When the Whitney Museum of American Art opens the doors to its new home in the Meatpacking District this week, it stands to be the most seismic development in the New York art world in a generation, abruptly bestowing downtown Manhattan with a world-class collection and a slate of cutting-edge programming guaranteed to make the foot of the High Line the hottest new contemporary-art hub.

A $422 million building designed by Renzo Piano that combines the monumentality of a fortress with the open conviviality of a pleasure cruise ship, the museum will just about double the museum’s interior exhibition space to 50,000 square feet, with 18,000 of that given over to the city’s largest column-free gallery; in addition, there will be 13,000 square feet of outdoor exhibition space on a network of terraces, a 170-seat theater, a black box performance space, and mundane but critical amenities like a loading dock inside the building and a conservation lab, neither of which the Whitney had before.

Walking through the collection as it has been rehung in the new building, one is taken aback by how truly the museum had been straitjacketed in its former Marcel Breuer -designed lodgings on Madison Avenue (now under the stewardship of the Metropolitan Museum of Art )—it feels as if the Whitney has finally been able to burst free, stretch out, and reveal its rangy true self. The inaugural exhibition, a deep dive into the collection’s previously hidden holdings called “America Is Hard to See,” inspires the feeling that a new era in American art is stirring to life, with a richer history and new names that might make more than a few textbooks out of date.

So, where does the Whitney go from here? To find out Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Donna De Salvo , the museum’s chief curator, about what the Whitney hopes to accomplish with the new building, why American art now encompasses many nationalities, and how the institution plans to navigate the twin explosions of the digital era and the art market.

RELATED LINKS:

The Whitney's Buried Treasures: 10 Rarely Seen Masterworks Making Their Debut in the New Building

The new Renzo Piano-designed Whitney Building

The new Renzo Piano-designed Whitney Building

The move into the new building is a seminal moment in the museum's history, and you have been embracing the shift as an occasion to refresh, rejuvenate, and reimagine the institution from top to bottom, from revising its graphic identity to rehanging the collection to creating opportunities for artists to explore new modes of working. You have also reached back into the museum’s history, and a new handbook to the collection reveals a wealth of art that had been previously buried in the Whitney’s holdings. In driving this overhaul, what were some of the key concepts that were at the heart of all these decisions?

What’s driven a lot of it is how to make concrete the core mission of the Whitney in terms of its commitment to living artists. The way we approach history is with a spirit of openness that comes through the lens of the contemporary, and I think the methodology that we have followed is one that acknowledges and respects history and the specificity of certain historical moments, but without being limited by prior reads. There is a willingness to put forward new narratives, new stories, to be provocative, and to see history as something that is porous and open. I think that maps very closely to the way artists often work.

It’s not a new thing, and if you go look back at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century and Duchamp and even Warhol ’s “Raid the Icebox” show at RISD, there is a real history of the way artists themselves have looked at history, and it tends to be characterized by a real sense of something being ever-present, and a sense of this openness. I think that’s very core of what we have tried to do, and maybe it goes back to the days of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and the fact that we were founded by an artist. The spirit of really tracking close to the process of art-making itself and the thinking of artists is something that has permeated the way the Whitney has operated for many years, and that has manifested in the way we’ve designed the building.

So, each of the iterations that you mentioned express this mission. In the handbook, you will see a larger number of artists not seen before—many more women, more artists of color, and generally real recalibration of the way we look at art in the United States and its history. I hope this comes through even in our graphic identity, which arose from the notion of a responsive W and the idea of trying to be responsive, not reactive, to what artists are doing, with that willingness to be open-minded and to think anew.

The Whitney Studio Club

The Whitney Studio Club

As you mentioned, one of the remarkable things about the museum is that it was founded in the bohemian precincts of New York’s downtown by an artist—albeit an especially monied artist, born into the Vanderbilt railroad-tycoon family and married into the wealthy Whitneys—during a period where American art was seen as a poor, unlettered cousin to European art. The museum’s earliest incarnation, the Whitney Studio Club, was in fact less an exhibition space than a social space for penurious New York artists to congregate, socialize, and grab some sustenance before heading back to their garrets. Has this kind of mixed-use concept of the museum as a social space for creatives figured into the design of the new building?

It’s really part of the ethos of how we think. At that point, in the Studio Club, the social space was about building and finding a place for that community to form, because otherwise there wasn’t any support for it because of the condition of American art and culture. But today, I think it’s always fascinating to see that many of the artists who have shown at the Biennial, for instance, or have been in various exhibitions at the Whitney, have a fondness for the museum and feel they’re a part of the community. As much as the Whitney is a museum of American art for this country and for the world, it also has a very strong New York presence, and I think that has been really key to artists feeling a sense of connection to this museum over many years. You can see it at some of our openings—every artist in the permanent collection has a membership to the museum, and they come. They have a sense of ownership, if you will—a sense of belonging at the museum whether their work is on view or not.

When we were in the process of thinking about this museum, we actually had some roundtable discussions with artists, we listened to artists, and artists have since come to this building in many different phases of its construction. Some of the architectural considerations are about the physical bringing of people together, we also want to make sure we’re representing the voices of the artists, whether it means making sure the building doesn’t have any floor grates, because we know artists don’t like that, or calibrating the heights of the ceilings and creating spaces that we feel art will look best in. People don’t often think about those things, but they were very conscious decisions on our part in terms of the design of this building. As the chief curator here, representing my curatorial colleagues, I know we’re all advocates for the artists, and we’re deeply concerned with creating spaces that are going to be great for looking at art.

That’s refreshing when so many museum designs and expansions seem to be primarily concerned with bringing in maximum crowds, or creating grabby exteriors while shortchanging the actual art contexts within.

Well, yes, it’s a balance for any institution, and I’m sympathetic. It’s a fantastic thing to have a greater number of people wanting to come see art. But there’s this fine line there, and I would say the key is being conscious of it and keeping the art high on your agenda. We debate a lot of things here at the Whitney, and we spent a long time talking about the reveal between the wall and the floor, discussing the difference between 3/8 of an inch and half an inch. You can imagine an artist getting in the same kind of conversation, because that level of detail really makes a difference.

Keeping that high on the agenda is where Adam’s leadership is very key, because when you run an institution, you’ve got to pay the light bills. There are a lot of very pragmatic nuts-and-bolts decisions involved, but throughout it’s important that we never forget why we’re here. If you lose sight of that, that’s when you start to get into trouble. But even if you are in trouble, you can still go back to that and ask, “Ok, what are we about?” It’s a kind of thing that we talk about a lot, because while you would think it’s automatic, it’s not.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and Juliana Force

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and Juliana Force

Today contemporary art is very much at the forefront of the museum’s programming, but the collection is terrifically rich with older art that of course was contemporary at the time it was acquired, including pieces from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s day that show what much of American art looked like before the advent of Modernist influence. For instance, there’s a photograph of Whitney and her advisor Juliette Force talking amid a clutch of statues that look remarkably neoclassical—a body of work I’ve never encountered in the museum. Where does this older art, particularly statuary, fit in the museum’s collection?

The museum at one point had 19th-century art in the collection, but a decision was taken around the late ‘70s to create a dividing line of around 1900 and deaccession the works pre-dating that. There are echoes of this past however, and it was interesting when we included the George Bellows painting of ice floes in the Hudson River on the top floor, because that piece harkens a little bit to aspects of late 19th-century art and the age of American Impressionism, with artists like Childe Hassam and William Merritt Chase. They represent some aspects of influence by European Impressionism, but then the Modern forms of Marsden Hartley form a distinct break, and that break away—of American Modernism asserting itself—was largely what Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and Juliana Force were attracted to.

I remember that there was that amazing view of the Hudson, where you see a painting of the Hudson and then you have the river flowing outside. It calls to mind this early era of American art that’s not, to my mind, represented in the Whitney’s collection, which is the Hudson River Valley School. With this growing curatorial tendency to look both forwards and backwards simultaneously at the art history, is there any idea that the Whitney might ever start looking back at this American art?

I don’t envision a time when the Whitney would be collecting in that area. As I said, at one point there were works of that period in the collection, and it’s interesting to look at some of the Hudson River landscape artists like Jasper Francis Cropsey and Thomas Cole represented in the New-York Historical Society or the Met or the Brooklyn Museum . In other words, there are museums in the city of New York where you’ll find that kind of material. But I imagine there’s always the possibility for us to look back at this period through the exhibitions.

You know, Dan Flavin had an extraordinary collection of Hudson River landscape drawings that Dia actually supported the purchase of, and you can see where Flavin might have been interested in that kind of reading of the sublime. I think there are ways of going to those places that might make sense in very particular instances, but the Whitney is really about going forward, and I think the museum is really committed to the narrative that takes the beginning of Modernism in America as its starting point.

Interestingly, once the Whitney finally opened as a museum, it briefly had a policy of not showing work by living artists so as not to wade into the messy territory of influencing the market. Obviously, that policy went by the wayside almost immediately, with the birth of the Whitney Annual. How does the museum now view itself in relation to the market?

With the way things are now, time has collapsed. You can have interest in an artist who has no market and then by the time you’re ready to show the person, thinking you’re ahead of the curve, they’ve already burst on the scene and are having gallery shows. It’s a complicated issue in terms of how fast things move. The flipside of the problematics of the market for a museum, as people often forget, is that we buy art to keep—though in certain instances we might deaccession a work, usually to get another example or a more relevant example for the collection. But the market has become difficult because it makes it harder for us to acquire work, frankly.

So we try to be as far ahead of the curve as we can, because that allows us to purchase works, hopefully, that we can afford to buy. And I think the fact that we have a track record of showing artists before they’ve been confirmed by the market is something that is very key for us. There’s a certain reality that it’s a bigger market, there are lot more galleries, a lot more artists, and everything has accelerated. That acceleration may mean that you are a little bit behind the curve as opposed to ahead of the curve. Do we show things because we think they have market value? That’s never what drives the decision. It just wouldn’t be interesting, frankly.

This is really where the construction of the program comes into play. We strive to create a program that has a balance, and oftentimes that may mean in one show you have a better-known figure and then later an artist who is perhaps not going to be the most popular in terms of audience. You know, we’ve committed exhibitions to like artists like Paul Thek , we have a forthcoming exhibition in the fall of 2016 of David Wojnarowicz, a very vanguard artist of the ‘70s and ‘80s who is not a household name but was very influential for a whole generation of artists who were engaged with looking at the AIDS epidemic, and a different notion of New York itself. Then, on the other hand, you can also have a Jeff Koons show, which had enormous popularity for all kinds of reasons, and we did a very scholarly, rigorous exhibition. The market is fickle.

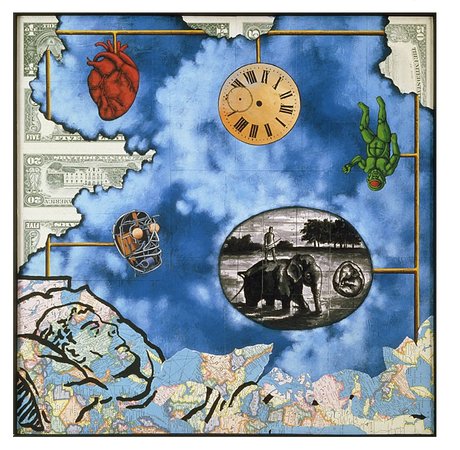

David Wojnarowicz's

Something From Sleep II

(1987)

David Wojnarowicz's

Something From Sleep II

(1987)

Museums are less fickle.

Yes, I think so. At least we try to be. We’re looking for things that have a meaning or an artist or topic that feels relevant but hasn’t been explored. What is it that makes something feel like it’s hitting a moment, or that there’s a need for it? That’s the kind of thing that you look for as a curator. It’s exciting—sometimes you get lucky and you just hit something at the right moment and it takes people 10 years to look back and say, “Wow, that was really interesting. That was so ahead of the game.” No one may have gotten it at the time.

One thing that’s so exciting about the new building is that it opens up new vistas in terms of display. Adam Weinberg has called the new spaces "inspirational" for artists. What new opportunities do they afford artists, other than expanded space?

We hope the building is both inspirational and aspirational, because when we were working with Renzo we really tried to think about how it would be used. The fifth floor is 18,000 square feet, and we designed it to be column-free, so that you can imagine the possibilities you have there. An artist could have a single work that might occupy that entire space, or a choreographer might have a performance that can move through that space in an uninterrupted way. Also, if a curator feels that they only need 12,000 square feet of space to do their project, that possibility is also there. We aimed for flexibility without anonymity. A criticism of buildings that aim to have the most flexible space is that you can wind up with something that feels anonymous or corporate, but I think Renzo really got it right here by bringing a certain kind of warmth and a human feel to the building along with the kind to flexibility we’re looking for.

What would you say are some of the biggest breakthroughs of the new building in terms of museological design?

Our outdoor terraces. What’s interesting about the roof is that it’s not a sculpture garden or terrace in a conventional way. I always see it as an urban stage. When you go out on that space you are in the city, in a gritty New York setting, with the river on one side and the city on the other. We have this incredible project when we open the building where Mary Heilmann will be using that space, actually hanging a work on the side of the building and using the building as a kind of canvas. She’ll also have these outdoor chairs there.

We thought, “Wow, this is perfect!” It’s a space that viewers will activate, and it’s a really generous kind of space because people can just hang out there, energized by the bright color and the sense of geometry. I can’t think of another space like that in New York, and we really wanted spaces that are distinctive and that people would recognize as unique to the Whitney. We’re inspired by it, and we hope that artists will be inspired by it too.

There are also the terraces that come off the galleries on the other floors, with an outdoor staircase connecting them all. Our theatre is pretty unique too, in a lot of ways, as a space that looks out at the Hudson. All of these are places that become activated by art. Currently we have a Felix Gonzalez-Torres piece hanging in the grand staircase. In this case, it’s a work that’s in the collection; in Mary’s case we’re dealing with a living artist. I think artists will show us how to use the space. We designed it, and they’ll just keep showing up.

Zoe Leonard's

945 Madison Avenue

(2014)

Zoe Leonard's

945 Madison Avenue

(2014)

The roof sounds like an inverse of Zoe Leonard ’s camera-obscura piece in the last Biennial, but instead of bringing the city into the museum you’re bringing the museum out into the city.

That’s very true. We’re actually bringing the museum into the city. I like the idea of a living room where the city is the walls.

One of the more interesting developments of recent years is that artists have been branching beyond simply making work in their studios, adopting the role of dealer, critic, publisher, curator, art fair-founder, nonprofit-founder, and even bar proprietor. Your last three biennials have in fact prominently involved artists as curators, from Michelle Grabner to Robert Gober to the indispensably eccentric Werner Herzog. How does the museum plan to bring these kinds of new operations in as well?

It’s a great thing, and we welcome it. It’s something we encourage through the Whitney’s Independent Study Program , which a studio program but also a critical studies program. I think it’s part of the trajectory of artists, and if you go back and look at the Bauhaus moment or Warhol’s Factory you kind of see it there too. I think artists avail themselves of all the opportunities available, and if one doesn’t exist, they invent it. Right now, for instance, Paul Chan is very involved with publishing . There are a lot of interesting artist-run galleries, like 47 Canal , where you have artists seeing themselves in an alternative vein and understanding the marketplace. In a sense, they have a sense of agency and control—they don’t just leave it in the hands of others. When you confront the market forces, to be empowered in that way is really important. I can see why artists do it.

For us, we work with so many artists in so many different capacities that it’s natural for us. Artists curating exhibitions is not a new thing—before curators came into existence you had artists who curated shows. Now the curator as a profession has become more acceptable, but it’s a relatively new thing. Artists have always been engaged in one way or another with curating or publishing, and now new technology makes it even more possible.

How does the new building impact the Whitney ISP, which is sited in Tribeca next to Santos Party House?

The ISP is still very separate, and we took the decision that they would remain in the space that they’re in. Ron Clarke has been leading them for many years, doing an extraordinary job, and they really are independent. We agreed that if the ISP should come into the new building that would change it—that’s there’s important about them remaining independent even in the sense of the built architecture. There would have been the danger of the program becoming institutionalized. I think it was the right decision.

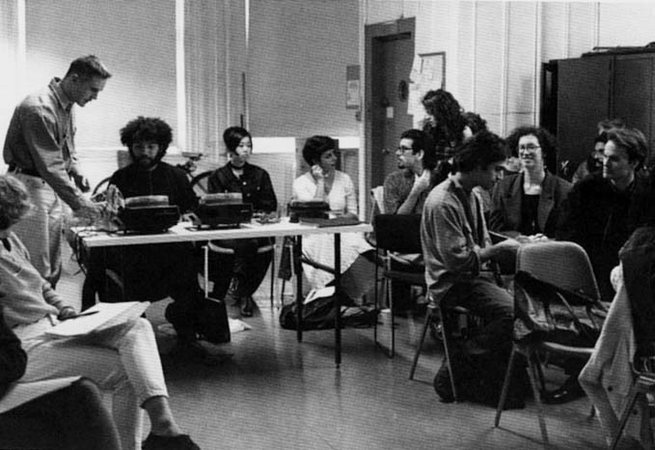

The Whitney Independent Study Program

The Whitney Independent Study Program

For much of the aughts, a critical challenge facing museums was to accommodate the rising tide of performance art , creating spaces and developing programing to showcase this work. This new building, as a result, is outfitted with plenty of innovate spaces for performance. How do you see performance fitting into the life of the museum amid the more static exhibition offerings?

It’s very interesting, this issue of what constitutes static. First of all, I’ll say that the Whitney has a long standing history with performance that goes back to the early ‘70s, with performances that took place mostly in the lower lobby, although there were some that took place on the second floor. Then, when the Whitney had its space on 42nd street, which was first in the Phillip Morris building and then became known as Altria, that became the space where much of the performance took place. If you go to our website you can see the remarkable list of people who performed there—it’s an incredible range of people.

It’s often about the intersection between performance and the visual arts, and we’re not Lincoln Center but we are a place that always looks at this intersection between visual and the performative. [Performance curator] Jay Sanders is part of the inaugural programing and he has looked at where performance and the collection come into collusion, if you will. He’s been looking at the history of performance and how it’s impacted the development of the visual art, thinking about Donald Judd and Robert Rauschenberg and that whole generation. But even looking at the performative that plays out in terms of ‘70s art-making, video, and other time-based media, it’s very interesting to think through what really constitutes performance.

Right now this is something that is very much on people’s minds. What do we mean by performance—what is the performative or the interactive or the participatory? This is probably one of the biggest and most interesting areas going forward, and a lot of museums are embracing it, like Tate Modern, where they launched the Tanks, and MoMA, which is certainly talking about performance spaces in their expansion. It will be really woven into our new building as a robust part. I wouldn’t want to say it will be normalized, but we’re committed to finding the right opportunities to make it a piece of our overall exhibition program.

Nowadays, the challenge facing museums is what to do with the rise of art that is so essentially tethered to the Internet. With artists making increasingly digitally involved (or “networked”) work, shows like the Triennial have to be increasingly allusive to bodies of work that largely lie outside the museum context, functioning almost like hyperlinked web pages—except that it’s impossible to click on a museum. How does the Whitney plan to accommodate these kinds of works?

It’s an interesting issue. Since 2002 we’ve had a program called Artport that is overseen by our adjunct curator of new media, Christiane Paul, who also teaches at the New School. It’s a series of commissioned projects that have changed over time, and they’re all archived and accessible online. We consider it, in essence, a kind of online exhibition, and if you go to our website it’s listed under our exhibitions. That’s our portal to Internet art , and we’re very committed to maintaining the authenticity of the site—in other words, that you experience the art through the terminal, through the computer screen. It’s not a necessity to put the screen in the gallery, and having the art exist on the Artport decentralizes the experience by decoupling it from the museum and liberating it, in a sense. That is the thing I find really fascinating about it.

For instance, we have a work in the collection by Douglas Davis called The World’s First Collaborative Sentence that was done in 1994, and it’s a never-ending sentence that you can access online and contribute to. What’s interesting about it is how it kind of anticipated the blog culture, in that it functions as a delivery system—it’s an expression of how digital space has reorganized the way we think.

In this kind of artistic universe, what is the role of the physical museum, and what are the limitations of the physical museum space? There seems to be a kind of anxiety on the part of some curators about the state of the museum, with Jeffrey Deitch even recently telling Massimiliano Gioni that he thinks the future of the museum is to become a Coachella-like mass in-person experience.

I can understand Jeffrey saying that, since he’s certainly interested in street art and hip-hop culture and that kind of immersive experience. The biggest challenge when you have a collection that spans 160 years, as the Whitney does, and you have artists that continue to make paintings and works on paper is that you have to find a way of accommodating all of that. If you become one thing, you exclude something else. I do think it’s possible to program things that are more festival-based, like Coachella. The most pressing issue to me is calibrating the level of interpretation you can provide through online components and supportive digital material to give people background information on particular works of art. We’ve gone through audio guides, we have hand-held devices, and today everyone has their phones.

Coachella

Coachella

It’s fascinating because these things change the notion of the kinds of experiences you want to offer people. At the same time, maybe it sounds old-fashioned to want a space that allows for contemplation, but there’s something to be said about a space like that. There aren’t that many opportunities in everyday life for that. And it’s an interesting issue why people come to museums. They don’t come for any single reason. We’ve done studies, it’s across the board reasons why come.

One of the reason many people come is for the Whitney Biennial , which has now seen its next iteration pushed back a year in order to rethink it to suit the new building. What are some ways you can imagine the show changing?

Well, the Biennial has always encompassed the entire Breuer building, with the exception of the fifth floor. We now have so many more spaces to activate for artists here that I think it’s going to be really exciting. These are spaces that are better—not just bigger but more expansive in certain ways. I think this will be a great opportunity for the artists and the curators who take over the Biennial because it will be a whole new instrument to play. Also, where the building is situated and the history of this area will give artists the chance to do things that are very site-specific, with the Hudson River outside and the piers, which have an incredible history within the history of art. You can also go back to the early part of the 20th century and think about the cruise ships that came through here, the longshoreman who were here, and the remnants of the sailors’ hotel that was along the West Side Highway. It’s going to be a whole new experience, and a place for new ways of thinking about making art. I think the next biennial will be very ambitious.

A defining attribute of the Whitney Museum of American Art is, of course, that it is a museum devoted exclusively to American art—an identity that has shifted tremendously over the years, and which is now the subject of the opening exhibition, “America Is Hard to See.” What does it mean to be a museum of American art today?

There are two distinct things here. One is that our collection is about art in the United States. We collect artists who don’t have to be born here, but who have contributed in one way or another to American culture. My colleague Dana Miller did this amazing survey, and the percentage of artists in this collection who were actually born elsewhere is incredible. Then we have our exhibition program, which is largely looking at American art but in a broader international context.

For instance, we did the Kusama show a few years ago, and she’s an artist who lived here in the ‘60s and was very involved with Judd and a number of other figures but then went back to Japan, and has since always maintained some kind of dialogue with the U.S. I think that there are ways that our collection tries to look at the particular nature of the U.S. as a culture of cultures, and then through our exhibition program we can at times look at artists that we don’t collect just because they expand our understanding. It’s interesting to think about how ideas are created, how ideas move and groove.

You go back to the early part of the 20th century and you had American artists going to Europe, or artists coming from Europe to live here. Now we have artists living all over the place. So we don’t just look at United States because it’s not possible to be involved with living artists and confine yourself in that way—the artists we’re looking at and the entire construction of culture in the United States is influenced by the world itself. I think there’s an advantage to our focus and, as I say, there’s nothing that prevents us from showing any non-American artist.

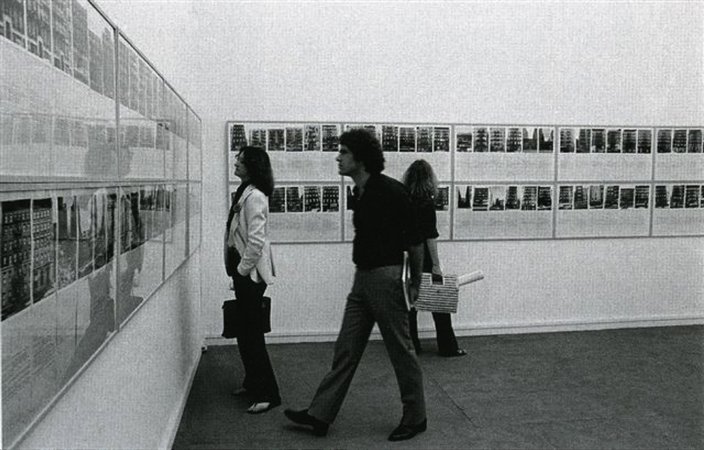

We’ve been deliberately moving in this direction with the things that we’ve added into the collection recently. A few years ago we purchased a work by Hans Haacke [ Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 (1971)], a major piece of conceptual art that really looked at the network of real estate transactions. The whole piece is comprised of public documents, and it’s from a period in the early ‘70s where artists were really looking at the system itself and the means of organization and tapping into that.

Hans Haacke's

Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971

(1971)

Hans Haacke's

Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971

(1971)

Haacke has lived in the U.S. since the ‘60s and is a part of this culture, and yet previously he was not in the Whitney’s collection. We just purchased our first work by On Kawara as well, and he was born in Japan and came to live here. It’s really interesting in terms of what we haven’t done yet but are starting to do more of now. I think the collection will begin to feel even more representative of the international, hybrid nature of American culture.

This point of view, intriguingly, is very much in tune with the way America acts on the international stage, as a propagator of a kind of global American ethos—something that many Americans would never think twice about, but which raises eyebrows abroad. Here at home, though, along with apple pie, mom, and Old Glory, one of the most essentially American artifacts is our boisterous, creaky, and altogether infuriating political system. How does the Whitney positions itself vis-a-vis the political landscape?

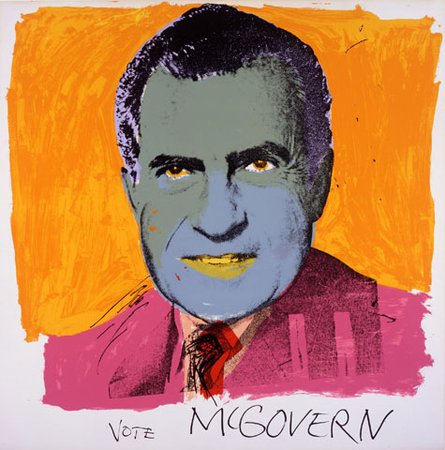

Well, we look at how how artists are being responsive to political and social situations. We have a gallery in “America Is Hard to See” with prints made in the ‘30s that portrayed lynchings in the South and were made in response to anti-lynching legislation that was before congress at the time. There are other prints in that gallery that look at the period of the Depression and the arrival of the labor movement. These were artists who were giving visual form to certain political ideas. That carries over to the political ‘60s gallery where we have the “Vote McGovern” poster by Andy Warhol, which pictures Richard Nixon. Here you have an artist who actually made a poster for the McGovern campaign, who created a text and image of a kind of commentary. You can read it various ways, but it’s a very powerful image in the way that Nixon has this intense coloration.

Andy Warhold's 1972

Vote McGovern

poster

Andy Warhold's 1972

Vote McGovern

poster

Then you have Donald Moffett’s Reagan image, He Kills Me , which was a response to what was perceived as the violence of Reagan at the height of the AIDS crisis. We’ve announced our upcoming Laura Poitras exhibition, and she’s an artist who we have a history—she was in the Whitney Biennial in 2012—and who’s known largely as a documentary filmmaker. She wanted to explore a way of pursuing her art in the museum’s context, and so this is an opportunity for her now to develop ways of presenting visual/textual images that she’s wanted to create. The subject matter is probably going to be about some of the materials that she’s been researching over the course of many years, even prior to all of the attention that she garnered for the release of information through Edward Snowden and now Citizenfour .

You have artists intersecting with politics all the time in different ways. You think of Barbara Kruger ’s work and her critical consciousness in the way she understands the construction of an image and power structures. I think that’s a strong thread in a lot of the artists in our collection, and to a large extent it testifies to the openness of American culture in our capacity to speak. You were talking about the ethos, and the artist Paul Chan always says “America is an idea.” This elasticity of it as a concept and of the notion of American democracy is continually being tested and debated—it’s an inherent contradiction. I often reference Warhol, and he understood that we’re a culture that loves both conformity and innovation. There’s a push/pull.

In a way, artists are at the forefront of that, and are conscious of the culture. I think you see that in some of the expressions of their passion about certain moments in terms of social injustice or voicing a community that has not been voiced before through visual form. That’s very powerful in terms of people’s capacity to think and challenge people’s thinking. Some artists are celebratory and make art that you retreat into like the way you can lose yourself in a Mark Rothko, but Rothko was also a deep humanist who had a profound belief in the rights of the individual. It can be delivered in many, many different ways, and what constitutes the political is an equally elastic category.