Since the 1980s, the Brooklyn Academy of Music has been renowned for collaborating with eminent visual artists to create exceptionally fine prints. It helps that the institution hasn't had to look far to find the artists it works with. "The community of musicians, artists, and performers is a very closely-knit one, and a lot of these people are friends with each other, and if they weren't collaborating on stage, they were easily in the audience," says BAM curator Dave Harper. In the past, these artists have included David Hockney, Alex Katz, Robert Ryman, Barbara Kruger, Roy Lichtenstein, Kiki Smith, Louise Bourgeois, and many others. To inaugurate a new group of prints that Artspace is offering in partnership with BAM, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Harper about the basics of print collecting, what edition sizes mean, and what to look for in a print.

Tell me about some of the prints in this collection. How were they made?

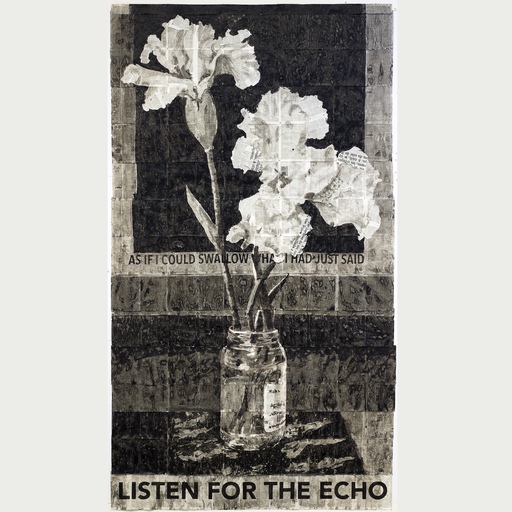

The Jim Dine—which I love because it's very much a Jim Dine, but it's titled Heart of BAM, which really ties it deeply to the institution—is a six-color woodcut, so it's made from six different pieces of wood printed one on top of the other to create an image. Each round, or each essentially each block, would have a different color applied to it and then it would be printed on the paper. It's all done by hand. The Alex Katz is a linocut, which is basically the same thing as a woodblock print except it uses a linoleum block as the release surface. The Marcel Dzama is an archival pigment print that was made by making a scan of the artist's original drawing with a high-resolution scanner and then printing it using archival inks on cotton rag paper to essentially make a limited-edition copy of the original drawing—a process that allows you to own a version of an original drawing that's much more affordable than buying the original. And the same thing with the Deborah Kass, it was done using the same process. The Baechler is a screenprint. I think the last time I tried to get a sense of how many colors there were in that piece I counted at least eight. So that's eight different screens, each one a different color to create the finished image.

So what should people who are just starting to collect art know about prints? Is there anything that they should look for or keep in mind?

I think that you should buy what you like. Find an artist you like and if they make a print and it lets you have a more affordable entry into collecting their work, go for it. People often do shy away from archival pigment prints because there's this idea that they're not as important or as valuable as prints that are made using more traditional processes. But as we get the technology perfected, a lot of times these inks and processes can make works that will last much longer. And although it will never have that same aura of an original work of art, it's still a great way to start collecting because the production costs for making a pigment print from a scan on an archival inkjet printer is much less involved than making a print, an etching, a screenprint from a master printer. Those are much more expensive.

Why do artists make prints? So many of the artists who are highly regarded for their prints, like Alex Katz and Jim Dine, are primarily painters. What draws them to the print medium?

Well, printmaking has its own language, has its own look. A painting and a print of the painting never look the same. There's something different about the way the surfaces work—the way that the materials get different kinds of effects—that attracts a lot of artists. Also it's nice to be able to create multiples because it creates more affordable works. Generally a multiple will be much less expensive than a unique painting. For example, an Alex Katz painting probably will cost you five or six figures at least at this point, and the print will be in the four figures, which is much more approachable for a lot of collectors, especially collectors who are just starting out. A lot of people, myself included, like to collect prints and works on paper because they're not only affordable but there's just something nice about works on paper as opposed to works on canvas. You can get a whole different range of visual languages out of different kinds of paper, different kinds of processes, if it's a screenprint, an etching, or a monoprint or a linocut, or a woodcut, or a lithograph or whatever.

Can you explain how an edition number affects a print's value?

Well, the smaller an edition number is, the more rarified the print will be, of course, because there are less of them. And works on paper tend to deteriorate much faster than other things like sculpture—it's a much more fragile medium, and if they're not well taken care of they can get bleached or get acid damage if they're not archivally framed—and so over the years there are fewer and fewer available from the same series. And, of course, there's inherent value in having less and less and less of an edition of a work. You know, prints are often limited to only several in an edition, and the lower the edition size the more valuable it will become if people are still collecting that artist down the line.

What about etchings or other prints made with an intaglio process, in which the surface of a metal plate is incised and then run through a press to create an image? Today you can get a second-run print of an original Rembrandt etching—how does that compare to one that was made during Rembrandt's lifetime?

That's a different kind of thing, because Rembrandt was working with plates and as you make prints off a metal plate like that using an etching process the plate gets worn down. So the first pressing is always the most valuable because it's the most authentic to what the artist imagined, and as you run that thing through a press time and time again—even if it's Rembrandt himself running it through it—the further you get away from the original and it's not as crisp, clear, dark, and rich as the first one would be. But those plates still exist and people still print from them these days, so you can get reproductions from original Rembrandt prints and they're so affordable because also they weren't supervised by the artist.

What do you mean by "supervised"?

You know, when a print is made, the processes are generally supervised by the artist. All the prints we have were made and/or supervised by the artist, and those of course are more important. But we once did a Roy Lichtenstein print for a fundraiser after he had passed away that was made from the same screens that he used in 1967, and because it was posthumous and was stamped by the foundation rather than signed by the artist that made it less valuable—even though it was his creative idea, his screens, and it could have even been inks he purchased at one point. But, again, because it wasn't made directly or supervised directly by him it wouldn't sell for the same amount as one that was original.

How can you tell that a print was directly supervised by the artist?

Generally, you imagine that if the artist is living and that it's signed and numbered by the artist that it was made with his or her permission. When you're making a print one of the first prints you make is called the B.A.T. print, which is French for "ready to go": Bon í Tirer. That is the one that the artist signs off on to say, "This is what I want it to look like." Then there will be artist's proofs and printer's proofs that they go through, and then eventually it will be the full edition printed, and generally all the prints look identical to each other because the artist set his specifications with the B.A.T. Finally they're signed by the artist and numbered, and in that way you know the artist did have direct supervision. And even our pigment prints that we made with you were all supervised by the artists. The artists got all the proofs and then they signed certificates of authenticity, basically letting the buyer know that, yes, the artist approved the making of this and what you're getting is an authentic work by this artist—rather than a poster. A poster would be something that's probably not supervised by the artist, that you buy in the MoMA store, for the most part is just photographed and then color corrected and made en masse as a picture of a picture rather than an original work of art that's signed and numbered and limited.

And those have the lowest quotient of the "aura" that Walter Benjamin wrote about in his famous 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, where he talked about the special quality given off by original works of art.

Exactly. I think that when talking about "the age of mechanical reproduction" he meant poster prints rather than editioned work. Artists have been making editions and prints for as long as they've been able to figure out how the process goes. Rembrandt made them. Dürer made them. Many, many, many of the greats did them. Picasso made thousands and thousands and thousands and thousands of them.

And if you're a collector who starts out buying prints and then in a few years gets more ambitious, buying paintings and sculpture and other kinds of works, how do those prints fit into the overall collection?

You have to look at it this way: there are plenty of amazing collections that are exclusively of prints. And if you go into museums you can see entire sections devoted to prints, and sometimes people spend their entire lives collecting only prints and building a significant collection out of it. It's not like prints are a training wheel to help a collector move to paintings and sculptures. Sometimes that's the case as you get more ambitious and you have more resources to allocate to collecting, but there are plenty of people—myself being one of them—who will probably collect prints forever because they just love the way that they look and the way that they feel and the way that you know the different kinds of processes and the marks and lines and forms and textures you can get from the different ways prints are made.

So what do you look for in a print personally?

If there's a certain artist whose work I've been following, whose work I support, when he or she makes a print I try to grab it up, because they're usually limited. But I mean I look for all different kinds of things depending on who I'm looking at. But everyone has their own kind of aesthetic, and I think what you should look for is a subject that you like, in a palette that you like, in a size that is manageable for the walls that you have for hanging art, and something that when you look at it it makes you happy.

So edition size is not the first thing that you look at?

No, I don't ever think about edition size. I don't think it's important. I mean, when editions are made the size is determined from a number of factors, some of which might affect the value in the long run. But I'm not looking at collecting as an investment—I'm looking at collecting as a hobby that makes me happy because I like to be surrounded by art all the time. Maybe if I was investing in it as something to sell down the line I would be thinking about the size of the editions, but really I'm looking for images I like that I want to live with.

Another myth too is that a lower edition number is more valuable, that if you have edition number 1 of 10 it's more valuable than 10 of 10. I've never seen any proof of that. But people do collect prints of specific numbers because they have an attachment to that number. Sometimes there are runs of prints that we've sold where all of the numbers are available except that 25 is sold randomly in the middle, and that's because somebody's called and said, "Well, I always try to buy number 25." Every collector has their own little way of doing it. I think the most important thing is to find art that you want to be around. It's been made for the pleasure of our eyes, and that should be the first thing you think about when you look at it. Does it make you happy when you look at it? Does it make you think? Does it make you react in a way? Does it make you want to sit and spend time and think about what it means or how it was made or why it was made? Those are the most important things.

Expert Eye

BAM's Dave Harper on Collecting Prints