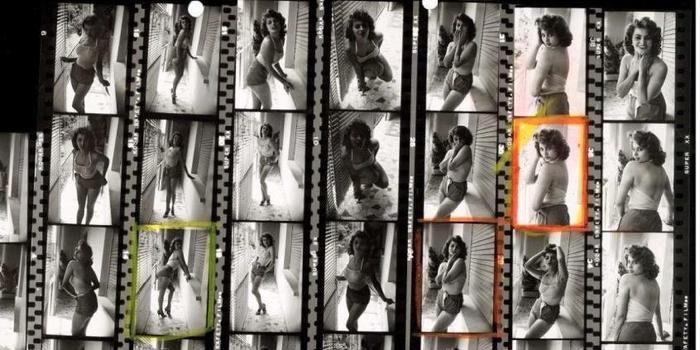

Being a photographer, these days, is nothing special. Millions of people routinely snap a dozen photos, edit the best ones, and publish them for their friends to see—all with a few clicks on their iPhone. This wasn't always the case, of course, as one can vividly tell from Kristen Lubben'sMagnum Contact Sheets, a tribute to the largely bygone age of physical film, darkroom chemistry, and, yes, contact sheets, the crowded prints that allowed photographers to chose which images to blow up and release into the world. To find out what these sheets—all, in the book, by photographers from the legendary Magnum agency—reveal about the processes of some of the greatest names in the medium, Artspace's Alex Allenchey spoke to Lubben about the outmoded filmic tool, and what we lose with its disappearance.

Starting with the basics, would you explain what a contact sheet is and how photographers and editors use it as a tool?

Contact sheets are not widely used anymore, owing to the advent of digital photography, but for most of the 20th century it was how photographers edited their work. They were the first printing of the negatives, really just a rough draft, that allowed photographers and editors to look at everything they had on film and then decide what images they want to enlarge and print.

In writing your book Magnum Contact Sheets, published by Thames & Hudson in 2011, what was it that first intrigued you about contact sheets, and how did you start the project?

In part it's the timing. Now that digital has almost completely overtaken traditional film photography, we're able to see this way of working—which for so many years was taken for granted as part of photography itself—as a historical process. So, in many ways contact sheets stand in for the whole revolutionary sea change that is taking place in photography. And there are many other things that make them interesting: they're unedited, they're sort of like an artist's sketchbook, and you get to see every image in a sequence. That's something you see a lot in the book—as you look through the contact sheet, you can see the photographer's working process and the conditions in which they were shooting. In many cases you can learn much more about their work through the full unedited sequence than by just looking at the final image.

Jumping off that point, your book sheds light on famous photographers' contact sheets, some of which were previously only available to archival researchers or industry professionals. Why did you feel it was so important to release these to the public? And how do photographers feel about it?

A lot of photographers are very private about their contact sheets and don't consider them something to be shared. People that I talked to described what a nerve-wracking process it is to make these images public because they can reveal too much about their working process, or take away the magic of the final moment. But at the same time, photographers are all invariably fascinated by each other's contact sheets. They're especially interesting for a photographer because you get that sense of standing in somebody else's shoes and looking through the camera with them as the work develops. I hope that the book can also serve as a reminder of the importance of archives and of preserving this sort of material. Especially as we move into the fully digital age, I don't think people have fully worked out how we are going to archive the material that's being shot today.

What does the inclusion of outtakes in contact sheets tell us about the work of great photographers? Since these outtakes are included, is there more of a backstory? Do all iconic photographs have good contact sheets?

I would have to say no. Sometimes they aren't as surprising as you would expect. I guess it depends on what you find interesting about contact sheets. For me, it's the ones where you find something you wouldn't have expected that went in to the making of the photograph. I think they all have different qualities and they all have different stories to tell. Some of the best ones in the book are great because of the narrative that goes along with it and the photographer's accompanying explanation. In other cases, it's just seeing how somebody works. A photographer may have taken just a single frame of a great shot, or in other instances you can see somebody really working through a scene to get the right shot. I don't think there's any one thing that you can see in a contact sheet that defines a great photographer. Each is interesting in its own way, they all tell a different story.

We have a handful of the photographers that you mention in the book on Artspace, including Elliott Erwitt and Burt Glinn. What did you glean about their processes and methods from their contact sheets? Are there any interesting anecdotes about these photographers?

Well, the Erwitts are some of my favorites. The more well-known one is The Bed, of his wife and newborn baby, which is beautiful because it's just a family snapshot that happened to turn out perfectly. In the contact sheet you see that it was just him and his wife and his family handing the camera around to take pictures of this new baby, and he managed to get one iconic picture that wound up being in “The Family of Man" [MoMA's landmark 1955 photography exhibition curated by Edward Steichen.] Then you have Nixon and Kruschev, which is an example of seizing the moment and being in the right place at the right time, and managing to get a shot that's both provocative and kind of funny. The third one is a complete opposite of the baby example, where he is out on a walk with his friend Hiroji Kubota and told Kubota to give him his camera because he saw this guy sitting on a stoop with his dog. Then he proceeds to take a whole roll of film of a guy with his dog, just lining it up perfectly. And in the contact sheet you can see him moving, inching back and forward, up and down, making minute adjustments until he gets exactly the shot he wants, and the whole roll is filled up with exactly the same picture, essentially.

What about the Burt Glinn photos?

The Burt Glinn sheet with Che Guevara is so completely cinematic, it's like watching a film happen. Guevara is so animated and unaware of the camera, and you just see him gesturing—it almost seems like you could speed it up and it would look like a film unfolding. That's one work where the sheet as a whole is incredible, and while there are individual frames that are particularly great that you can pick out of it, it's almost more satisfying to see it all together.

Do you see each contact sheet as a work of art in itself or more as a document of the total photographic process?

Some of them really are just incredible as objects, but I'd almost hesitate to get too precious about them and treat them as individual artworks. I think they really are inseparable from the working process and I like that kind of informality. Even though they do have incredible aesthetic interest, I like viewing them as they were intended to be, which is as real working documents.

Some photographers, like Richard Avedon, have incorporated elements of the contact sheet into their finished work and left the cropped border of the sheet visible around many of their classic portraits. When and how did this tactic arise and what is its influence on contemporary photography?

It came about as an aesthetic strategy in the 1960s, when artists like William Klein started to use it. There was an interest in film at the time, so contact sheets related to film in some ways. Other artists were interested in Minimalism and the grid. Then, at the same time, the rise of photography as a recognized artistic medium was just exploding, and contact sheets were something that really spoke to the process of the medium. The focus on process was really important in other artistic practices in that period, so revealing the process of photography was important to a lot of people. That's still going on today, and I think being used in a lot of interesting ways that reference analog photography and traditional photographic practices. I think that there's more interest in the contact sheet now, and in materials that look different than those in standard, commercially available photography. It resonates in a particular way. Some of the the most recent contact sheets in the book are actually examples of that, with Chien-Chi Chang, Jim Goldberg, and others playing with the form of the contact sheet.

Do you feel that contemporary photographers working with digital film are at a loss for not having to use contact sheets? Is their circumventing of the traditional editorial process necessarily a bad thing?

In many ways they're circumventing the traditional process, but in some ways that's an exciting thing. I don't want to sound like a luddite and say that things were better in the old days. You hear stories of photographers having to have their film shipped off, and they would have no role in the editing process, or things would be mislabeled or misused—there were a lot of compromises with the old system as well. The role of the photo editor has been greatly diminished and some people think that's a loss because that's a unique skill set, but there's also an advantage to the photographer being able to have a greater hand in the editing of their work. Obviously now there are so many more opportunities to show your work yourself and to circulate it in ways other than the mainstream media. There are just so many more outlets and more ways of storytelling, so ultimately I think it's a good thing.