As the medium in which artworks of all varieties can often begin, drawing holds a unique position in art history. However, beyond their status as documents of a larger artistic process, drawings are also rich ends unto themselves, providing the viewer intimate access to the artist's brain, if you will—projected directly onto a piece of paper, without the layers of revision required by a painting or the considerations of materiality that buoy sculpture. These nebulous possibilities of the medium, which can simultanously convey the immediacy of cave painting and the sophistication of a blueprint, served as the curatorial inspriation for renowned curator

Francesco Bonami

's new show "Year After Year: Works on Paper from the UBS Art Collection," on view through June 21.

The initiating exhibition of a new ongoing collaboration between Swiss global financial corporation

UBS

and Milan's

Galleria d'Arte modern

(GAM), the exhibition is the latest group show for Bonami, who was able to draw upon UBS's substantial collection of contemporary art. (You may know the bank as an art patron from its longtime patronage of

Art Basel

.) Best known for his 2003

Venice Biennale

show "Universes Within Universes," Bonami is also a writer, the U.S. editor of

Flash Art

magazine, the artistic director of Turin's

Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo

, and a newly appointed jury member of this year's

Future Generations Art Prize

—in "Year After Year: Works on Paper from the UBS Art Collection," on view through June 21st, 2014.

We spoke with Bonami, who also happens to be a former artist himself, about working with the world-famous UBS collection, responding to the state of drawing in contemporary art, and his upcoming project in collaboration with architect Renzo Piano .

The works in this exhibition are all borrowed from the art collection of UBS, which is known for being one of the largest corporate collections of contemporary art in Europe, ranging from 1960 onward. Much of the work in the UBS collection is sculpture, photography, and video art. So why did you decide, for this show, to focus on works on paper?

The UBS collection is so vast—it includes 35,000 works—and this exhibition was, let’s say, just the beginning of an ongoing collaboration between UBS and the Galleria d’Arte Moderno in Milan. Five rooms of numerous scales were recently restored at the GAM, and I thought it would be an interesting gesture to start slowly, but with quality. Works on paper seemed to be the perfect medium for opening up the conversation and collaboration between UBS and the GAM.

There are 34 artists included in the exhibition. Is it fair to say that for many of them, drawing is not their primary medium? I’m thinking of artists like

Roy Lichtenstein

,

Rosemarie Trockel

, or

David Salle

, who are all known mostly for work in sculpture or painting.

Well, I would say so—maybe

Troy Brauntuch

and

Robert Longo

, for example, are known for their drawings. In the show we have a chalk drawing by black paper by Brauntuch, and one of the drawings from Longo’s iconic

Men in the Cities

series. So I think a few of the artist in the show are more associated specifically with works on paper, but for the others the works in the show are more like studies, and represent different phases of their process. So we considered many different types of work.

In the catalogue, you draw a comparison between an artwork’s affect and psychoanalysis, where you call drawing the artist’s “id” and painting the artist’s “ego.” There’s also a comparison you make that drawing is like poetry, while painting is like prose. So you’re saying that drawing is not just an unfinished or earlier stage in the conception of an artwork, but is actually, in a way, more deeply rooted to an artist’s creative mind. Could you elaborate on that idea?

I think that in looking at works on paper, the works we see are often studies, where the medium leads to other types of work, like painting or sculpture. But sometimes these works are fully developed. Particularly of the works in the show, many are autonomous pieces that are not simply unfinished sketches—they’re solid examples of the paper medium. The idea of ‘works on paper’ is open-ended, but it also has its own specific set of instructions and potential meanings.

The exhibition is broken up into sections—“Words,” “Gestures,” “Figures,” and “Portraits.” Within each of these sections, of course, there’s a lot of variation in technique and presentation. How broadly do you think the term "works on paper" can be defined? Or, what are its limitations?

There’s actually not too much diversion in the show. You could say, as an example, that a photograph, for instance, is a work on paper. But that’s a different thing. I use the term “works on paper” to refer, mostly, to drawing, itself. Although in our show we do have a self portrait by

Lucien Freud

, which is a watercolor on top of an etching the artist made; that’s the only work in the show where there is actually another medium present.

Do you think your own training as an artist informs your understanding of drawing?

Oh yeah, definitely. I wasn’t a good painter, I was a bad painter—which, ironically, means I have the advantage of being able to see both what is a bad painting or drawing and what is a good painting or drawing. I think that’s true. I have a little bit of an advantage, being able to put myself in the shoes of an artist and kind of understand where he or she wants to go, creatively, and where he or she wants to stop.

How do you envision the condition of works on paper in contemporary art, specifically? Especially as paper in everyday life is increasingly abandoned in favor of digital technologies.

The digital shift is definitely a concern in terms of the way it effects communication, information, documentation, and so on. In terms of art production, I think it’s another matter. Sculpture is a different subject, because, in a way, it's being affected more by technology than other mediums—there are new, more sophisticated ways to fabricate a sculpture than there were before, that allow artists to express themselves in different ways. But in terms of painting on canvas, or works on paper, I think those are media that are here to stay for good, into the future, and I don’t believe they’ll be substituted wholly by digital technology, or anything like that.

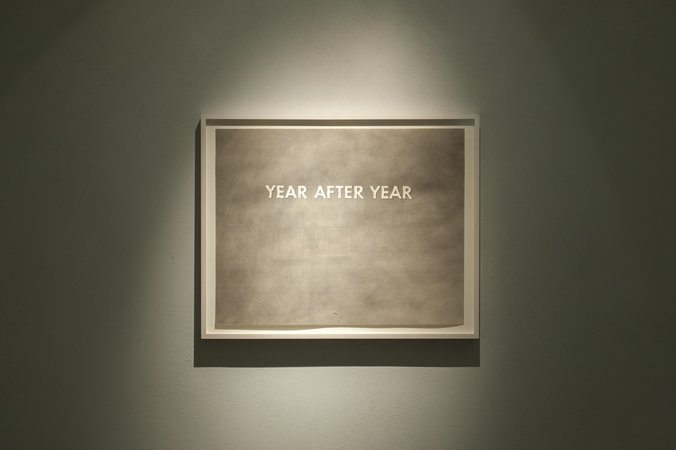

The title of the exhibition, “Year After Year,” comes form a work by

Ed Ruscha

. It refers to drawing’s continual presence through that time, and its ongoing presence in the process of creating a work of art.

Could you tell us more about the recent GAM renovation?

The fact that the GAM building was built circa-1900 and is this kind of “exhibition hall” gallery space, that defined our idea to create an exhibition that would be on a human scale. We wanted to reflect on the fact that there was a time when artists were producing work in their studios, and not necessarily thinking about the space where the work was going to be exhibited. I think the GAM museum works very well in this regard—the scale is good, and I think it has a reassuring effect for artists.

Today the contemporary art museum is not an “exhibition hall,” in this sense. Artists have the tendency to want to transform the space, or demand that things are changed, architecturally. In this case, the space is just what it is. We’re not necessarily going back to a past tradition, but I think we are going back to a more balanced relationship between the space of the exhibition and the space where the art was produced.

Italy is a major center for contemporary art, with, most obviously, the Venice Biennale, but also the World Expo happening in Milan in 2015, and a number of important venues like the Pinault Foundation, the Prada Foundation, and the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, where you’re the artistic director. Does this exhibition or the UBS collaboration with the GAM respond specifically to artistic or cultural conditions in Italy in general, or in Milan specifically?

Well, it’s a pretty small show—to say it responds to conditions in Italy might be unfair. But, with this exhibition, especially in comparison to some of those other institutions, we suggest that focused, small projects can have a weight and an impact that does not necessarily have to come from a huge production and a huge investment of money—you can do something with very balanced means, and make it something that people can enjoy.

There’s also Drawing Now Paris, the all-drawing art fair that opened recently. The last one was a big success—perhaps indicative of a recent uptick in interest in contemporary drawing?

I didn’t know about it—I would like to see it. I know there are collectors, big collectors, whose collections focus only on works on paper.

What are you working on next?

I’m helping the Italian architect Renzo Piano. He’s developing and building a new headquarters for a Chinese company, JBNY, in Hangzhou. They’re building a new headquarters, but they also want to build a project room and artist-in-residence building to show work by young artists, so I’m helping to develop the program—not curating, but helping to develop the overall vision for the project, which should open in 2016. It will host exhibitions and performances—things like that.