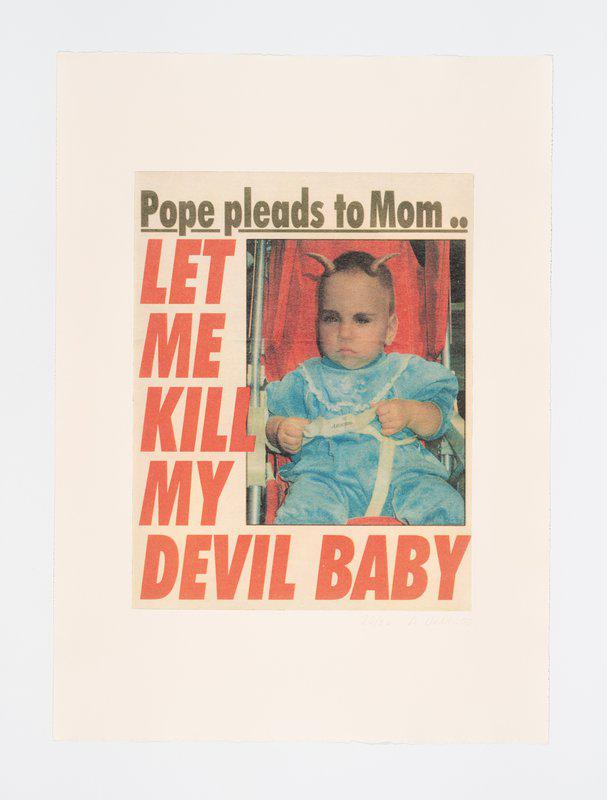

ALBERT OEHLEN - Let me kill a devil baby (2000)

The New Testament is pretty vague as to what point in human history the Antichrist will appear, and how he will manifest. Perhaps the most detail is given in the Second Epistle of the Thessalonians, which warns that this “lawless one” will employ “all power, signs, lying wonders and every kind of wicked deception” to further his evil ends. Such imprecision is perhaps designed to keep the faithful on their toes. If the Antichrist might pop up at any moment, and in any guise, then the only reasonable response is unceasing vigilance.

In this print by Albert Oehlen, the seminal German painter seems to take his cue from Richard Donner’s 1976 classic horror movie The Omen, in which the Antichrist takes the form of a baby boy. Unlike in the film, however, Oehlen’s satanic infant’s dad, is not an American diplomat, but (according to the tabloid headline that runs across the top of the work) no other than the Pope, God’s representative on Earth. It appears that the supposedly celibate pontiff has fathered a child, and having noted its demonic horns and red, pitiless eyes is now desperately contemplating infanticide, his first sin begetting another. And yet, if Oehlen is satirizing incontinent red top journalism and the hypocrisies of the Roman Catholic Church, he’s also taking a knowing swipe at one of the gods of the German art world. The baby’s onesie is embroidered with the word “Anselm” – the first name of Oehlen’s contemporary, the celebrated painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer.

MONSTER CHETWYND - Bat Opera 187 & 188 (2014)

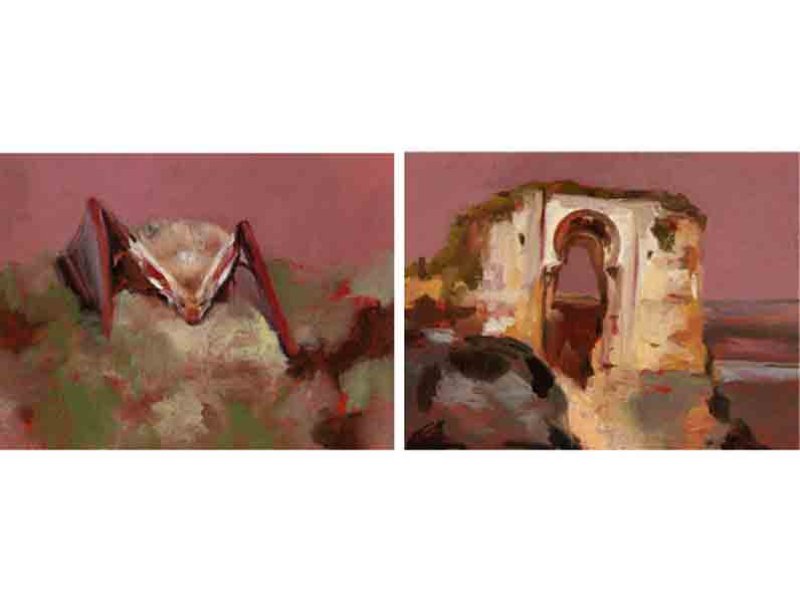

Since 2002, the Turner Prize-nominated artist Monster Chetwynd (who formerly rejoiced in the increasingly unlikely forenames Lali, Spartacus and Marvin Gaye) has been producing paintings for her ongoing series Bat Opera. Of these works, Chetwynd has said that “I am always interested in culture that is thrilling but that is somehow undersold. Underdogs, stories that could do with celebrating or rehabilitating. Bats fit into this, they are so extraordinary and varied. They pollinate [crops] at night, they have radar, they are mammals with wings and, of course, they have the stigma of evil. They are perfect as unworthy subject matter.”

In this lithographic diptych, Chetwynd serves up an image of one of these eldritch beasties and of the gothic ruin where it roosts – a member of the cast of her notional opera and the backdrop against which it sings. What might this performance sound like? Most bat echolocation occurs beyond the range of human hearing (while we can hear between from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, bat calls range from 9 Hz to 200 kHz), so it follows that whatever Chetwynd’s rodents are singing about will remain a mystery to a homo sapiens audience. We are left to contemplate their furry, demonic faces, our thoughts turning to the veins that throb in our fleshy, vulnerable necks.

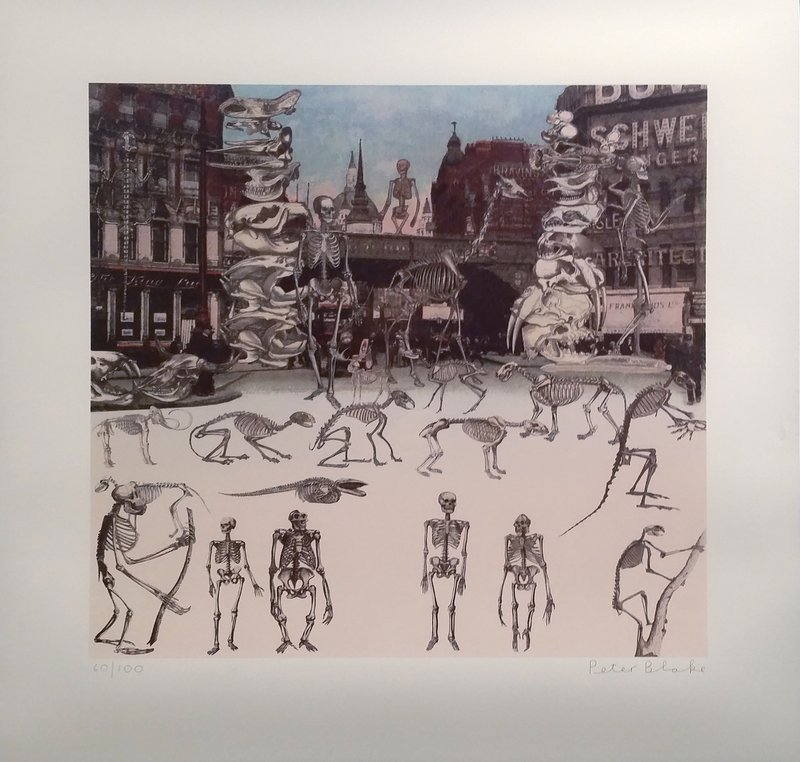

PETER BLAKE - Ludgate Circus – Day of the Skeletons (2012)

Universally known for his cover for The Beatles’ legendary 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – which featured images of the occultist Aleister Crowley and the horror writer Edgar Allen Poe among its pictorial rollcall of (in)famous figures – Sir Peter Blake is a towering figure in British Pop Art. In this recent print, he turns his attention to one of London’s oldest locations, Ludgate, which connects Westminster and the City, and is named after the possibly mythic pre-Roman King Lud, who according to Geoffrey of Monmoth’s Historia Regum Britanniae was the founder of the British capital. This is a place, then, with a long history, but as Blake shows in his silkscreen, the past does not always stay buried. Given half a chance, it will rise from the grave, and rattle its restless bones.

The skeletal figures that stride about this image of contemporary Ludgate Circus are not, we should note, all homo sapiens. In addition to the bony remains of various prehistoric quadrupeds (giant elks, mammoths, sabre-toothed cats) we also see those of several species of early hominoids – our direct evolutionary ancestors. What has caused them to awake from their slumber beneath this busy traffic intersection? Perhaps, as Blake’s title suggests, they are involved in a post-Darwin version of the Mexican Day of the Dead, a festival during which the spirits of the deceased are said to visit the living. If so, what business might the resurrected skeletons of proto-humans have in London’s nearby financial district? Will they tear down its gleaming towers, appalled at how their descendants have replaced hunter-gathering with hyper-capitalism, or will they stroll into the HQ of a major investment bank and apply for a job?