At age 16, Phillip March Jones took a detour from a family road trip to visit the Georgia home of the Reverend Howard Finster, the Baptist minister and visionary artist known for his proselytizing paintings and elaborate found-object sculpture garden. “As an aspiring artist in high school, I was really enamored with him,” Jones recalls. “Here was a guy who was unafraid to use any kind of material in any kind of way, who was definitely on his own track.” Thus began a life and career in outsider art, as a gallerist, foundation director, and an artist with an eye for the Southern vernacular.

Seven years ago Jones founded Institute 193, a nonprofit contemporary art space and publisher, in Lexington, Kentucky. While running that gallery, he published his own artist book (Points of Departure: Roadside Memorial Polaroids, The Jargon Society, 2012) and became the inaugural director of the now-prominent Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an organization created by the pioneering Southern collector Bill Arnett to preserve the work of self-taught African-American artists—an undertaking soon to be celebrated in an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. An opportunity to open a New York branch of the Paris-based gallery Christian Berst Art Brut brought him to New York a few years later, and in December he joined Andrew Edlin Gallery (one of the city’s top dealers in outsider art) as it settled into a new home on the Bowery right across from the New Museum.

As he prepared for the 24th edition of the Outsider Art Fair, opening next Thursday at the Metropolitan Pavilion, Jones talked with Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg about the current breakout moment for Souls Grown Deep (and outsider art generally), the particular challenges of representing artists who don't seek attention, and why interest from major museums and collectors is just the beginning.

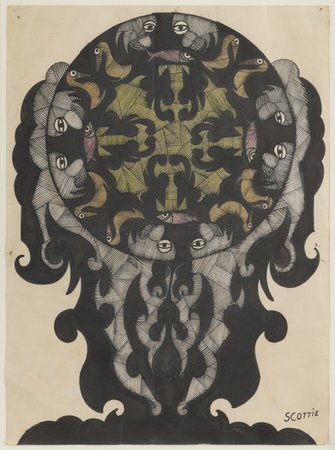

Scottie Wilson, Untitled (Circle Atop Fountain), n.d.. Ink on paper, 15 x 11 inches (38.1 x 27.9 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

What drew you to outsider art, and specifically to the self-taught Southern artists championed by Souls Grown Deep?

Well, I’m Southern—I grew up in Kentucky, and went to college in Georgia. So, my familiarity with that culture and that work is really how I came to meet Bill Arnett of Souls Grown Deep.

I met him through the artist Dinah Young, who at the time was in her late 70s, living in Newbern, Alabama. She’s really invested in landscape—in the contemporary sphere you could compare her to Richard Long, or Robert Smithson. When an animal died on the side of the road she would bury it and create a kind of grave for it, and that grave would reflect the physical characteristics or the spirit of that creature. When a tree came up, she would create a kind of structure around it to welcome it into the world. I used to hang out with her, and make pictures of the work and talk to her. I didn’t know that that had already kind of been done—she said, “Why don’t you call my friend Bill?”

Souls Grown Deep has had an amazing couple of years, with a major gift accepted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and big traveling shows of artists including Thornton Dial—the culmination of many decades of scholarship and outreach by the Arnetts. What was it like working there, as the art world finally started to embrace the foundation’s mission?

Bill is a really interesting guy—he’s been a tireless advocate for this work. Most people don’t know this, but he started out with a strong interest in non-Western art. He came to this work after looking at all these other regions and understanding that where you have great dance you have great painting, where you have great painting you have great architecture, and you have all these components of culture. And being from Southern Georgia, he understood that African-American musical and dance culture was well known but that the visual art wasn’t being celebrated and documented. So he went out to find it, and did.

When I joined Souls Grown Deep, it was a transitional phase for the organization. There were a lot of different initiatives on the table. In those few years we did a great show at the Frist Center in Nashville, and the Indianapolis Museum of Art show of Dial’s work that traveled to four different American museums and was written about in Time magazine, the New York Times, everywhere.

For whatever reason, people in this part of the art world finally got it. Bill has always gotten it, and he’s pushed relentlessly for it, but for whatever reason, through our collective efforts, and maybe the universe, things kind of fell into place. Unfortunately, many of the artists are no longer living.

Or they’re very old, and experiencing this newfound recognition only at the ends of their lives and careers.

Yeah. I mean, Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, some of the Gee’s Bend quiltmakers, Joe Minter—that’s kind of it. Most of those artists started passing away at the end of the '90s and early 2000s.

Mary T. Smith, Three Figures, 1987. Paint on plywood panel, 12.5 x 23.5 inches (317.5 x 596.9 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

Mary T. Smith, Three Figures, 1987. Paint on plywood panel, 12.5 x 23.5 inches (317.5 x 596.9 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

This is a kind of outsider art that’s very specific to a particular time and place.

That was always Bill’s thesis, that African-Americans felt not only the right but also the responsibility, in the wake of Dr. King’s death and in a changing world, to express themselves in the open. Everything had always been done secretively, in private.

The phrase “secret language” comes up frequently in the Souls Grown Deep literature.

In school, they teach you about some of the coded African-American language in the music, the gospels. But it’s so obvious that these things were also present in the visual culture, in those early sculptures. If you look at Dinah Young’s work, it’s very much in that older tradition of roadside installations and very subtle meditations on life, death, the nature of the universe, the cataloging of culture—all the things that art is about, but in a very subtle and hidden way.

Within the catchall term “outsider art,” you have all these different concepts of isolation. You have the isolation of the mentally ill, as highlighted by Dubuffet’s Art Brut, and the isolation of Souls Grown Deep artists, which has more to do with socioeconomic factors, racism, and the legacy of slavery.

It’s different. The word “isolation” gets a bit tricky there, though, because a lot of the artists I worked with weren’t people who lived in isolation.

Maybe “alienation” is a better word?

Certainly, but then, that’s in the African-American experience. What’s important to remember is that a lot of those artists were, and still are, functioning and essential members of their communities.

Yes—what I’m getting at is, though, is that on the whole the art of Souls Grown Deep and the art of, say, Dubuffet’s Art Brut comes out of different experiences. How do you negotiate these and other differences, since you work with artists from all over the “outsider” spectrum?

I’ve always worked with all kinds of different artists. Even at Souls Grown Deep, someone like Royal Robertson, for example, probably did have some mental health issues. But Thornton Dial, the Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers—all of these artists are making work in a cultural tradition, have their own very specific aesthetic experience, but they’re also making other references. Thornton Dial, for example, was able to take the African-American yard show and translate it into paintings, assemblages, whatever you want to call them—these large works that you could hang on the wall. He was able to translate that experience in a way that could be digested by big museums. A big museum isn’t going to take Dinah Young’s or Lonnie Holley’s yard, for the most part, but they might take a Thornton Dial painting.

At Institute 193 we worked with quote-unquote “contemporary” artists, emerging artists, self-taught, Art Brut—there’s all these different labels, and they all have their own pitfalls. But in my role here, as the director of the gallery, we show artists from that entire spectrum.

As you were saying, a museum will take a painting but they won’t take a yard installation—what are some of the other difficulties or concerns of bringing this kind of art into a big encyclopedic museum, or even a museum that’s more focused on modern and contemporary art?

The work that I handled at Souls Grown Deep was very specific. It was essentially created over a 30-to-50-year period, and a lot of it, in the case of someone like Dinah Young, is composed of site-specific objects and references in the landscape. But at the end of the day these things should be presented as artworks, which they are. So I don’t know why it would be a problem for an institution to install a work by any of these artists.

As at any responsible university or museum, there’s a context that should be delineated on a wall label or in a catalog. But there’s no reason to put a quilt from Gee’s Bend on a bed in a gallery or museum. It can be hung on the wall, just like something from Eugene Von Bruenchenhein. In our current show by that artist, we have things were all made in his very small house in Wisconsin, and at the time he was firing his ceramics in the oven and there was dust everywhere, but we don’t need to re-create that whole environment. We can just hang the painting on the wall. It’s a very striking object from the mid-century in this country that reflects all of the collective anxieties of the atomic age, the primordial stuff that could arise from a nuclear explosion—the kind of stuff people thought about in the ‘50s and ‘60s at the height of the Cold War.

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Untitled (February 19, 1955). Oil on board, 17 x 15 inches (43.2 x 38.1 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery and Estate of Eugene von Bruenchenhein

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Untitled (February 19, 1955). Oil on board, 17 x 15 inches (43.2 x 38.1 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery and Estate of Eugene von Bruenchenhein

So curators ought to think about how to contextualize a work like this with, say, other artworks from the ‘50s and ‘60s, as opposed to just putting it in a timeless “visionary” category.

Of course. People don’t realize this, but Von Bruenchenhein applied for an N.E.A. grant at one point. He wanted to be recognized. Now, for a lot of different reasons he didn’t have the ability to market himself, to brand himself, to contact the galleries. But he was a published poet—he was in the American Voices anthology in the mid-‘30s. He had some contact with the outside world.

That brings up another question: You’re working with artists who are not always able to market themselves, in the way that someone coming up through the M.F.A. system is trained to do.

Well, sometimes they can’t and sometimes they won’t. It’s a case-by-case basis. Someone like Judith Scott, who was deaf—there’s a lot of reasons she wouldn’t be able to do that. And other people are just so involved in the works they’re creating that it’s not really part of their reflective process.

A lot of the art we show is created for very personal reasons, usually in private. Often, the artists create worlds they wish to inhabit. Maybe sometimes they don’t know that they aren’t inhabiting them—maybe they live within that work, or maybe the relationship to the work is more important, or real, than the relationships they have in our real world. I think someone like Henry Darger very clearly lived more in his work, his drawings, than in Chicago.

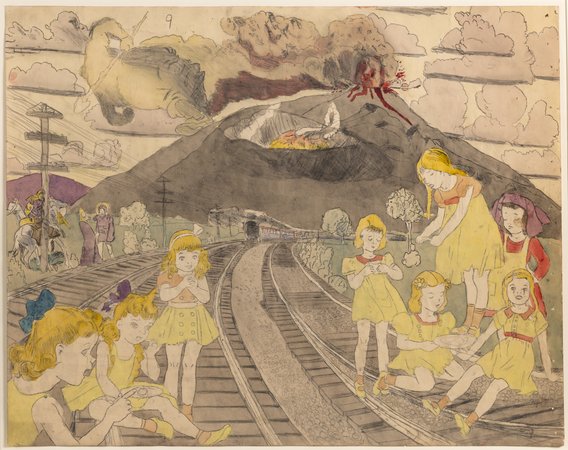

Henry Darger, Untitled, n.d.. Watercolor and pencil on paper, 18 x 24 inches (45.7 x 61 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

Henry Darger, Untitled, n.d.. Watercolor and pencil on paper, 18 x 24 inches (45.7 x 61 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

So this makes you a very important intermediary between these worlds. It’s a little different from being a more general dealer of contemporary art.

It’s completely different, and it poses a lot of really interesting questions—ethical, moral, logistical. It’s all very specific—dealing with someone like a Thornton Dial, as a foundation director, is distinct versus dealing with the estate of Eugene Von Bruenchenhein. The good news is that for a lot of different reasons, this work is now being shown at the highest levels of both the commercial and institutional art worlds, whether it be at the Metropolitan Museum in the Souls Grown Deep show coming later this year or recently in shows at the Hayward Gallery and prior to that the Venice Biennale. The New Museum has been showing works in this field for decades—they did a Howard Finster show in the ‘80s.

If you had to pick just one bellwether event, I think the 2013 Venice Biennale curated by Massimiliano Gioni was huge in terms of exposing a mainstream contemporary art audience to this material.

The facts on the ground have always been there—Dubuffet, Breton, all these guys were very interested in the work, showed it, and collected it. But I don’t know that people really knew that—I think it was a revelation for a lot of collectors and institutions, as was the Dial show. We got a lot of calls right after that, and some big press.

For the artists who are still living, what does this sudden exposure do? There’s a kind of myth that these artists are impervious to fame and market pressures.

Well, it’s a case-by-case basis, of course. But look at someone like Lonnie Holley—people started coming back to his visual art through his music that was produced not so long ago. All of a sudden he’s in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, he’s performing at the Whitney in the “Blues for Smoke” show with these really hip bands from Brooklyn. And then James Fuentes shows the work, and then he has this solo booth at Frieze. Now he’s going to be in the Met. But Lonnie is Lonnie. He’s walking around making things, engaging with people, bending wire, and singing. I think whatever changes have occurred in Lonnie’s life have been positive, but the work has not changed. The only thing that’s changed is that Lonnie now has a bigger platform and more resources to take care of himself and his family.

And somebody like Dial, who has been recognized for a long time—he had a solo show at the New Museum 20 years ago—it’s a different case. But with all that recognition, he still works in the same town in the same way. He’s still surrounded by his family. He lives a qualitatively better life, financially. But the guy has been on a really straight path forward.

As dealers in this field we have a greater responsibility to the artist, because frequently you are the one who is making a lot of the decisions that the artist would make. When I work with a contemporary artist, they’re present for the installation—they’re doing all these things that for the most part the outsider artist is not engaged in.

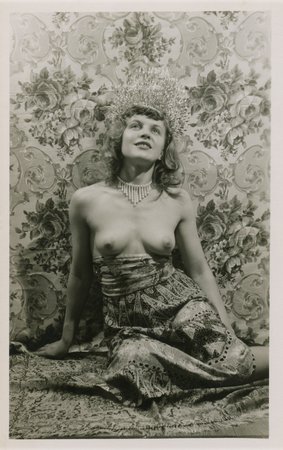

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Untitled, (1940s). Gelatin silver print, 4.25 x 2.5 inches (10.8 x 6.4 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery and Estate of Eugene von Bruenchenhein

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Untitled, (1940s). Gelatin silver print, 4.25 x 2.5 inches (10.8 x 6.4 cm). Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery and Estate of Eugene von Bruenchenhein

What about the process of discovering these artists—how has that changed in recent years, with the new levels of access and exposure afforded by digital platforms?

By definition these artists aren’t seeking representation, so that part of the digital equation doesn’t really exist. Sometimes there’s a family member, or someone who might be advocating on behalf of a particular artist. But in my experience over the past decade or so, most of the artists that I have championed have come to me through word-of-mouth. A lot of people say, “Hey, I saw this thing, and I thought you might be interested.”

But it’s obvious that the digital realm is really impacting the contemporary artists I work with—they have to be their own brand consultants. Which is unfortunate because any time you’re spending on that, you’re not developing your own craft and ideas.

What about the new opportunities for the public to discover this art? For instance, a 16-year-old today who wants to learn about Howard Finster can go online and be completely immersed in material.

It’s just the tip of the iceberg. What is really needed is further exploration of these artists and ideas, both digitally and in terms of collections. This work, the great outsider and self-taught artists—they all belong at the highest levels of institutional collections and university collections. It’s so obvious.

Is that the next step in this renaissance of outsider art?

It’s happening now. These regional museums are all looking at this work with fresh eyes, and trying to figure it out. Because it’s not really taught in the way that it should be, in schools and educational programs.

That’s kind of exciting too, because established curators can come to this material and, knowing the history of Modern or 20th-century art, they can look at the work and maybe find the references in the other direction.

So it’s crucial to have more scholarship, along with more market attention.

It’s a big part of it. As the director of a commercial gallery in New York City that’s not exactly my responsibility, but I’m certainly rooting for it and trying to be a resource for those institutions and people.

Are you seeing more interest from new collectors of outsider art, people who might be branching out from blue-chip contemporary?

Absolutely. That’s been the trajectory for a long time, but it has been accelerated by some big sales at some auction houses like Christie’s, and also by some institutional interest. These big museum shows that feature this work obviously puts this work on the radar. I visited the Biennale with a big contemporary collector—we went around and he saw Guo Fengyi’s work for the first time. The guy only collects blue-chip contemporary work—he saw this and had no idea what it was, and ended up buying one and is now dipping into this field.

The biggest advocates of this work, if you go back and look at the provenance on some of the major outsider works, have been artists. Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson owned great Martín Ramírezes. Roger Brown has been a great collector of this work. It has always been collected by major artists and thinkers, but I think the rest of the world is finally getting the message.