Celeste Dupuy-Spencer moves between styles, gestures and a history of painting to interrogate the American experience. Hailed by curators and critics as a leading artist of her generation, she's known for her energetic brushwork and incorporating a montage of visual language. Celeste’s paintings grapple with existential questions through figures and scenes that are at once confrontational and tender. Community and more broadly, society - in all its contradictions - is often the protagonist in a body of work that aims to capture the ever-evolving nature of America. Here the painter talks us through five things to look out for in her new Artspace edition When you’ve eaten everything below you, you’ll devour yourself/except in dreams you’re never really free, 2020/2021 . Proceeds from the sale of this edition of 50 will be donated to New York City’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center.

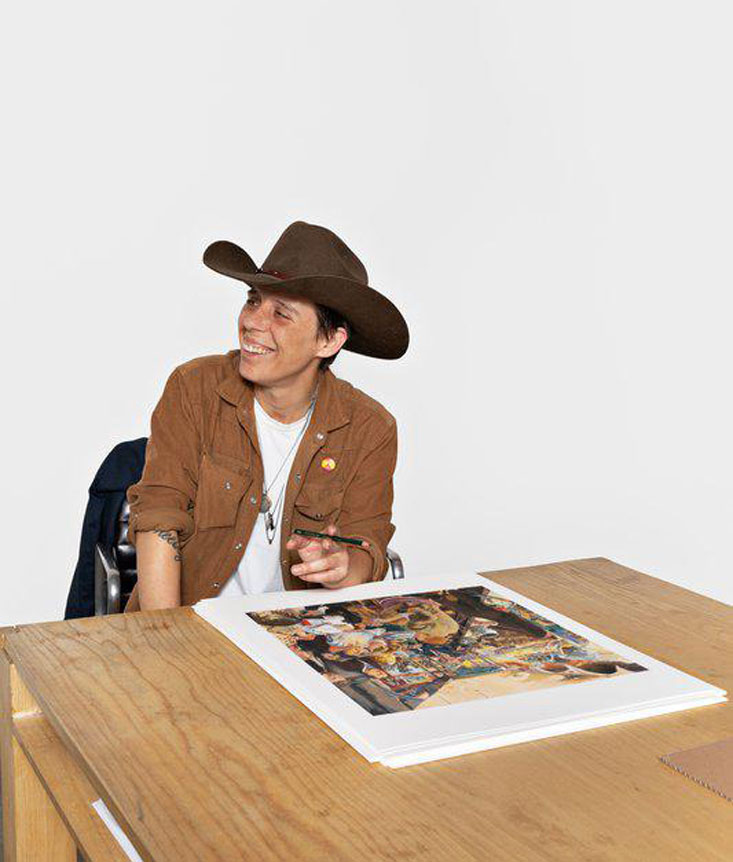

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer - photographed by Dawn Blackman

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer - photographed by Dawn Blackman

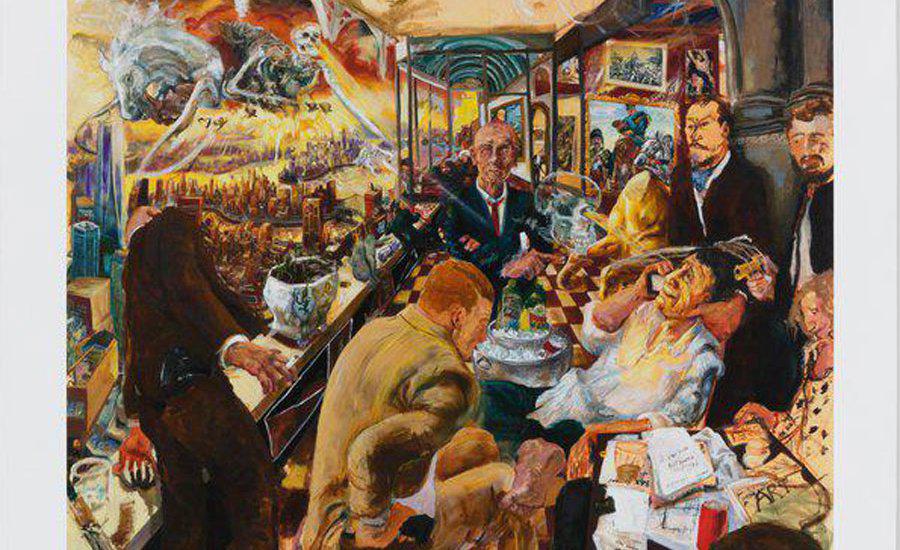

"My paintings are packed with all of this information and there’s literally no way for a person to know, so I’m glad to get the opportunity to pick out a few things in this one. So much of it smashes in and out and it makes total sense to me at the time, but if I don’t write it down, in some paintings - not this one – the ideas can be lost forever.

"When I begin a painting it really starts off as just a basic idea. I don’t actually know if this one started off with this heist scene but then it sort of developed into that. These were the faces that were there within seconds of the painting starting and then they began to tell me where it was going.

THE GUY ON THE PHONE The story I had in my head - whether or not it’s right – is that we’re in a Manhattan loft belonging to the guy on the phone. The woman sitting next to him is his assistant and his wife is in the back in this glass container. He's on the phone at the moment when more rich and powerful people have come to take his life. I'm not certain who he is on the phone with, maybe his mom saying goodbye, or his lawyer signing over his goods to these guys who are going through his art collection and his property. Either way, he’s got his black American express card out - I had to Google what sort of credit card he would have! The people who are alive are probably alive because they’ve done this to everyone beneath them. The title is me reflecting on the fact that once everyone else has been killed or doesn’t have anything that anybody wants any more, that people are not actually going to be happy and relaxed. They’re going to start turning against one another.

The man is in that moment, mere seconds before somebody dies, when they go from pleading to smiling. He’s at this moment when death on the horse is in front of him, shining its lights on him. We’re here a second before the gun goes off essentially. Death is moving the gun to the back of his head. I sometimes wonder whether he’s looking at Jesus come down but what we see on the canvas is just a pale horse with a skeleton on it. A gunman is also peering behind that painting to see if there’s maybe a hidden safe there.

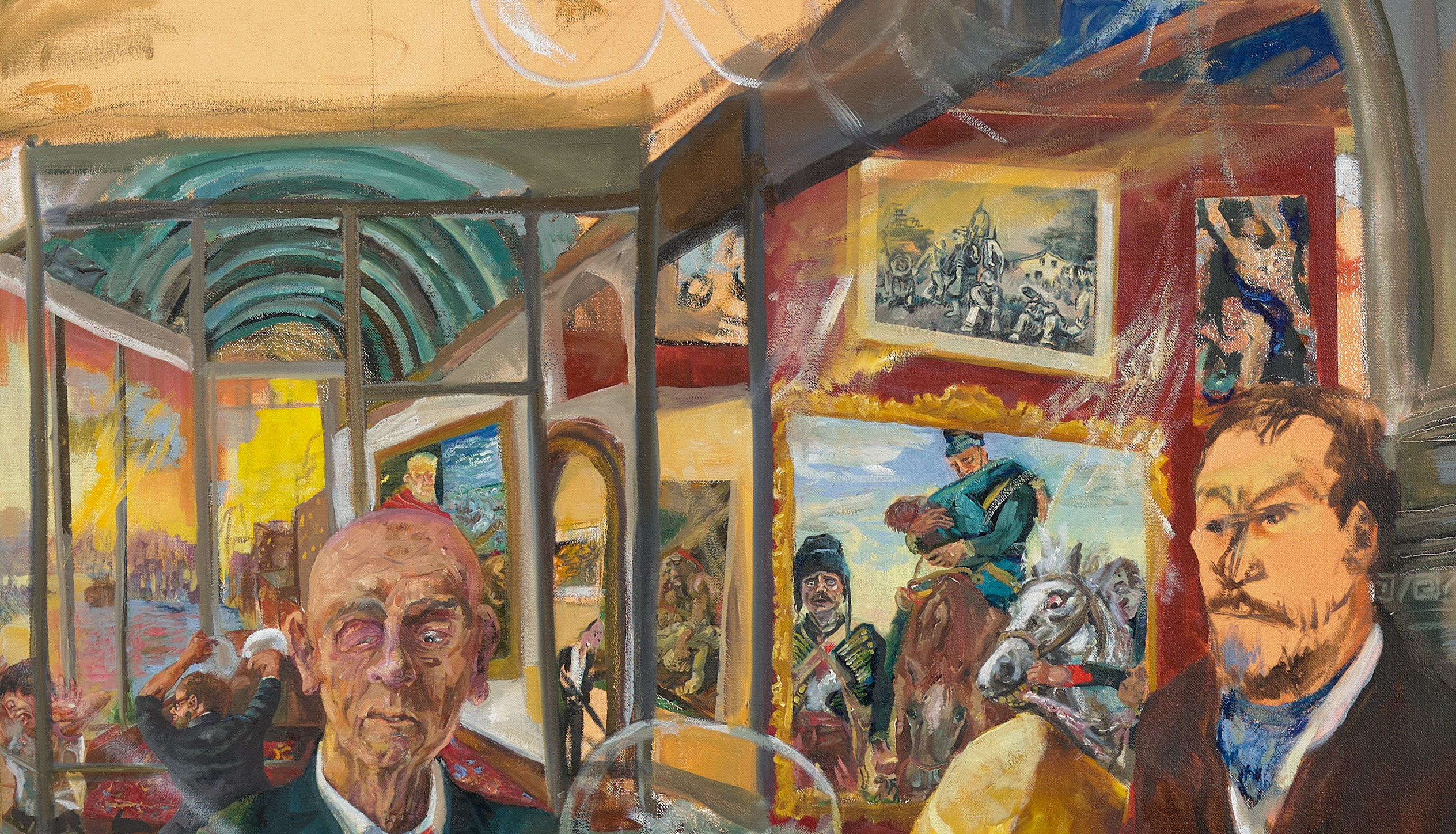

THE ART HISTORY ON THE WALLS Including these references to art history is one of the pleasures of having an art process whereby a painting unfolds over time and during so many thoughts. You get to make a claim or a hypothesis and then, through painting, connect all of the reasons around it that can make it come into being.

The man is surrounded by art historical events. There are these intentional moments that come from art history but are mainly details from bigger art historical pieces. One of them, the one with the horses, is this painting by Lady Butler. I look at her as a sort of patriotic war painter. But when you look closer you realise it is not patriotic; she’s painting the shell shock and the tragedy. Even between the soldiers who are smiling, there are those who are in absolute disbelief about what they’re seeing around them. This particular painting is the death of the bugle boy. Walking next to him is this very short man who has this look in his eye that is so haunted. Above him is George Bellows’ print of some of the atrocities that the Germans inflicted on Belgium during World War One where they massacred children in front of their parents. The soldiers are attacking the mothers of the children and the children are stuck on their bayonets.

Next to them is King Herod by Rubens. It’s on the cover of a Rubens book that I have in my studio. But I have taped over the faces of the babies as it’s too upsetting. And then to the left of the soldiers is the Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault zeroed in on the father weeping over his drowned son. To the left of the gunman peering behind the painting to see if there’s a hidden safe is a Tintoretto painting of a Venetian military man who protected Venice at sea against the Ottomans.

He won a battle at sea and saw a lot of death but died of a broken heart when a fire broke out in a great hall where a lot of beautiful art was kept. The idea of including him was centered on my thoughts about how devastating it is when our legacy is destroyed. All of these images are sort of like a mix tape of art. When I have a point I really do tend to end up grinding it!

THE MEN AROUND THE GUY ON THE PHONE

As frustrated as a I am about wealth disparity, and the brutality of what it takes to get to a certain level of wealth, I feel that while these people are deeply responsible for where they are, they are not fully responsible. They are ‘born into it’. Their values are a certain way. Their lives are exactly how they were told it would be. It’s complicated, but I think my empathy for the guy is in the way he’s depicted in jeans. He’s like how rich people always wear old jeans with bare feet, like they’re at the beach. Like they’re just a guy. He’s just a guy.

I end up feeling pity, and sorrow, and all those kinds of emotions for my characters. They’re humans right? And I dragged them into all of this. They came into being in this situation! But these are the people at the top. And they are going to be the people who survive. They’re a symbol of extinction. It’s a sort of a pointed anger. It’s really about the human on human brutality. Like luscious violence. It’s what happens when you have political opponents clashing on balconies! These things are brutal but they are the tactics that are used.

THE RIDDLES IN THE PAINTING

There are little kinds of symbols - like little signifiers or riddles that can add an element to the story. I put some wine bottles in there. One of the bottles of Austrian wine is in my mind a gift to the man from friends, thanking his family for ‘really being there’ when their son was killed in a car accident. There was this new Nazi party in Austria I read about, and Jorg Haider, one of the people in it, died in a car accident. And it’s just a reminder that the money on top goes to fund these things.

You can also see in the image this child’s ghost. In my mind one of the aspects of this is that presumably that child, if he were to live, would have been folded into this whole scene. In this core state I’m assuming the child hasn’t moved much beyond, so the child is filled with terrible rage at what’s happened and has this longing to go to the other side. So it ends up as being an angry or a terrified ghost that ends up clinging to its mother. It becomes a stand in for innocence. That symbol on the side of the boy’s toy truck (behind the man who is doing the peace sign) is one of the 72 names for God.

THE ICE BUCKET There’s another painter who’s coming up right now called Larry Madrigal. He’s out of Arizona and he came to my studio and was hanging out. I said you’re really good at doing metallic things so can you do the ice bucket? There are moments where I hit the wall in my ability to do things. I couldn’t make it and I kept on scratching it away. So he painted the ice bucket. I love it when there’s a chance to get someone else’s hand into my painting. You’re not really supposed to say that there are other hands that go into your paintings - even if it’s past a certain scale. I think the rejection of that is important. The discomfort around it is capitalist bullshit. It doesn’t make sense other than for the market.

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer received a BFA from Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York in 2007. Recent solo exhibitions include But the Clouds Never Hung So Low, Max Hetzler Gallery, Germany (2020), The Chiefest of Ten Thousand at Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles (2018); Wild and Blue at Marlborough Contemporary, New York (2017), and (mostly) works on paper at Artist Curated Projects, Los Angeles (2015).

Group exhibitions include This is America, Kunstahal Kade, Amersfoort, (2020), All Them Witches at Deitch Projects, Los Angeles (2020); Made in L.A. at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2018); TEN at Artist Curated Projects, Los Angeles (2018); The Whitney Biennial at the Whitney Museum, New York (2017) and Tomorrow Never Happens, The Samek Art Museum at Bucknell University, PA (2016). Dupuy-Spencer lives and works in Los Angeles. Find out more and register your interest in this edition here. Read another interview with Celeste Dupuy-Spencer here .