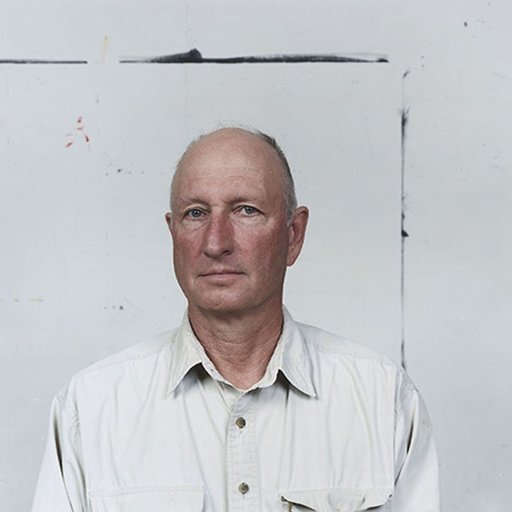

There's one thing that the National Gallery, the Royal Academy and the National Portrait Gallery (three of the UK's most prominent institutions) have never done before: collaborate to present the work of a single artist across all three museums. That is, until they did, beginning this March, with artist Tacita Dean . Yeah.

In each show, the British artist investigates one of three themes: still life, portraits, and landscapes. And while she's been known to toggle between a range of media (drawing, installation, audio, performance), she's most known for using film—antiquated, discontinued, on-a-spool film. This is just one of the good reasons why Dean may have started out as a member of the Young British Artists (along with artists like Damien Hirst , Gary Hume , and Liam Gillick ) but has since proven that she is in fact very much her own thing—much more ambient, meditative, and nostalgic than her contemporaries. Chasing stories and digging up history is her true passion, and her films tell tales that blur the lines between historical fact and fictional narrative.

Here we revisit a conversation excerpted from Phaidon's Speaking of Art: Four Decades of Art in Conversation , in which art historian Jean Wainwright speaks with Dean about her formative multi-media series inspired by the true story of one man's tragic death while traversing the Atlantic Ocean, titled Disappearance at Sea (1995-97). Dean describes her compulsion to document forgotten fragments of history; the ways in which chance and coincidence influence our daily experiences; and the relationship between fact and fabrication. Read up on this influential artist, and if you're in London, be sure not to miss her museum take-over.

---

Tacita, could we begin by talking about one of your latest works, Disappearance at Sea ?

The piece is a fourteen-minute film on 16-mm. It's filmed in CinemaScope, which means that the format of the frame is twice as long as a normal projected frame, so it has proportions of approximately one to two and a half. I was commissioned to make it for the Berwick Ramparts Project in 1996, specifically for the lighthouse at the end of the quay in Berwick-upon-Tweed. It was a fixed-light lighthouse, so it didn't have a rotating bulb, and I was to project the film on the second floor, which was a dark enclosed space. The projection distance was only six feet––it was a very, very tiny lighthouse. That is why I went for the extended frame, for the CinemaScope, because I wanted the sense of light traveling through the frame.

The genesis behind the actual work was my investigations into Donald Crowhurst, who was the lone yachtsman who disappeared at sea in 1969. History has always attracted me, and I'm fascinated by fact and fiction. Crowhurst set off as an amateur sailor in 1968 as part of The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race. In 1967, Sir Francis Chicester had become the first man to succeed in sailing solo round the world, although he did have a stopover in Australia. So as a response to that, The Sunday Times issued a challenge for someone to do it without stopping. About eight people went in for it. Crowhurst, who was an amateur sailor in Teignmouth, Devon, and a married man with four children and a failing business, very naively took up the challenge and set off on October 31––the last possible date. This bright but fairly mediocre person set off to navigate the "unknown."

When he got halfway around the Atlantic, he realized that his boat wouldn't make it. So instead of giving up (this is where the story takes on this very curious quality), he decided to fake his journey. He cut off his radio contact, but the world started to fake his journey for him. He had a press agent in Teigenmouth who was saying, "He's past the Falkland Islands." Meanwhile, Crowhurst had entered into a psychological state that was, I think, mirrored by the state of the sea, which is where my interest in him comes from. All sailors have to have a chronometer to plot where they are in the world in relation to time in Greenwich and time on board the ship. Crowhurst committed a cardinal sin in sailing––he let his chronometer stop––and he lost all sense, not only of time, but of where he was in the mass of the ocean. He then suffered from what is known as "time madness," because he had no props to hang anything on. Five or six months later, his imagined journey caught up with where he was in the Atlantic. He re-opened radio contact, and he was winning the race. I think at about this point the became obsessed with his deceit, his great lie, in a huge, existential way. It's very sad, because he jumped overboard with his chronometer, and they only found his empty boat.

My fascination with him is to do with human frailty versus the sea and with time. So when I had the opportunity to make a work in Berwick-upon-Tweed, I chose the lighthouse, because lighthouses are built to a human scale, and they are beacons of safety versus the unknown of the ocean. I filmed Disappearance at Sea (which was the first one made in CinemaScope) at Saint Abb's Head in Berwickshire in Scotland. The decision to make it in CinemaScope was fortuitous in terms of the pace of the film. Basically, it shows the moment when the daylight fades, the light comes on and the lighthouse becomes functional. And so you go from daylight to night. The last show is when, for the first time, you look out to sea. Up until that point you're looking at the lenses and the refraction and the actual turning of the bulbs, and then the light on the cliffs.

First of all you've got the machinery sounds in Disappearance at Sea , and then this extraordinary sound of seabirds in Magnetic .

Logistically, I taped wild sound when it was there. Saint Abb's Head is actually a nature reserve so that's why there are so many seabirds. Magnetic is to do with transcribing a sound through a passage of time into a physical distance, a physical length––a piece of magnetic strip related to the length of each call of a seabird that was native to the shores of Great Britain. So, for example, a cormorant would be one length, and a gull another. It's a way of breaking down sound and making it into a physical thing. You actually don't hear it––you just see it. And of course it relates to the seabirds at the end of Disappearance at Sea .

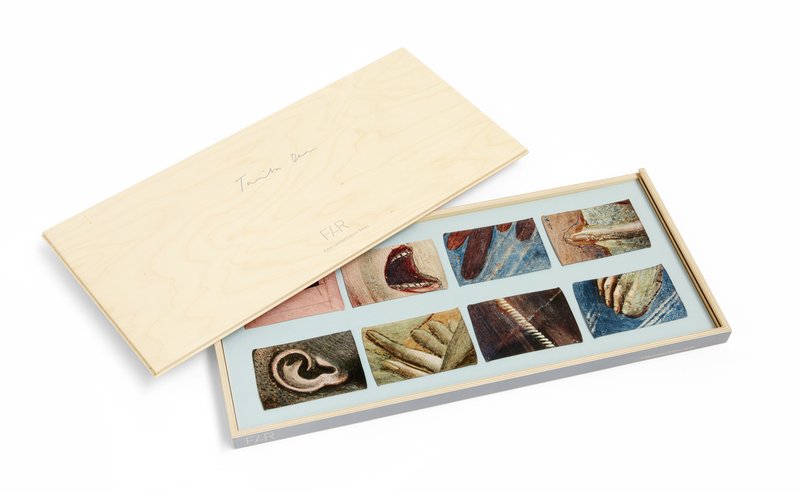

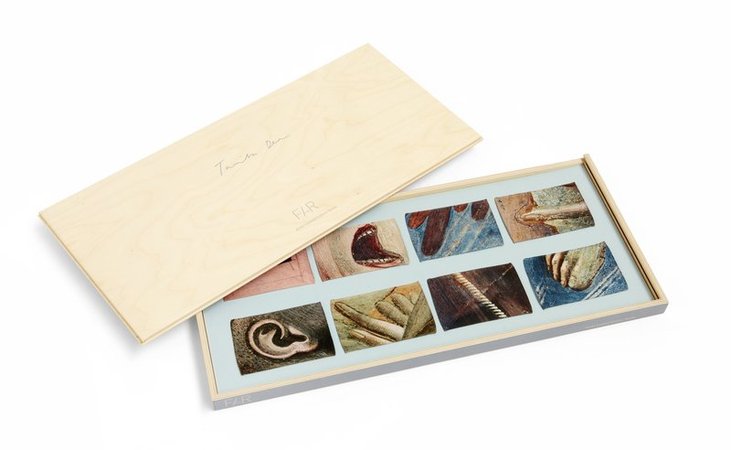

Tacita Dean, Pocket Series, 2016, Available for purchase on Artspace $529

Tacita Dean, Pocket Series, 2016, Available for purchase on Artspace $529

The other thing I loved about the piece was when you move away from the actual filming inside the light to the enormous expanse of the sea and the light trained on it with nothing there.

Well, the thing about the last shot of Disappearance at Sea is the void rather than the light, the extent of the blackness, until the light picks up a tiny bit of the sea, just a flicker. It always reminds me of early film when you just see a seagull and it's fake. It's not the light house making that light––it's a 200 kilowatt bulb that I took up to Berwick-upon-Tweed. We moved it at the same pace along the water. Lighthouses don't pick up the surface of the sea, but I wanted to have a sense of "out there." That last sequence was staged, very fortuitously! I had no idea it would come out as it did. It has a very, very otherworldly quality.

It does, and it works beautifully.

Disappearance at Sea is connected in this curious way to a film I made in this alchemical palace in Bourges, France, of a statue that was totally out of context, called Tristan and Isolde , which triggered off an interest in their story. When I was reading it, it talked about Tristan doing this voyage de guérison , or voyage of healing. Tristan surrendered himself to the forces of the sea, put himself in a boat with no oars or sails or rudder, and allowed the wave, the wind and the current to guide him to a "healing place," which is a metaphor for death. In his case, he landed in Ireland, where Isolde managed to cure him of the poison he had swallowed. I was interested in that idea of surrender, because there's something about it in Crowhurst's tale.

I found another story, which I rather liked, about a Portuguese admiral who went blind and was sailing in the southern Atlantic when he came across an island by mistake and he called it Tristan da Cunha––it's about as far as he got on his journey south. I made a little book of writing that went parallel to the show, with tangential thoughts. Disappearance at Sea is like the narrative that was left off. It was filmed at Longstone Lighthouse in Northumberland, England, which is quite important, because there's a national thing going on as well––Scotland, England and Berwick in between, which is a contested land between the two countries. We put the camera where the bulb would be, and it turns, so you see what the light would see, all the way round the lighthouse, the sea and the land. I went to Falmouth School of Art, and I do love the sea. I have a passion for it.

In your recent show at Frith Street Gallery you included Delft Hydraulics , which is different again.

Well, that one I made for my show at De Voorst, and I was immediately attracted to the idea of this marine laboratory in Delft. I went on a guided tour there and I was interested in these huge wave machines, which are an anachronism, like film itself. They don't use them anymore––they use computers––so they hardly ever turn them on.

What did they use them for originally?

They'd pile up marbles at one end, stuck together with this kind of weak glue, and then they'd send waves down at different rates to learn about the deterioration of the surfaces. I don't know how they gauge any information from them, because they looked quite useless to me. All three works in the Frith Street Gallery show are very informal sculptural works, which is a departure for me. I used to work so much more with narrative, but I've left the stories off in these three films because the visuals were so strong. With Delft Hydraulics and Disappearance at Sea, there was very much a sense of trying to control the sea, of trying to test it. That was the conceptual thing behind it, but in terms of what it turned out to be, it was much more to do with surface, film and rhythm.

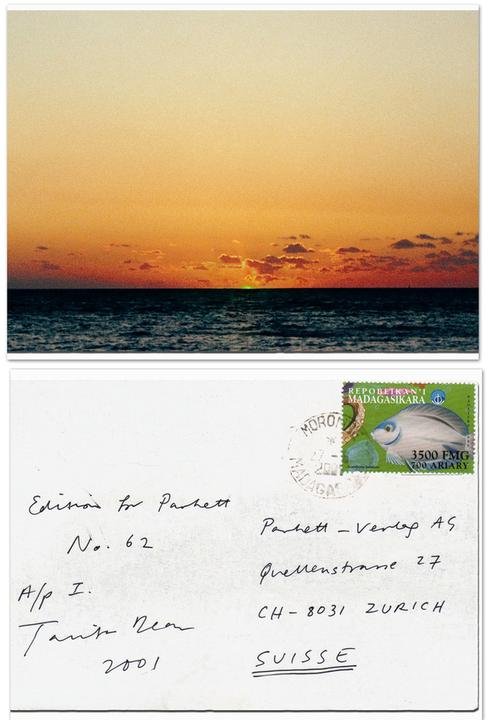

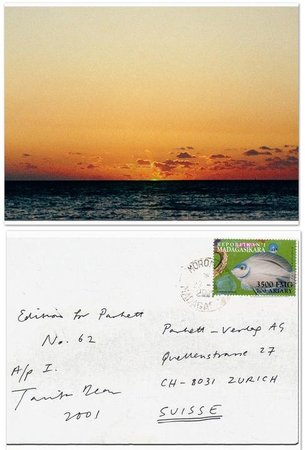

Tacita Dean, The Green Ray, 2001, Available for purchase on Artspace $800

Tacita Dean, The Green Ray, 2001, Available for purchase on Artspace $800

And another work that links to these, in terms of water, is your search for the Spiral Jetty .

This summer I went to the Sundance Institute, Robert Redford's personal film school, which was amazing. While I was there, it occurred to me that Utah and Salt Lake City was where Robert Smithson did his Spiral Jetty . And it was very strange to finish this Hollywood screenwriting lab, and the next day to go and find an old icon. I went with a friend from the Director's Lab, and the Utah Arts Council faxed me the directions. When I was looking for Spiral Jetty , I had no intention of making a piece of work. It was an incredibly long journey that was was coded with instructions like, "This is cattle guard I. There is a fence but no gate." And gradually you weave your way further and further away from society, and it gets more exciting. Greg, who I was with, had no idea what the Spiral Jetty was, but he got really into the spirit of it.

When we got to the point where it was supposed to be, we didn't know if we were looking at it or not. There was this jetty, and I didn't know if it was the Spiral Jetty or not. I still don't know. It was covered in salt-covered weed, and it was incredibly beautiful. I brought some of it back. I went home via New York, and I bought this book on Smithson, and there were photos in it of this stuff, and I got terribly excited about the Spiral Jetty . I decided I really wanted to make it into a sound piece. I asked Greg, who lives in Los Angeles, to try and relate the journey into a DAT machine, and I tried to do the same here. So it became a thing about memory.

Also, ironically, it related to screenwriting, because, in the end, I had to edit those two bits of memory together, to try and remake the journey. I also had to go and tape the sound of the cattle guards and driving and all sorts of sound effects, which I edited together, so it's actually a complete fabrication. People don't realize this. There's a point when my fake bit reaches the real bit, which is actually, it only occurred to me the other day, what happens to Crowhurst. You get this sense of searching for something, and then, when you get there, it's like "was that it?" In a very satisfying way, the whole show did have these incredible connections going the whole way through it, some invited, some not. I rely on chance connections quite a lot, actually, and chance happenings, but it was particularly nice, with that show, because it all related quite well.

You mention fact and fiction, and of course that recalls your installation for Tate's "Art Now" series, Foley Artist.

A foley artist is somebody who makes human sounds for cinema that can't be captured on film. When Tate asked me if I had an idea for "Art Now," I said I really wanted to make a fake soundtrack and that I was simultaneously very interested in foley artists and the whole idea of the fiction of sound you year. As the work progressed, I found out that ninety percent of cinema sound is fiction, which is such a glorious license. At Shepperton Studios, I actually faked a cinema––although it was only seven and a half minutes––using two foley artists.

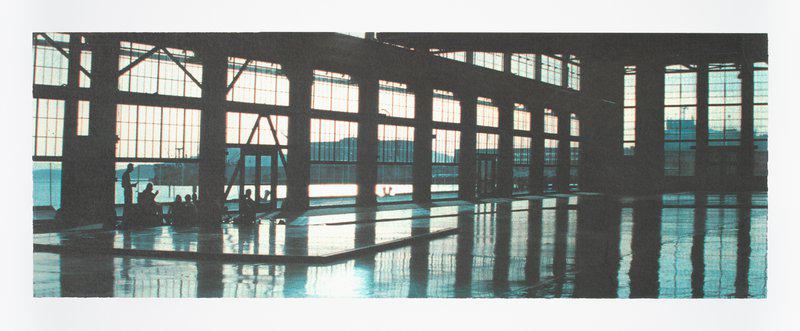

Tacita Dean, Craneway Event: Day One, 2010, Available for purchase on Artspace $5,289

Tacita Dean, Craneway Event: Day One, 2010, Available for purchase on Artspace $5,289

I loved the way that I had to turn around when I was reading the cues, and then I had to turn my back on one or the other to see the work.

That was very, very specific. In fact, it was essential to that piece, because it was very important that people actually stopped to listen to the whole sound. And then there was a fourteen-foot-long dubbing chart, where everything was documented and you could work out where you were. All the camera sound was stereo, but there were actually eight tracks, so it was four times more than you'd normally hear, and therefore it was very sculptural. We had three atmosphere tracks at the top, which were things like airplanes going overhead, but also the sounds of people whispering and chatting, of clapping and applause. And then, at the bottom, I had the "footstep" tracks, which came from three different speakers. So there were three speakers at the bottom, and then there were two that were human height. I used the room sculpturally. When there was the chase on the beach, the footsteps actually ran around the room, because I moved the sound from the speaker in the corner to the speaker on the other side. Then we had things like cars going past you in the room, so it was actually, if you closed your eyes, a complete lie. What was great was that if you closed your eyes it might sound as though it was pouring with rain or there was a thunderstorm, but then when you looked at the screen, you saw a totally dry studio and Beryl with a bit of wet newspaper. It had a lot of charm in it.

Also you had a huge old recording machine. Where did you get that?

It was a 16 mm Sondor magnetic track playback machine. It's a rather beautiful dinosaur of a machine––still used, but very rarely. I use them for my films, but in this case its use was related to the passage of time, because I wanted to give the illusion that it was an analog piece, when in fact it was the most state-of-the-art digital installation. Cinema gets int eh way of a lot of things. Jack Foley, the original foley artist, had all the tricks of the trade. These have been handed down for years in the cinema and have become what we hear. If you actually hear straight recordings of the sound of footsteps, it's nothing like cinema "footsteps." Cinema soundtracks have usurped what we consider to be sound. It's incredible. Foley artists actually dictate what we hear.

RELATED ARTICLES

Accidental Listeners: Tacita Dean Explains Anri Sala

The YBAs Still Rule at London's Contemporary Auctions