Even in the face of "more convenient," screen-based technologies, the tactile pages of the humble tome have proven themselves against the test of time, asserting themselves as a ubiquitous symbol of culture and civilization. It's only natural that artists have adopted the book as a medium and have gone totally wild.

In Phaidon's new release, Artists Who Make Books , rare book dealer and publisher of PPP editions, Andrew Roth, along with Printed Matter 's Board President Philip E. Aarons, and artist and writer Claire Lehman, compile together 32 prominent international artists (including John Baldessari , Sophie Calle , and Sol LeWitt ) who have continuously used books as vital parts of their creative practice, experimenting with the medium's form, function, and history. From underground, D.I.Y. zines to high concept art objects, these artists' books will have you flippin'!

[related-works-module]

Among these book-bound creatives is multi-media artist Tauba Auerbach . Engaging with numerous scientific and formal topics such as symbolic systems, visual perception, and the structural significance of patterning, Auerbach's diverse output includes rainbow-hued trompe l’oeil canvases, hand-wrought glass helices, elegantly calligraphed text-based drawings, and (of course) books—from zines to technically advanced sculptural volumes to unique takes on the exhibition catalogue.

In 2013, as a way to avoid the typical art-market mechanisms of dealers, galleries, and price appreciation (Oh my!) Auerbach founded Diagonal Press, a publishing project devoted to producing books in open editions. In the following excerpt, Editors Philip E. Aarons and Claire Lehmann speak with Auerbach on the value of books and bookmaking to an artists practice, as well as the hurdles that come with running your own press.

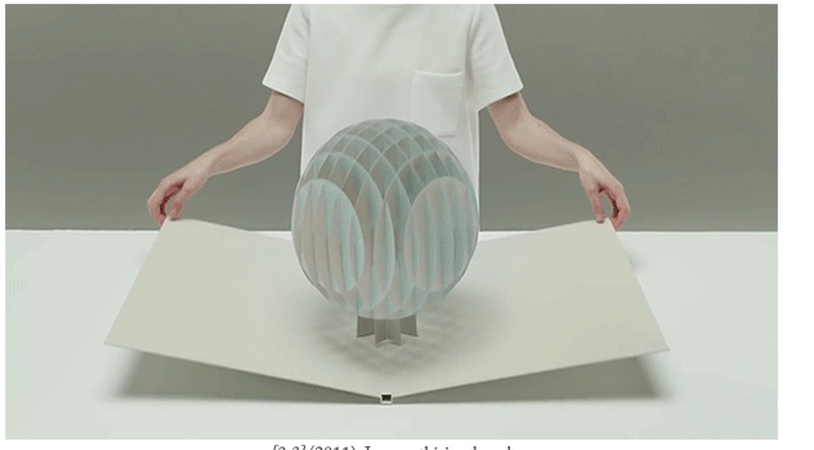

[2,3] (2011). Image: thisiscolossal

Philip Aarons: Creating books has clearly been important to you throughout your career. When did that interest begin?

The first books I made were when I was a kid, bored in my parents’ office, waiting for them to be done at work. I had office supplies to amuse myself with—business cards and hole punches and stickers for their Pendaflex files—so I made a lot of books out of those things. My dad showed me how to sew a book with signatures at some point. I still have it: it has a hard cover wrapped in paper with fruit all over it and a metallic red spine. He really did a good job showing me, but I don’t remember how to do it anymore. Then in my teens and early twenties, everybody around me was making and trading zines, mostly about punk music or graffiti, and I made zines as a way to show my drawings, because I had no other way of doing so at the time. I was never content with folding photocopies in half and stapling them, so for my three-issue “periodical” Twentysix (2003–4), named for the number of letters in the alphabet (I was working as a sign painter at the time), the first one had a giant rubber band as a binding, the second one was sewn on a machine, and the third one was printed with a Gocco [a Japanese silk-screening kit] on heavy museum board that I hand cut and wrapped with a printed band. It was an insane amount of effort for something I think I sold for five dollars, if I ever sold it at all. I mostly just gave it away. I was doing that for a while, and then when I started having exhibitions, I’d often make books to include in some way. There was a book-trading piece in one of my first shows in San Francisco, and an alphabetized Bible in my first show in New York. At some point in 2007 or 2008, I started working on a giant pop-up book called [2,3] , which didn’t come out until 2011—it took a long, long time. I started it as a lighthearted outlet for some of the ideas I was thinking about while painting, such as making the distinction between different dimensional states more porous. I got really into the paper engineering part of it, and it became mostly about that for me—the pleasure of making it work.

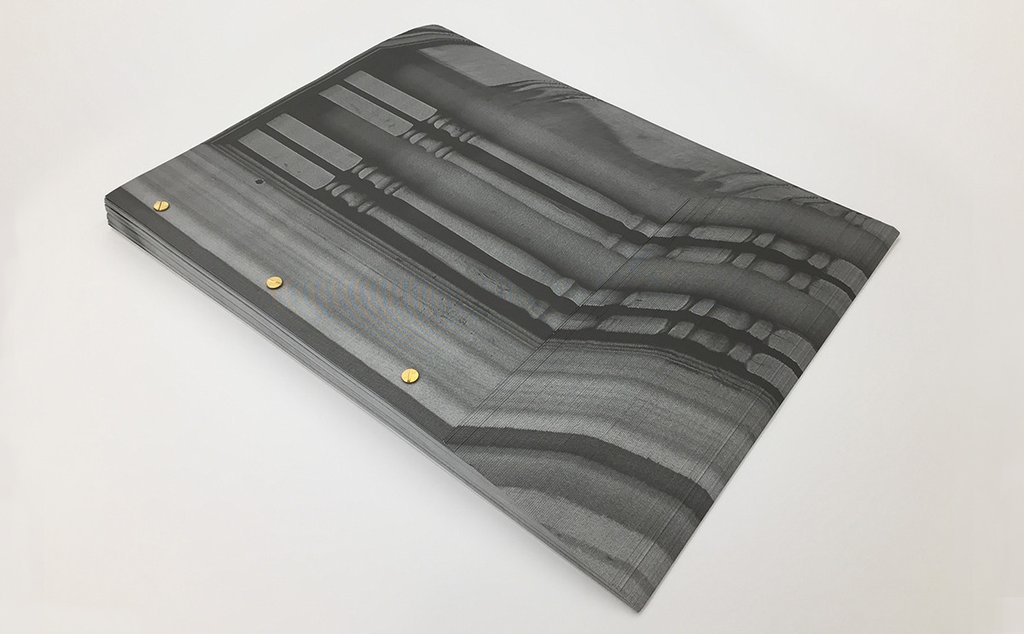

Then I began making a number of books that were really sculptures, but they used the book as a format to riff on. The books Marble (2011), Wood (2011), and Bent Onyx (2012) were made by taking a block of solid material, scanning it, sanding off a paper’s worth of thickness, scanning it again, sanding off another paper’s worth of thickness, over and over, printing all of the scans and binding them together to make a three-dimensional copy of the original material, which had disappeared during the sanding process. The edges of these books were hand painted so that the veins or grain of the material would match up with the printing on the inside. In some ways these projects felt like a success, but I wasn’t satisfied with the way they were operating as books. Part of the beauty of the book is the way it’s distributed, how it moves around the world, and these didn’t participate in that in a way that felt right to me. These books obviously couldn’t be widely accessible, because there was so much handwork involved.

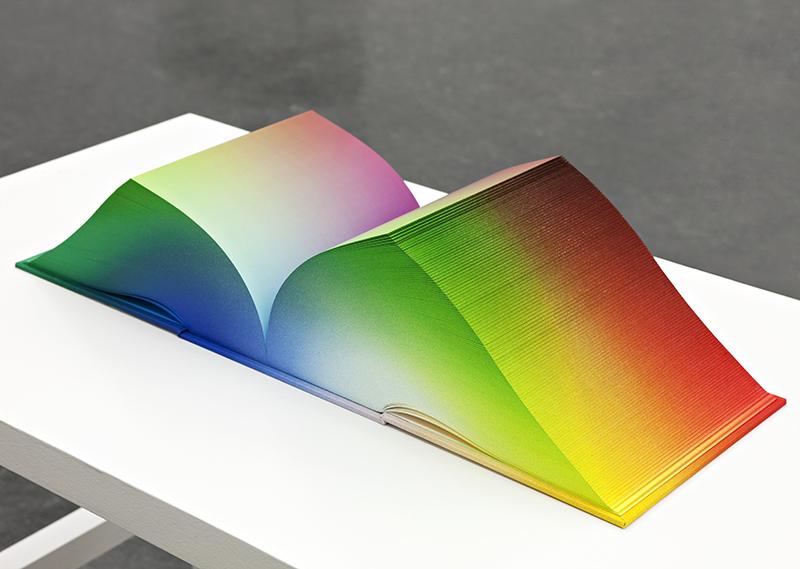

RGB Colorspace Atlas (2011). Image: Sight Unseen

RGB Colorspace Atlas (2011). Image: Sight Unseen

Claire Lehman: What were their edition sizes?

Eight to ten—they were so laborious to make! I was painting edges on the Marble and Wood books for a year and half. Just now I’m sending the last of these books to someone else for hand-painting, because there are a few left and I don’t have time to complete them on my own. It pains me to hand it over to someone else; I’m very conflicted about it. Another book from that time, RGB Colorspace Atlas (2011), was an even smaller edition, just three copies. Each edition is a set of three cubic volumes that model various ways of slicing the RGB color space—the theoretical color model that spatially plots hues by assigning each of the three axes of the cube to red, green, and blue light, respectively. The surfaces of the pages were digitally printed, and I airbrushed the covers and the edges of the text blocks, which I had to do very slowly so that they would never get wet enough to stick together or warp.

CL: Did you collaborate with scientists or fabricators to make those books?

At certain stages, yes, but I tried to do everything I could in my studio. Marble came first, and my studio manager and all-around amazing assistant, Chelsea Deklotz, did a lot of the sanding. We purchased an oscillating flat lap, which is a machine that vibrates a big level surface that you put sanding grit and water on and then place the stone on top. It shakes, and the stone’s own weight presses it against the grit. We had that running in the studio for about a month and a half. I had a very specific way I wanted that book to be bound—so that it would look like a slab—and I didn’t have the skills or the equipment to do that: a heat press, a very large guillotine, those kinds of things. So I connected with this extremely talented master bookbinder, Daniel Kelm. That was a great collaboration because we’re very like-minded people—he used to be a chemistry teacher, and he has a scientific glass collection—and I enjoyed spending time with him. I asked him to explain every single step to me, so we had these extensive conversations about paper grain, adhesives, and so forth, and I learned a lot from him in the process. But in terms of those works functioning as books, like I said, I was unsatisfied, and I started thinking about why and what that meant. Around 2012 or 2013, I was at a point in my career where I was feeling like, all right, I’ve moved in this straight line and things have gone “well,” but there are challenges and moral conflicts in the profession of art that I hadn’t predicted. I entered my career young and with very little knowledge of how the whole business worked—young artists are so savvy today, but I wasn’t, I knew nothing—so I hadn’t built my career with a lot of intentionality. I had just been humming along, totally focused on making drawings and paintings, and the rest felt like it was just kind of happening to me. But I came to a point where I realized that unless I swam upstream, I’d end up only speaking to the wealthiest people in the world or, even worse, acting as an employee to superrich collectors who bought my work just to resell it. I saw that many of the people buying my work didn’t give a damn about the work itself. I found myself becoming cynical, so I spent a lot of time thinking about what I could do to address the position I was in, and I wanted it to take the form of building something rather than taking something apart. So that’s when Diagonal Press started. It’s increasingly important to me. More and more of my attention is drifting to the press.

Marble (2011). Image: Letterology

Marble (2011). Image: Letterology

PA: The move from being a do-it-yourself bookmaker to establishing a press suggests larger edition sizes or even the possibility of publishing other people’s books.

Bigger editions, yes. One of the biggest objectives of the press is to take certain things that I don’t like about the art market out of the equation, and hopefully out of the transaction of sharing my work with others. With Diagonal, everything is an open edition and nothing is signed or numbered, so the things I make don’t really increase in value. Someone could put the publications on eBay, I suppose, but if anybody searches the Internet for a second, they’ll see that they can purchase the same thing from me at the original price. Also, no one knows how much of each thing was made, and nothing is signed, so no copy is more “special” than another copy. I want the interest in the work to be genuine and true, so I’ve tried to create the circumstances for that. When I was first turning the idea of a press over in my mind, I talked to James Jenkin [former director of New York–based nonprofit Printed Matter] about it, and he said, “If you do this, it should be a commitment. If you establish something, you should be committed to doing a certain number of publications every year, not just a single publication for this one New York Art Book Fair.” At first that kind of scared me, but it was good advice. I thought, yes, I do want to make that commitment; I have a lot of ideas that could take the form of publications. I had all of these ongoing projects that I hadn’t known what to do with, like all the typefaces I’d designed over the years for friends’ album art or for the calendar that I used to make every year and give away as a gift. I had always wanted to gather and present them in some way but hadn’t come up with the right way to do it. I didn’t want to sell them as fonts for people to use, for instance, but now, through the press, I publish posters that are specimens of those typefaces. They’re more like documents of letter logic than designs that you can implement for packaging or whatever. And Diagonal Press also makes other things, like mathematical models, drug paraphernalia, symbolic badges, and I’m working on some flags. It’s kind of a catchall for these other ideas that I thought would make more sense as multiples than as one-of-a-kind forms.

CL: Dieter Roth famously said he only made art so that he could fund his bookmaking—he wanted to put his books in the world, but he had to have another area of production to support it. Given all the materials and labor and studio time that goes into producing Diagonal Press books, does it function financially on its own?

No, it’s a money pit, and I don’t care. I only come close to breaking even, but that isn’t accounting for my time. But I can spend that time because I also sell paintings, so I guess it’s very similar. It’s not a priority to make it work financially, other than the fact that I would like to prove to myself that it’s possible to have a viable business that isn’t compromised—and I see now that it is very, very hard to do something completely on your own terms. I’m lucky to work with two excellent art dealers, but still, I wanted the press to be totally autonomous. Of course, I discovered that there is a huge reason why dealers exist—a lot of time and work goes into the mechanics of making something and getting it out into the world. So I have a great part-time employee, Ada Potter, who helps me with the press and is doing most of the production now, like the binding and rubber stamping. I just got a guillotine, so the book I’m making for the 2016 New York Art Book Fair is a weirdly shaped guillotine-sliced book. It will be professionally printed, but I’m cutting each one myself here. When I was doing the cutting tests, I realized that it was impossible for me to make them all the same, so I decided to lean into that and make them really vary. It’s the first publication I’m doing as “open edition, all unique.” So far, I’ve kept everything completely the same so that no one copy is more valuable than any other. I’m hoping that if these are all different, the edition will function the same way. On the subject of editions having variation, I have a slightly difficult situation at the moment. For two publications—the books that accompanied my most recent exhibition [ Projective Instrument , 2016] at Paula Cooper—I used vinyl for the covers. I made them in the winter and now it’s summer, and the vinyl has become wiggly and weird! So now I have to change how I’m making these two books. And I have another book that we were binding with yellow tape all along, but they discontinued the yellow tape—so this publication has to change, too.

PA: So they become, de facto, limited.

Yes. And I can’t control these circumstances! I have to roll with them. That’s part of the meaning of “open,” but at the same time, it poses a dilemma for me. For the edition where the vinyl covers are warping, if I change the cover material going forward, then the original version, which is flawed and in my opinion worse—

CL: —becomes the collectible.

Yes, which is so annoying! I haven’t figured out how to deal with it. I mean, sometimes change needs to happen. And what if I want to make changes voluntarily, to improve on something? This type of progress can and should continue to happen. The last thing I want is for my thinking about value and distribution to hinder the creative part or prevent me from improving quality. That would be another way of letting those forces win.

CL: How many books has Diagonal released?

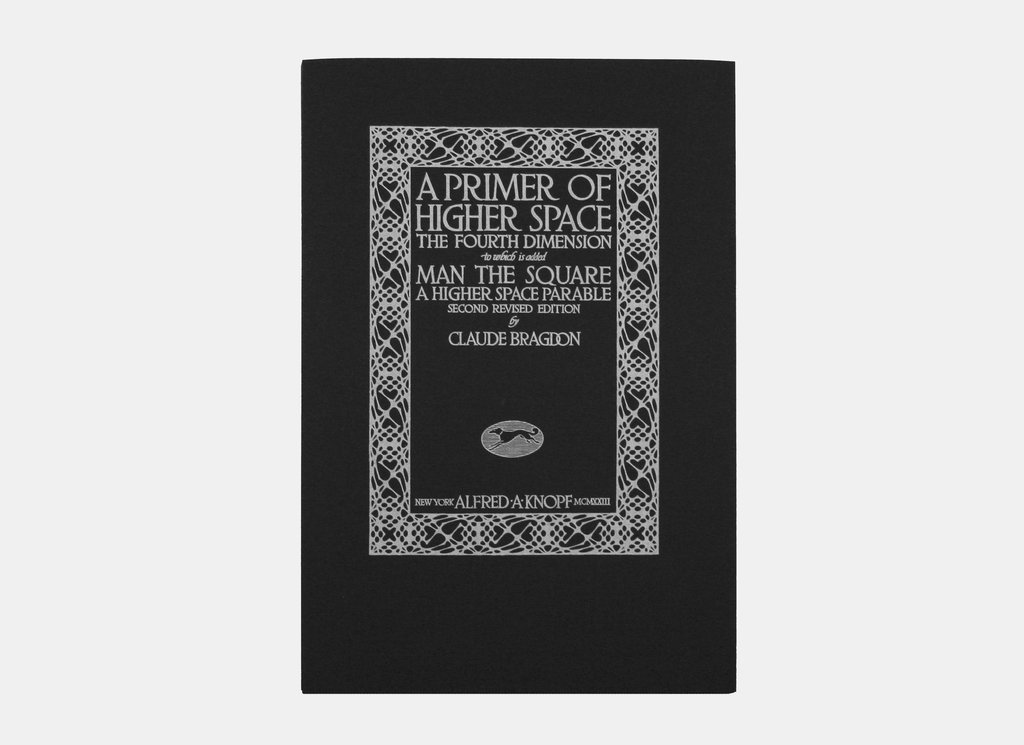

Nine at this point. There will be one more by September 2016. The last two publications, the ones with the vinyl-cover issues done in conjunction with the Projective Instrument show, are the first Diagonal Press works that are not my own. They are republications of books [ Projective Ornament (1915) and A Primer of Higher Space (1913)] by the architect and theosophist Claude Bragdon, who wrote extensively about four-dimensional space. I feel a kindred connection with him, and I hope he would have approved of the way I remade his books. He was also a publisher, and his book designs were excellent.

A Primer of Higher Space (1913/2016). Image: Diagonal Press

A Primer of Higher Space (1913/2016). Image: Diagonal Press

...

CL: With many of your books, you reveal visual experiences that are typically unavailable in normal dimensional space or time: a shape transforming from two dimensions to three in [2,3] ; the inside of a mathematical color space in RGB Colorspace Atlas ; the interior of a solid material in Marble, Wood, and Bent Onyx ; the transitions of a video dissolve in Saccade 1, 2, and 3 (2013). I’m curious to know whether you come up with the idea of making a book first, or whether you initially have an interest in exploring a particular idea, which then dictates the book form.

I think the causality runs in both directions. Usually I have a few ideas that I’m obsessing over, and I seem to always be in the process of learning new production techniques, so often a book appears when those two things converge. I like the challenge of working within “what’s possible,” because usually the answer is “a lot.” For the book that I’m working on now [ There Have Been and Will Be Many San Franciscos , 2016], I’d been thinking about all the consumer-level press equipment that I could exploit, and I had the opportunity to get a guillotine from the folks at Peradam [a small publisher of artists’ books], so I brainstormed about different ways to use it. I also liked the printer LINCO, but their minimum print run is a thousand copies of any plate, usually much too high for me. So I decided to make a book composed of 175 pages of the same image—of a wall in San Francisco—and then shear the stack of prints and cut it in the guillotine at various angles. The result is these kind of stretched-out, spooky shapes. It’s like the ghosts of San Francisco past, little distorted slices in time. I’m sad about my home city right now and this is a little love letter to it. But also, this oddly shaped book is an expression of how perplexing and stretchy I find time in general, and how I think what we are experiencing is just a slice of something more complex.

PA: One of the things I love about your books is that you’re always questioning how we’re thinking about books, especially their linear quality and their dimensional quality. All True No. 1 (2005) seemed to me both linear and circular at the same time. And it’s sort of zine-y in a sense, right?

Yes, I stuck down every piece of tape, wrote every equals sign, Gocco-printed the covers, everything. I think of its logical structure as a Möbius strip: if you follow the path from the beginning to the end, you arrive at a place that is conceptually on the opposite side of the surface you started on, but you never left that surface to get there. Then, if you follow that path around the loop again, you end up on the first side. I like that, typically, a book is a collection of text in lines that are arranged into planes, which are bound into a volume. So there are one-, two-, and three-dimensional features that you’re moving through and interacting with, and there is a lot of opportunity in that. This is why I mess with format and binding so often.

There Have Been and Will Be Many San Franciscos (2016). Image: Diagonal Press

There Have Been and Will Be Many San Franciscos (2016). Image: Diagonal Press

PA: Stab/Ghost is interesting to me as a book form, because it seems as though you’ve given a relatively high degree of primacy to the binding.

The binding is often a key feature because it’s structural and requires some kind of engineering. A lot of the enamel badges that I’m making for Diagonal Press are drawings of these binding structures. It’s fine with me if people treat them like just a “cool shape” or something, but unknowingly, they’re walking around with a symbol of holding together. I like that symbolic idea of binding, particularly right now.

CL: Is it fair to say that your engagement with books has been quietly political all along?

With the exception of the books that I really consider sculptures (like Marble and RGB Colorspace Atlas ), yes. The way I make and work with books is definitely an expression of a certain politics, even if the publications are not explicitly about those politics.

PA: One of the things that I admire a lot about your book practice is that at the New York and Los Angeles Art Book Fairs, you are there presenting your work—manning the booth yourself.

I don’t like how when you become successful as an artist, you become increasingly sequestered from your audience. You find yourself at dinners flanked by collectors rather than artists or other peers. I hate the whole fame game so much. Being at the Art Book Fair is a nice opportunity to speak to all types of people. I end up having conversations with design students who want to talk about fonts, or people who just came because it was a good weekend family activity, and then of course there are librarians and book enthusiasts. I like it, at least for now, and it feels right to put my body in the space as an expression of commitment.

Auerbach at NYABF 2014. Image: MoMa

Auerbach at NYABF 2014. Image: MoMa

CL: Have you ever thought that the press could become your primary activity? Would you ever want to see that happen? Is there a part of you that desires that?

I really love painting. And working with glass. And weaving. And a million other things. I can’t give up making other work, and I think exhibitions can’t be replaced by publications. I like using them together. And also I think that it’s going to be necessary to do that other work if I want Diagonal Press to continue.

PA: That’s one of the reasons bookmaking is so interesting to me—it exists beyond commercial activity.

Yes. It really has to be a labor of love.

[related-works-module]