On the face of it, documentary photography is the most straightforward end of image creation, the result of being in the thick of the action with even the most basic camera to hand and a quick enough response. It’s hard to think that Robert Capa’s The Falling Soldier would have been more impactful had he had a more expensive lens, or extra time to light and frame the shot.

But since its inception as an art form, the most gifted photographers have pushed the boundaries of what documentary is and what it can do. And over time, our perspective on these images changes: Jacob Riis’ straightforward 1890 studies of New York poverty, How The Other Half Lives now look eerily intimate as their wretched subjects stare straight down the lens at the contemporary viewer; August Sander’s simple portraits of all levels of German society in the early 1930s look to us now less like a straight record of a people and more a taxonomy of the horrors that were about to engulf the continent; Paul Fusco’s quick-fire crowd scenes shot from JFK’s funeral train now stand as a historic record of a country wracked by grief and social chaos.

Dorothea Lange , currently the subject of a vast and fantastic retrospective at MoMA, once said that the power of her images lay in them ‘(taking) an instant out of time, altering life by holding it still.’ But perhaps their real power develops in the years which follow, and in the way that the story of the photo changes along with our own perspective. Over the last decades, the best photographers have moved documentary into new subjects, new technology and new formats, but still with the same impulse: to capture that fraction of a second and give the viewer an image which lives on to tell a much bigger story. Here are some of the best examples currently on Artspace.

ROBIN GRAUBARD - Warhol + Sprouse (1987)

Robin Graubard’s work has taken her all over the world, from downtown Eighties New York to the warzones of the former Yugoslavia. The New Yorker described her pictures as ‘fresh, loose and charged with tenderness’. She photographed Brooklyn mobsters and Romanian street kids, but also Donald Trump and Richard Nixon . This shot of Warhol on the street captures him with his associate and fashion designer Steven Sprouse, one of the few people to have had as creatively varied an existence as the artist himself (Sprouse made costumes for Blondie, worked with Keith Haring and Marc Jacobs, and was the subject of Warhol’s neon-tinged 1984 screenprints series). This image captures a moment in New York’s history when the yuppie wave is rising, the city’s long journey towards a kind of respectability is beginning and the chaotic art riot of the first part of the decade is coming to an end. Warhol himself will be dead within months, and a part of New York life will be gone for good.

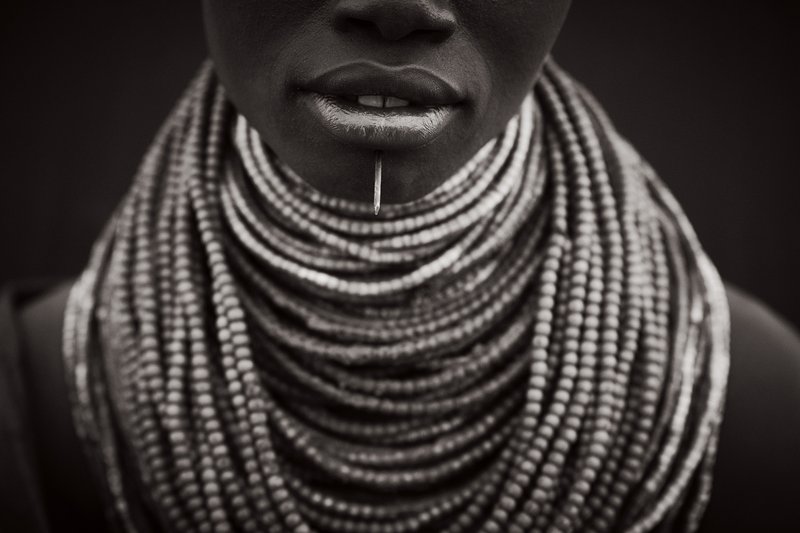

DREW DOGGETT - Nonguta in Profile (2017)

Drew Doggett’s work was described by one critic as having the qualities of ‘National Geographic meets Vogue.’ Having worked early in his career assisting the likes of Annie Leibovitz and Steven Klein, his photography has the precision and style of a fashion shoot – close-up detail, bold use of negative space and a playful use of scale. However, since a creative epiphany on a cycling holiday in rural Vietnam, Doggett’s eye has been drawn to a far wider range of subjects.

Travelling worldwide, he has photographed groups who are in some way disconnected from modern, globalized life – the Himalayan tribes of Nepal, the seminomadic people of Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, the unbroken wild horses who run down the beaches of Nova Scotia. With over 90 awards to his name (including a distinction from the Royal Photographic Society), Doggett’s work currently sits in collections including the Smithsonian African Art Museum (DC) and the Mariners’ Museum (VA).

This particular work is from 2017 and comes from his series Desert Song: Compositions of Kenya, an assignment that saw him document the women and children of the region. ‘Confident and regal, the women of the Samburu and Rendille cultures are classically and timelessly beautiful,’ says Doggett. ‘I find their strength and pride in their heritage to be an extraordinary part of their identity.’

DAVID MALIN - IC 2118, the Witch’s Head nebula, in Eridanus (2011)

David Malin stretches the boundaries and ideas of what it means to be an artist. First and foremost he is a scientist, but through his work he is also an astronomical photographer. After moving to Australia from Britain in the 1970s to work under the dark skies of New South Wales, he has discovered two completely new galaxies – Malin Carter and Malin 1 – and created a photographic record of the sublime wonders that he has seen. Malin concedes that working at this scale, many of the photographer’s usual techniques are obsolete, but this encourages more innovation: "In astronomical photography, you can't choose the lighting or rearrange the subject matter," he reminds us.

"Our expression with the images is about cropping and representation and tonality." Long exposures capture the trails that the stars leave behind as the earth rotates, and in this stunning image of The Witch’s Head nebula from 2011, a vast dust cloud around the super-giant star, Riegel, glows from 800 light years away.

"Since human beings evolved we have been looking at the sky. When the telescope was invented, vision was expanded to see more of the universe and it changed our perspective of our place in it. In 1000 years time someone will come along with new technology and they will look at the same universe in a completely different light.’" This image, of this one second in space, will never be recreated.

LARRY CLARK – Untitled Kids Skateboard (2013)

Throughout his long career – starting with the landmark documentary book Tulsa in 1973, Larry Clark has repeatedly, obsessively, turned his lens onto the edges of youth subcultures. What originally looked like voyeuristic snapshots of lives lived in the margins have gradually accrued into a major, lifelong study of a kind of secret history of American life.

Enormously influential on several generations of photographers who followed him, Clark’s documentary world view has also shaped everything from the publishing aesthetic of Vice, the streetwear culture around skateboarding and an entire generation of independent cinema thanks to his film Kids. Hence Clark’s collaboration with skate label Supreme feeling like such a natural fit – the screenprinted full-size board depicting Leo Fitzpatrick’s shoplifting scene from the film, with Clark’s signature on the reverse side.

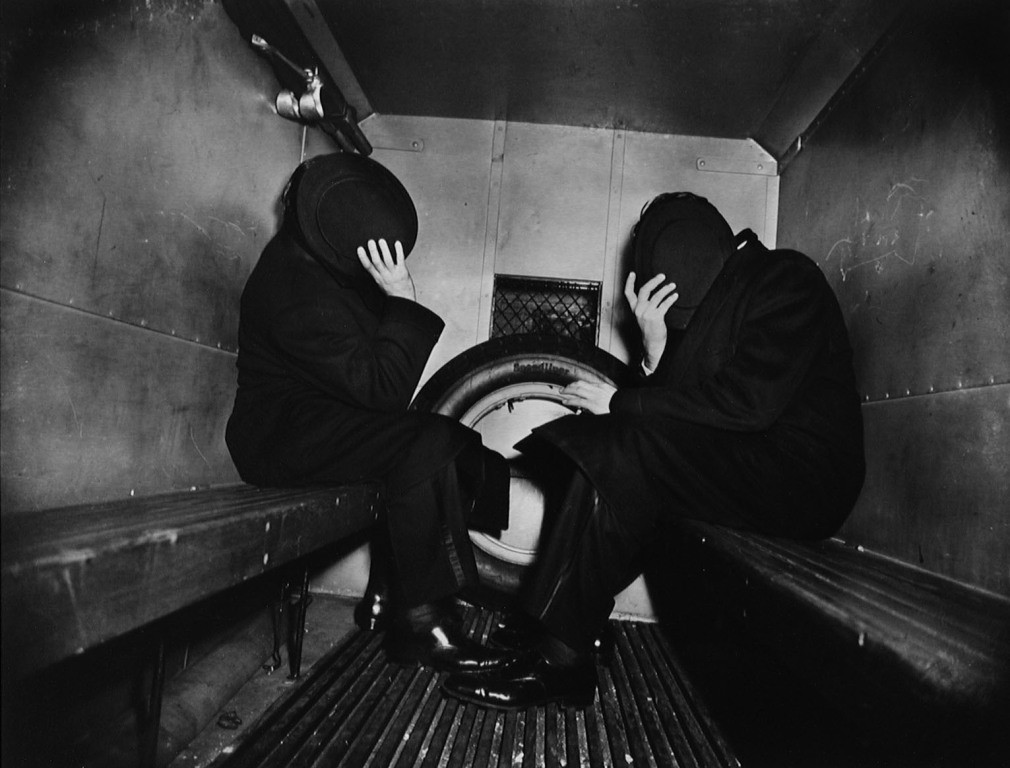

SEBASTIAN SALGADO - Coal Mining, Dhanbad, Bihar, India 1989 (1989)

On the face of it, the contrast between Sebastian Salgado’s work and that of Larry Clark is huge: Salgado has travelled through more than 120 countries, can devote five years or more to a single project, works in a spectral shade of black and white and imbues his images with a dignified stillness. But as photographers, there is a similar impulse – a complete immersion in other cultures, groups and ways of life, and an unvarnished documenting of that for the outside world to see and understand.

Originally an economist with the World Bank, Salgado moved from a statistical analysis of the international flow of goods and material to a material one, photographing oil production, cattle camps, gold mines, salt flats, commuter surges and rainforests. In this image, three of the coalminers in Bihar, whose work underpinned the industrial-economic growth which has transformed India over the last 30 years. Salgado’s work is a vast document of the grid that underpins human life on earth and each image is a tiny element of that.

RICHARD MISRACH - Golden Gate Folio (2000)

Richard Misrach is one of the most significant photographers of his generation, considered a major part of the 1970s renaissance of both color photography and large-scale presentation. He has repeatedly explored the empty spaces in America’s geography, conveying the overwhelming scale of the country’s landscape.

He has photographed cloudbanks and lakes, wide panoramas of shorelines studded with bathers, endless desert roads which dissolve into the horizon, and the graffiti which appeared through the abandoned quarters of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

This image is from his three-year project Golden Gate, which saw him capture the bridge at multiple times of day and night from a fixed point on the porch of his home. A Guggenheim fellow, Misrach has received the Kulturpreis for Lifetime Achievement in Photography from the German Society for Photography.

RELATED STORIES

These Sports Themed Works Will Make Your Collection A Winner