Women’s Equality Day is one of the longest-standing calendar dates celebrating female emancipation. Started in 1972 (and designated a year later by Congress), it marks the day in 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment was adopted by the US Constitution. This prohibited states and the federal government from denying citizens the right to vote on the basis of their gender.

This year marks the centenary of the Amendment, at a time when questions over individual rights versus the state, identity, representation and the power of protest are more contested than at any time in recent memory.

And this is as true in the art world and creative industries as any other field: in the past 12 months New Orleans Museum of Art was accused by its own staff in an open letter of propagating ‘a plantation-like culture behind it’s facade’ and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s senior curator Gary Garrels resigned after employees petitioned for him to go following comments relating to the museum’s acquisition policy. Meanwhile, workers at London’s Tate and Southbank Centre are protesting job cuts which they claim are disproportionately hitting minority workers. The world famous Magnum photo agency is currently examining its archive following a series of storms over the makeup of its board and the nature of some of the work it hosts.

Multiple galleries are struggling with the issues raised by their own collections, boards, acquisition policies and exhibition programmes . Resolving these issues is going to involve a process and an evolution, not just one event or inquiry. However, it’s still worth celebrating that these conversations are taking place publicly, that pressure is being applied and that work that was previously overlooked is now taking priority. In that spirit, here are five of our favourite pieces from Artspace for Women’s Equality Day.

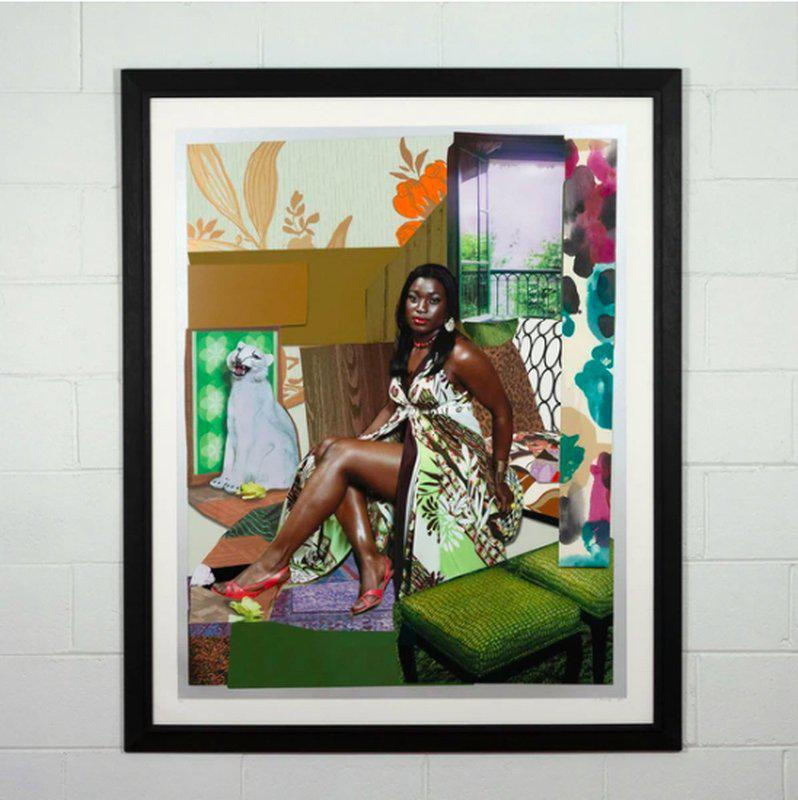

I Have Been Good To Me, 2015 - Mickalene Thomas

Thomas is one of the most significant figures working in American painting right now. Her route into art came via early study in photography, moving family home as drugs and imprisonment plagued her mother and stepfather, relocating to Portland after high school partly to shake off homophobic family members and an early career in law. Her turning point was seeing an exhibition by the African American artist Carrie Mae Weems: “It was probably the first time I ever saw myself in art,” she said. “Those photographs really hit the core. I felt, that’s what you can do with art? Wow. One day after I went to see the show on my own, I didn’t even think about it, I just walked to the art-supply store.”

Since then, her work has gone on a deep dive into colour, texture, representation and the historic role of black women in western art (most famously, she reconstructed Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe with confident, and fully clothed, black women – the painting ended up in New York’s Museum of Modern Art). Her work has got bigger, multi-layered, and experimented with texture, oil paint being augmented with shining lumps of rhinestone and sequins. As well as her painting, she’s worked with photography, video art and mixed media prints, like this piece from 2015, which includes screenprint, monoprint, silica flocking, wood veneer and digital printing and comes in a signed, dated edition of 20.

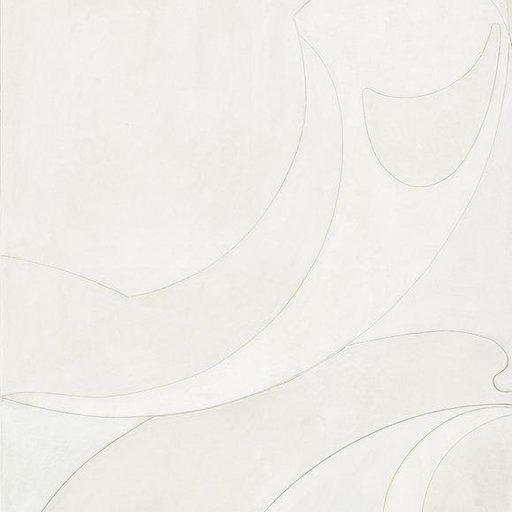

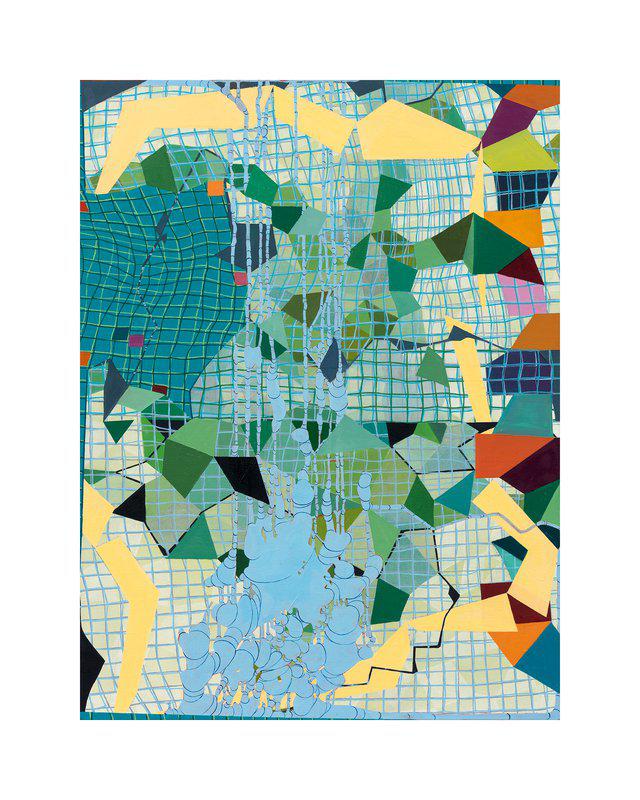

Captious Computation, 2020 - Lisa Corrine Davis

Lisa Corrine Davis’s paintings capture a point where order and regularity give way to the force and unpredictability of an external element, making them curiously apposite for the current time. The foundation of her paintings is layered grids and patterns but rather than formal rigidity, she shows them as warping as if under pressure. Map-like lines skew like loosely woven threads, indirect connections are drawn between random points on the surface. And over this framework come abstract blocks and blobs of colour. The tension between these two forces gives her work a real dynamism and power and sum up a state where chaos, contradiction and the energy that comes from opposing forces is natural. Davis currently lives and works in Brooklyn, with her work held in collections including MoMA New York, the J Paul Getty Museum LA and London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. This archival pigment print comes in an edition of 10, stamped and numbered with a certificate of authenticity.

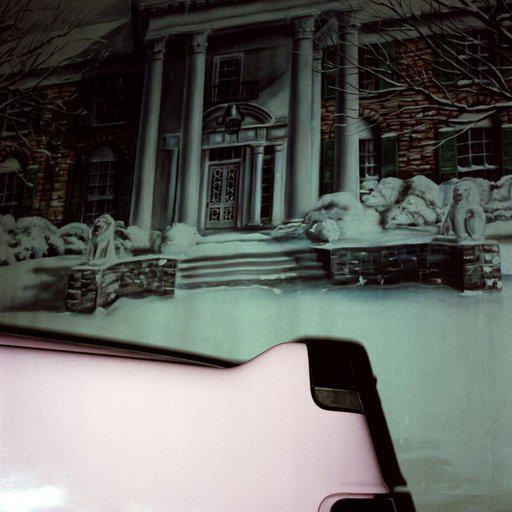

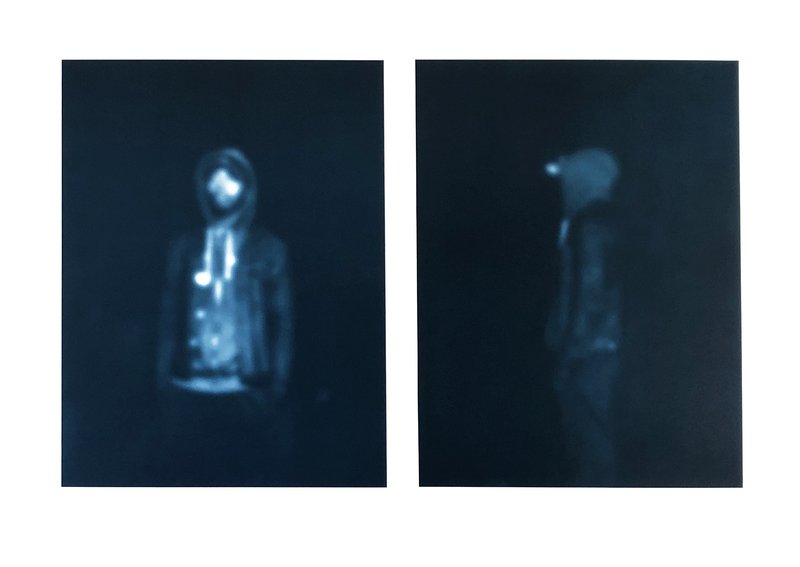

All The Boys, 2017 - Carrie Mae Weems

The images in Carrie Mae Weems’ series All The Boys and The Usual Suspects were made by the artist in response to high profile killings of young African-American men by authorities. At the opening night of their showing at LSU Museum of Art in Louisiana, she explained their importance: “The work that's in this room, the work that's dealing with this sustained level of violence, the sustained level of threat to the body, to the black body, to black men, to black women, to people of color, to women — the sustained history has been sustained for a long time. And so, the images that are on these walls are images that we all know one way or another," she said.

“We will all grapple with them one way or another. You've seen them on the news one way or another. And we've decided to look one way or another or we've decided not to look one way or another." Since her 1990 series Kitchen Table, Weems has looked at the portrayal of marginalised voices in American society and how the way we portray them visually shapes our response to them. Where that was once the black and white, cleanly-lit pictures of women at the table, now it’s surveillance images of young men, enlarged and magnified, leaving them with a ghostly, blurred quality. “It's painful to have to deal with this work constantly, but it's also painful to deal with this life constantly,” she said at LSU. “And the threat constantly. And the challenge constantly." This work is a lithograph, signed, numbered and dated by the artist in pencil and limited to an edition of 30.

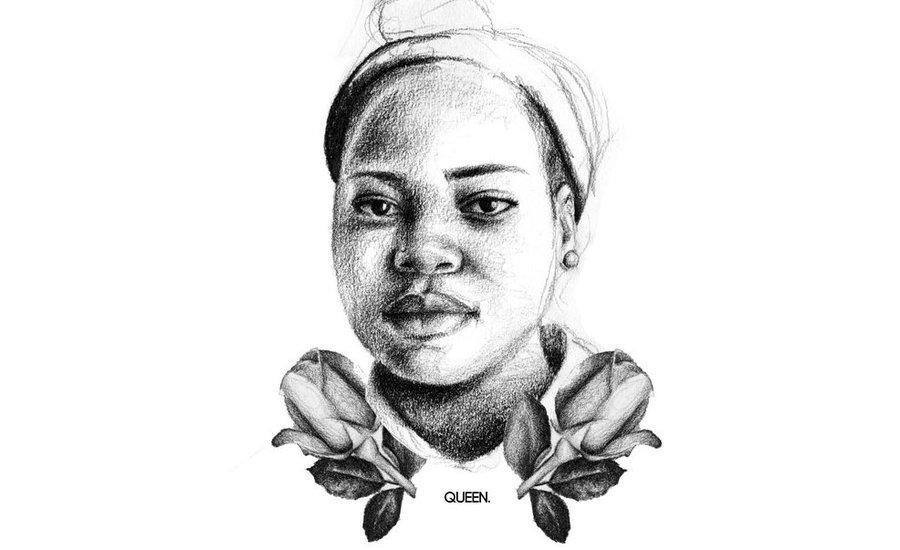

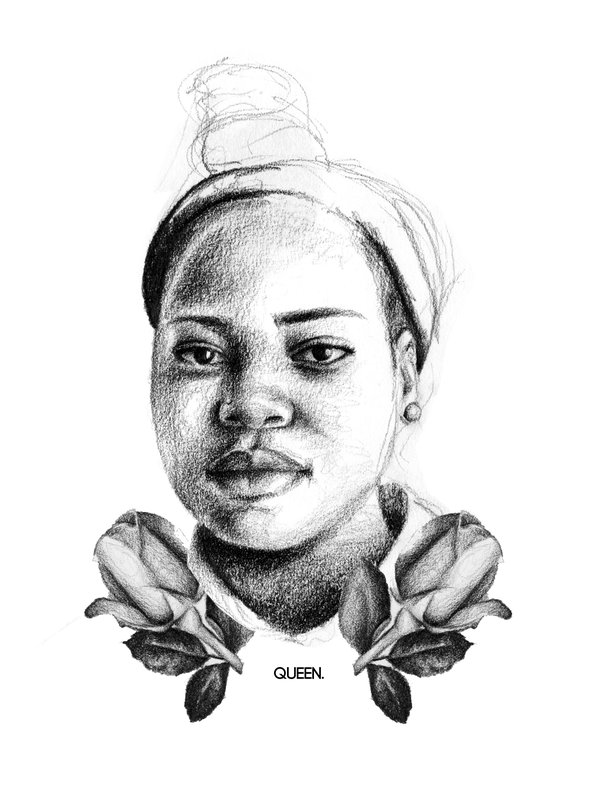

Black Girls (Queen), 2018 - Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

Over the last decade, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s painting has been exhibited in gallery shows from Manifest (LA) to Rutgers University (New Jersey) and Round 48 in Houston. However, her impact goes far beyond regular institutions and has rendered her as something between an artist, public intellectual and social activist. Named in 2015 as one of Forbes 30 Under 30 and profiled by the New York Times and NPR, she has lectured everywhere from the Brooklyn Museum to Stanford University; her work has been featured on BET and other TV networks; she was art consultant for the Netflix series She’s Gotta Have It. Her artistic and public work tackles the issue of violence in public spaces head on – most famously in her epic street art series, Stop Telling Women To Smile with its imposing, unflinching monochrome portraits of women looking down on streets from walls worldwide from Mexico City to Paris. “The word ‘Queen’ is typically reserved for some, but can actually be attributed to all,’ she says of this portrait. “It’s about recognising the power and beauty in all of us and celebrating the brilliance of being exactly as you are.”

Freedom or Slavery, 1998 - Elizabeth Catlett

While born into a middle class family in Washington, Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) was the granddaughter of slaves. Originally awarded a scholarship to study at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, the offer was revoked on the grounds of her race, with her eventually becoming the first woman to graduate as a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Iowa instead. Influenced by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo while travelling through Mexico, she began to portray African American women in the Southern states, working in linocuts as well as paintings and prints, drawing on Primitivism and Cubism to portray the lives and faces of ordinary people. “I have always wanted my art to service my people,” she once said. “To reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential.” After being investigated by the US House Un-American Activities Committee during the 1950s, she took Mexican citizenship in 1962. This relatively late work is a colour lithograph, signed, dated and numbered and from an edition of 100.