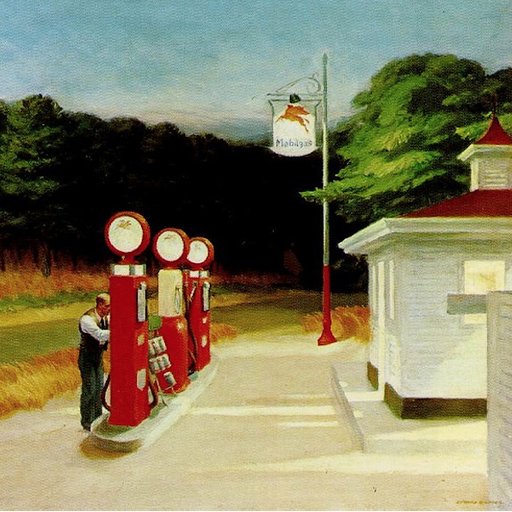

German visual artist Thomas Bayrle somewhat predicted the future—his early work utilized photocopy machines and other tools to create analog visualizations of what we know today to be digital culture. Through repetitive, textile-like patterns, Bayrle's art has a woven feel to it—which makes sense considering he began his career as a weaver. Coming out of Germany in the '60s, amidst rising capitalist/communist tension, much of Bayrle’s early art juxtaposes these conflicting ideologies. Spanning over five decades (Bayrle is now 80 years old), his work investigates notions of mass production and consumerism, and it’s larger relationship to global politics and culture.

Thomas Bayrle, Mao, 1966. Oil on wood construction and engine, 57 x 58 1/4 x 12 5/8 in (145 x 148 x 32 cm). Photo: Axel Schneider

Thomas Bayrle, Mao, 1966. Oil on wood construction and engine, 57 x 58 1/4 x 12 5/8 in (145 x 148 x 32 cm). Photo: Axel Schneider

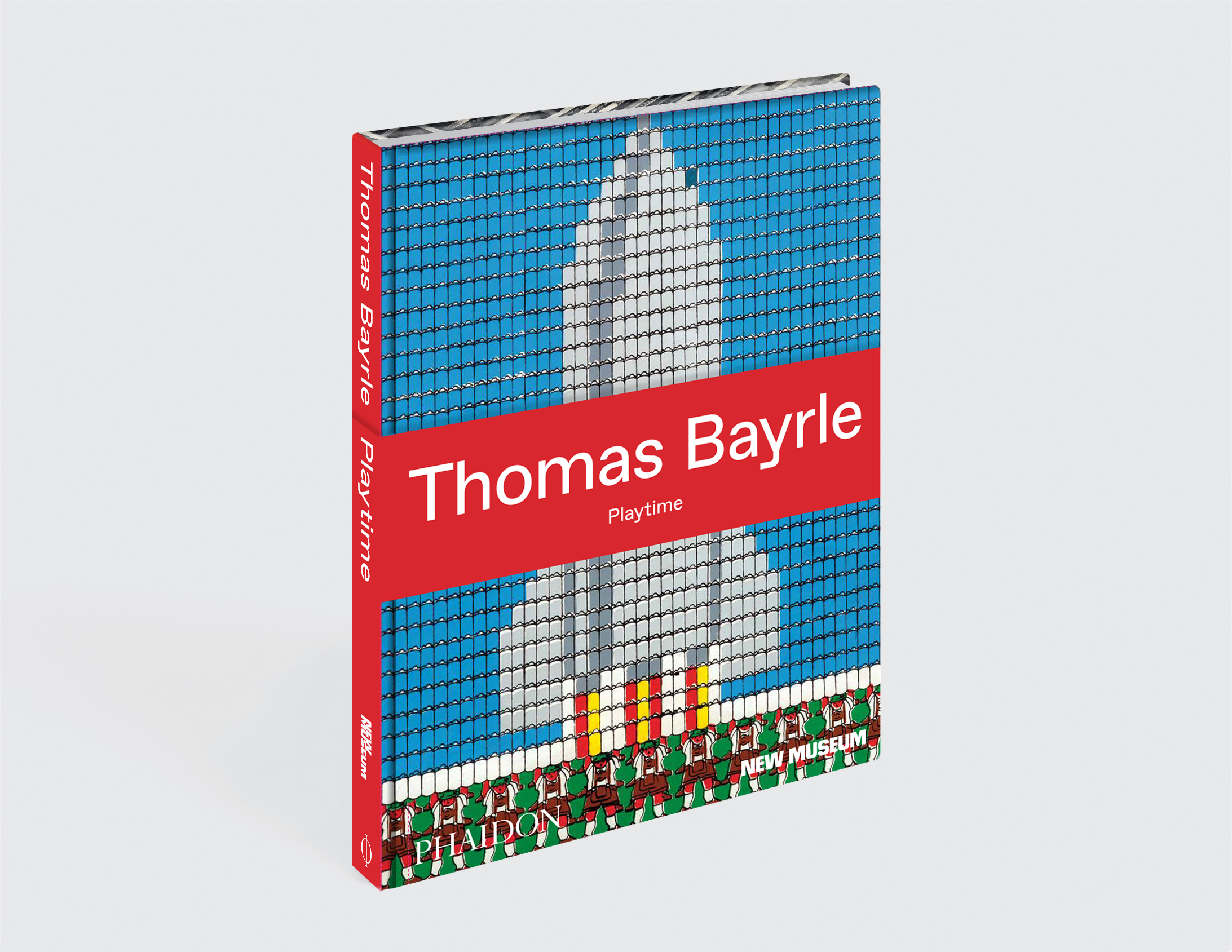

“Thomas Bayrle: Playtime”—now on view at the New Museum —is the first major retrospective of the artist’s work in New York. The show includes his most iconic works—from a wooden machine of hand-painted blocks, that when set in motion slowly morph Chinese Communist leader Chairman Mao’s face into a red star (part of his “painted machines” series) to tiny images that repeat in a tile-like manner to make up one giant picture (what Bayrle refers to as “superforms”). New Museum artistic director Massimiliano Gioni, who also curated the exhibit, interviewed Bayrle to discuss his influences, and what his work says about today’s technological age. The following was excerpted from Phaidon’s catalog of the exhibition.

Thomas Bayrle: Playtime

is available on Artspace for $79

Thomas Bayrle: Playtime

is available on Artspace for $79

My first question is the simplest and the most difficult: When would you say you decided you were going to become an artist?

Pretty late. I doubted myself because I was first an apprentice at a weaving company—which had a strong influence on my views about art and technology. After that I became a designer and a publisher, and while doing different jobs, I was always on the edge of being an artist. . . It took almost twenty years until I decided, “Now I am an artist.”

How did you meet Le Noci?

I had met Fontana several times before. And one day in Milan we visited him in his nice studio, and at one point he said, “Come on, let’s go to my gallerist. He should show you.” He was such a generous man. I really didn’t know why he did that for me; I find it hard to believe that an artist would do the same for a younger one today. So in 1966, I met Le Noci in his gallery in Milan. He wanted to show the machines, but I wanted to do something different. When he came to Frankfurt a year later, I really didn’t know where to take him—so I suggested we visit an American club. It was an absurd conglomerate of Bavarians in lederhosen, table telephones, and girls waiting for the GI customers. He was absolutely entranced by this place. I did my best to show him the culture of the street, what Frankfurt was really like. In 1968, we did the show in Milan with the printed matter works and the coats, paintings, wallpaper all over. Le Noci was a very generous man. This was actually the only time in my life that somebody bought the whole show. He said, “Let’s go to the bank—tell me how much the show is worth,” and he bought the whole show. It never happened to me again in my life.

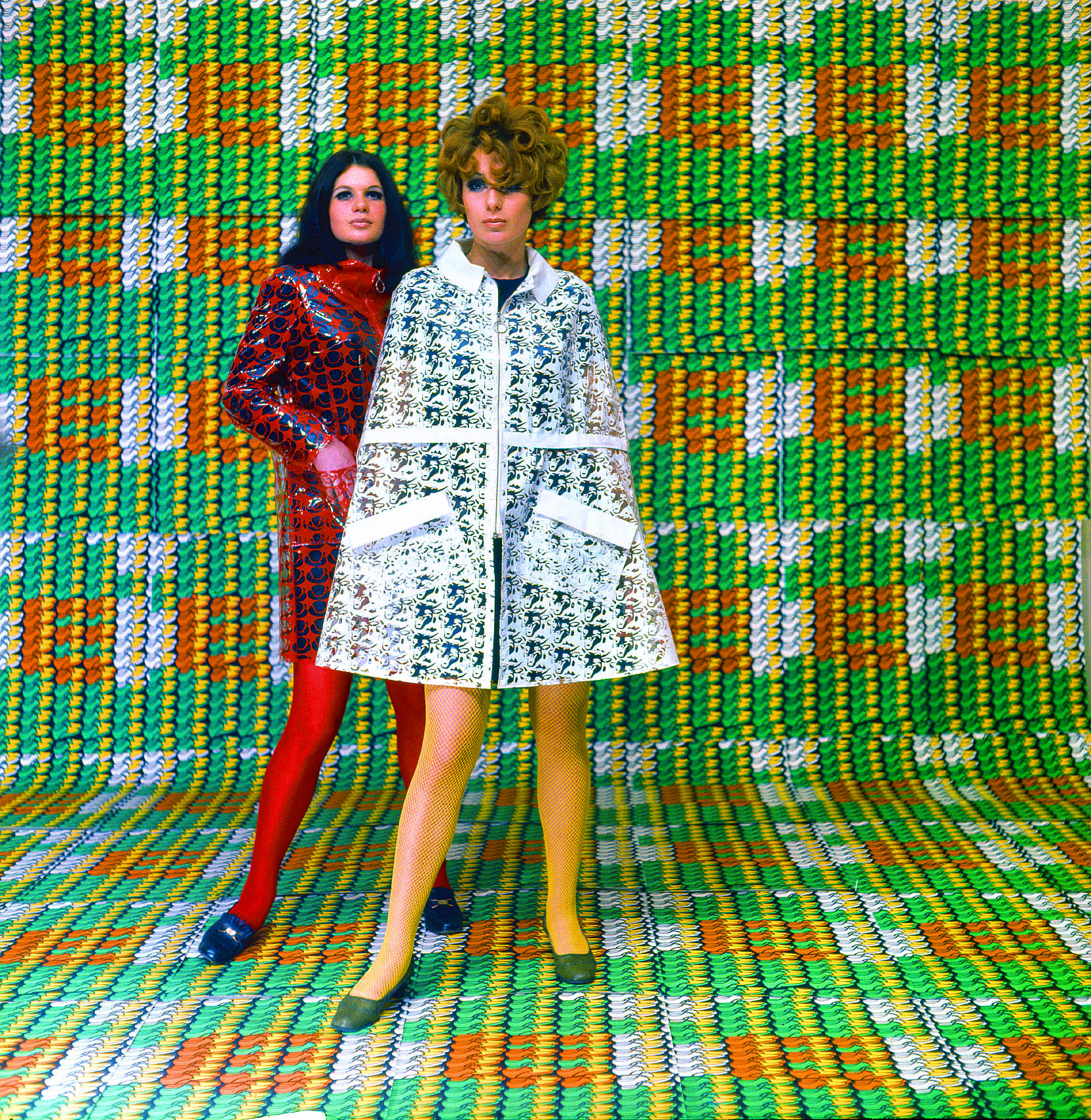

Models wearing coats designed by Lukowski + Ohanian with textile pattern by Thomas Bayrle, Galleria Apollinaire, Milan, 1967–68. Photo: Christian Roeder

Models wearing coats designed by Lukowski + Ohanian with textile pattern by Thomas Bayrle, Galleria Apollinaire, Milan, 1967–68. Photo: Christian Roeder

How did this idea of creating an entire environment for the exhibition develop? In the “Produzione Bayrle” show, you expanded your paintings and prints to the entire space, using carpets, wallpapers, and clothing. It was a kind of industrial painting stretched out onto any surface available.

Helmut Rywelski, who also showed the coats in Cologne in 1968, said they were like “moving prints.” For me, “Produzione Bayrle” and the work around this time were about approaching and confronting mass production in a technical, adequate way. Mass production appeared as a fairy tale, in which the potion in the cauldron was boiling and boiling and boiling and overflowing on the fireplace and onto the floor and sprawling up the walls and filling the globe. I wanted to make an environment that felt like this experience. I wanted the viewer to be surrounded by thousands of cows from the Vache Qui Rit cheese brand, or I wanted the viewer to be totally outnumbered by cups, logos, and shoes. I wanted my work to be produced in a proper manufacturing way, taking on the machinery with the same precision and the same excesses as the most advanced industry. I had to manufacture everything myself on the machines. So on Sundays, I would go to the printer and just produce and produce and produce. And the way in which the paintings and the wallpapers and the coats were presented was absolutely up to date—it was like what you would find in the most modern shops.

Would you say that the idea of creating an environment was also related to Fontana’s experiments with installation?

For me it really came from mass production itself. I don’t think many people had already realized what it meant that machines were working twenty-four hours a day, just producing toothpaste, toothpaste, toothpaste, toothpaste, day and night. Around this time, I visited a Ferrero chocolate factory, and it was incredible: millions of pieces of chocolate just churning out. Who was going to eat all this chocolate? It was absurd and somehow funny but also terrifying and sublime in its vastness. So I wanted to transform this very logic into my work: to mass produce my own work, without worrying about supply and demand. I wanted to express a sense of happiness and acceptance of this phenomenon and also to inject a fair amount of skepticism. This became a kind of procedure in my work: how to combine these two poles, a critical approach and the sense of excitement in the new possibilities that technology brings. I was never apocalyptic about change, but never just an optimist either. I was always on the edge, inhabiting the contradictions. I am not interested in moralism: the possibilities suggested by technology can be disastrous, but they are still possibilities, which can be embraced even in their most chaotic consequences.

“Thomas Bayrle: Playtime,” 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

“Thomas Bayrle: Playtime,” 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

How did this approach fit into your political beliefs and the political work you were doing?

I found myself literally living the contradictions of the time. During the day, I would work for Ferrero, Benckiser, Pierre Cardin, and McCann Erickson, the German factories and the American agencies, and at night I worked for the Marxists and the anarchists, the students, the Italian protest paper Lotta Continua , and the German extraparliamentary left. It was a bit Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde, but I thought it was a way to experience a more complete and complex identity.

Did you feel you were closer to one side or another, or that your artwork was about this contradiction?

The contradiction was what interested me. You have to understand that both sides were very dogmatic. In the 1960s, when I painted my Mao machine, first of all I had to get a picture of Mao, which wasn’t that easy; I found it in Milan in 1964. Germany at the time wasn’t even that interested in the rest of the world. And then around that time, I was curious about the Marxist-Leninist movement and new ways to define and transform the left. So I showed my Mao machines to some of members of the movement, and they told me, “Your painted machines are reactionary, because you paint Maoists with neckties!” It was really a very strange exchange. That’s why I made the print with the cowboys swinging lassos to compose the ML logo of the Marxist-Leninist movement: to me, at that point, opposite ideologies appeared very similar in their optical manifestations.

“Thomas Bayrle: Playtime,” 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

“Thomas Bayrle: Playtime,” 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

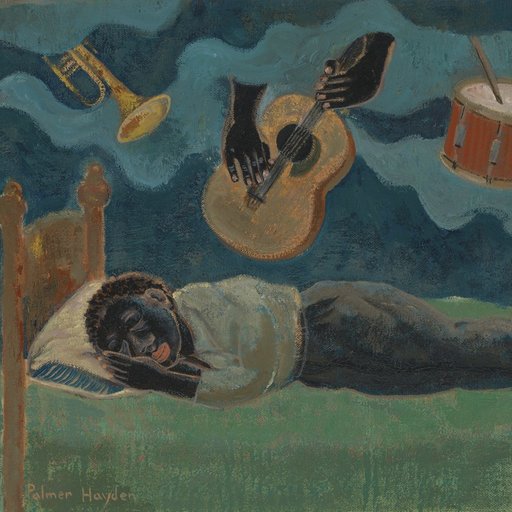

Sexual liberation was something you devoted a few works to, in particular your set of prints titled Feuer im Weizen [Fire in the Wheat].

Yes. After the war, sex was not at all a theme in German public discussions. It was approached quite conservatively and was not really part of the whole rhetoric of the economic miracle. This changed radically in the ’60s. All of a sudden, sex turned into a major force of social change. And it turned into big business. The story of Beate Uhse, a former World War II pilot who, after the war, started selling condoms and birth control with a mail order catalogue and went on to open the very first sex shop in the world, gives you an idea of the changes Germany went through.

How did your city landscape works develop?

It was a structural transformation of my work: I wanted to create a series of “average cities.” Technically, I decided to create these works with a set of modules and collages, by endlessly varying the same motifs. I wanted to work with modular constructions and bring these into a new system, a bit like minimal music: my intention was to create about ten or fifteen modules, which would be woven together, creating a potentially infinite set of procedures. I started with a number of isometric photographed toys, which were combined almost as in a puzzle. With a few elements and a series of endless variations, I could create immense cities.

I wanted my artworks to evolve and grow like cities and companies do within the capitalist system. Companies work with their financial tools, real estate conglomerates have their own systems, and I wanted to create my own tools. For me, my city landscapes had a lot to do with the way finance turns abstraction into physical spaces, how capitalism acts behind cities, how numbers become things. The cities paintings were also a form of coding; maybe that’s why today they look like ancient video-game landscapes. And for me, they were also about music and modulation, so in a sense they were very close to the texture of the fabric I had learned about as a weaver. I was weaving streets.

![Thomas Bayrle, Stadt [City], 1977. Photo-collage on wood, 66 7/8 x 53 1/8 in (170 x 135 cm](https://d5wt70d4gnm1t.cloudfront.net/media/a-s/articles/2783-332356451869/superforms-and-praying-machines-massimiliano-gioni-interviews-thomas-bayrle-ORIG.jpg) Thomas Bayrle, Stadt [City], 1977. Photo-collage on wood, 66 7/8 x 53 1/8 in (170 x 135 cm). Photo: Wolfgang Günzel

Thomas Bayrle, Stadt [City], 1977. Photo-collage on wood, 66 7/8 x 53 1/8 in (170 x 135 cm). Photo: Wolfgang Günzel

Did you have specific architects in mind when you started working on the city landscapes? Or specific cities?

Not really, it was more a generic landscape. I like the ugliness of cities. I’m even attracted by the boredom of certain cities. The famous architects, they are not the only ones who leave a major mark on cities. I was more interested in the structure, the superstructure that brings together billions of people and housing and businesses and traffic, mixing into each other like a huge, dense network of civilization. For example, I was quite interested in a city like Chicago, which in those days was still very ugly. And then I started looking at Asian cities; I was in Asia a lot, and I liked the monotone quality of Tokyo. I wanted to express the possibility of a small space of privacy in an impossible, huge slum.

Is that the principle behind what you called “superforms”?

The idea of the superform had to do with a sculptural quality. If you fill a piece of canvas with the same elements, say apples or pears, and you group them to create the shape of a larger apple or pear, you create a sculptural form out of the flatness of the individual elements. All of a sudden, through the repetition of singular forms, you obtain the illusion of a three-dimensional shape. For me, a superform is the addition of elements to a flat surface until it turns into depth. One of the first superforms was the Volkswagen piece, which was made with thousands and thousands of images of small cars. At this point I was interested in the idea of overproduction and inflation. Now we have moved toward customization—we have computers and we make things to order—but when I was making these works, there were acres and acres covered in cars, millions of unsold cars. On the other hand, when I was making the first superforms, like the portrait of my mother made of telephones, I still didn’t have a phone at home—that’s to give you an idea of how much the impact of technology had changed over the course of my life.

![Thomas Bayrle, Flugzeug [Airplane], 1982–83. Photo-collage on paper, 315 x 527 1/2 in (800](https://d5wt70d4gnm1t.cloudfront.net/media/a-s/articles/2783-332365106453/superforms-and-praying-machines-massimiliano-gioni-interviews-thomas-bayrle-ORIG.jpg) Thomas Bayrle, Flugzeug [Airplane], 1982–83. Photo-collage on paper, 315 x 527 1/2 in (800 x 1340 cm). Installation view: “Von hier aus. Zwei Monate neue deutsche Kunst in Düsseldorf” [From Here: Two Months of New German Art in Düsseldorf], Messegelände Halle 13, Düsseldorf, 1984. Photo: Gerald Domenig

Thomas Bayrle, Flugzeug [Airplane], 1982–83. Photo-collage on paper, 315 x 527 1/2 in (800 x 1340 cm). Installation view: “Von hier aus. Zwei Monate neue deutsche Kunst in Düsseldorf” [From Here: Two Months of New German Art in Düsseldorf], Messegelände Halle 13, Düsseldorf, 1984. Photo: Gerald Domenig

The Volkswagen piece was shown along with the airplane in the exhibition “Von hier aus. Zwei Monate neue deutsche Kunst in Düsseldorf” [From Here: Two Months of New German Art in Düsseldorf], which Kasper König organized in Düsseldorf in 1984. The airplane in particular was the largest piece you had ever created. How did this project develop?

I started with a very small airplane. In 1980, Lufthansa approached me and asked me if I could design an airplane using my superform style. They wanted to have the image of a plane made as a pattern to be used on their first-class airplane. I made that and then I said to myself, “You’ve got your airplane, but now I’ll make my airplane.” So I took the design I had created for commercial purposes and enlarged it. The process is quite vertiginous because in order to enlarge the piece, you actually have to make other, smaller planes. In a sense, it can only get bigger if at the same time it gets smaller, more detailed. The plane I had made for Lufthansa already contained 2,000 small images of the same plane. But I wanted to get to a scale that would be comparable to what felt like the beginning of a whole different paradigm. It was the 1980s, when air transportation had truly become global: airports were becoming cities and, while the whole industry was much smaller than today, it suddenly became very clear that the airplane would change the whole world, like the telephone or television had, or the iPhone would. Like the factories in the 1960s, the airplane had become a source of horror and beauty, a super-horror and a super-beauty. So I made this airplane that is composed of more than one million little airplanes. Each airplane is different from the others; it was all made by hand, by distorting each piece of latex rubber and photographing it, printing it, and applying it as a collage. Your mind can read and understand differences, and realizes that this airplane is made of all these different parts, each unique. I believe in total individualism, even in the largest mass. Even in billions, everything is singular and unique. Every cell, every atom, they are singular. I think that’s the richness of art, to define this singularity in the mass.

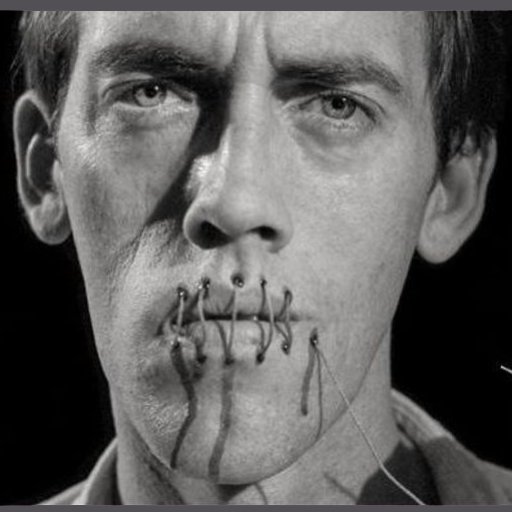

There is something almost spiritual, even messianic, in this approach. How did you come to the religious references you have used in many of your pieces?

I was not raised in a very religious family but, maybe because my father was also a painter, I was interested in icons from an early age. In that type of religious painting, forms are given: the size, the colors, the handling of the paint—they are all decided, strictly regulated by tradition. It’s like a machine, but a machine made by monks. I liked this idea of repetition; I liked that monks painted by following rigid rules, but I also liked that even within such a strict structure there was always space for diversity. I like the closeness of individual differences. Trying to be the same, but always failing. Or trying to be different and realizing you are just like all the others.

![Thomas Bayrle, Madonna d’oro [Golden Madonna], 1988. Photocopy collage and gold leaf on wo](https://d5wt70d4gnm1t.cloudfront.net/media/a-s/articles/2783-332386525699/superforms-and-praying-machines-massimiliano-gioni-interviews-thomas-bayrle-ORIG.jpg) Thomas Bayrle, Madonna d’oro [Golden Madonna], 1988. Photocopy collage and gold leaf on wood, 78 x 57 1/2 in (198 x 146 cm). Photo: Wolfgang Günzel

Thomas Bayrle, Madonna d’oro [Golden Madonna], 1988. Photocopy collage and gold leaf on wood, 78 x 57 1/2 in (198 x 146 cm). Photo: Wolfgang Günzel

How did the idea of the praying machines develop?

First of all, there was my experience in the weaving factory, where the sound, after a while, just became a drone, a meditative humming. And in Asia, I had seen the wind instruments that Buddhists use for their prayers: those are meditation machines, in a sense. Technical helpers are always inspiring to me. Engines work because of millions of small explosions, which add up and keep the pistons moving. To me it seems like the same logic as a rosary, where you have hundreds of prayers and Hail Marys that build upon each other in a bigger explosion of faith. . . . I was always puzzled by the economy behind confessions and prayers: I like how ten prayers can pay for a certain amount of forgiveness, and twenty more take care of the extra guilt. Praying is work, it’s labor. The sheer amount of time one puts into praying could be measured in work hours. The idea of the engines has to do with this idea of labor and production as both burden and illumination.

Do you think our souls will be saved by technology?

I read an article in which Pope John Paul II was asked when he found time to pray. He said he prayed all the time. I think I could relate to that: I feel that machines can help us when they extend our bodies and work like our bodies. In the end, it’s always a matter of micro-differences between individuals; maybe that’s where salvation is, in the difference between one and zero, off and on, same and different. All the world is built on power and energy generated from small bits and pieces.