What do pizza, dolphins, and the incarcerated rapper Max B all have in common? The Internet inexplicably loves them, and they appear on tapestries designed by the emerging New York artist Azikiwe Mohammed. Mining the substrata of the Twitter- and Tumblrverse for inspiration from what he calls “the hive mind,” Mohammed eschews questions of originality and authorship in favor of translating the growing lexicon of Internet memes into the physical realm.

In addition to his tapestries, the Tribeca-born artist makes paintings of burgers after Botticelli’s Venus, commemorative plates featuring the infamous Atlanta rapper Gucci Mane, and surprisingly sensitive photographs based on the work of Stephen Shore, one of his photography teachers at Bard. Mohammed (much like the Internet itself) loves recurring imagery, especially when focused around what might be called “bad” food (think fast-food cheeseburgers, chicken fingers, and dollar slices). In keeping with this more gastronomic side of his work, Artspace’s Dylan Kerr met with the artist at Greenwich Village’s $1 Pizza, $2 Beer for a slice and a chat about his novel approach to image-making.

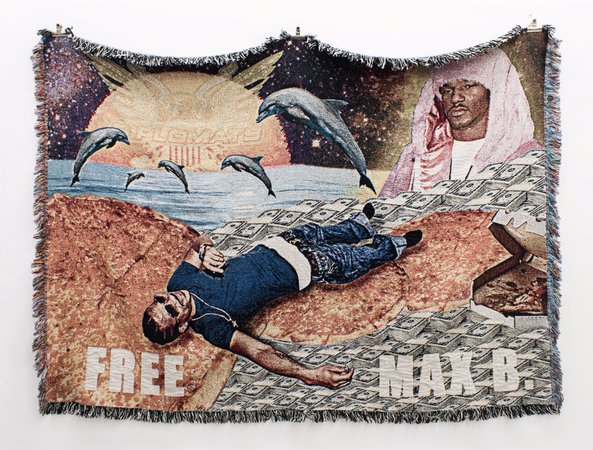

Free Max B, 2014

Free Max B, 2014

A visual magpie, Mohammed makes no secret of his fascination with the user-generated nature of the Internet’s favorite images and hashtags, which he sees as a kind of natural language arising out of the interactions between disparate individuals in the process of creating communities online. “Tumblr and Instagram are still reasonably openish fields, where the user leads,” he says. “What you see as you scroll through are certain touchstones, because people use these platforms as safe spaces where you’re able to express yourself as freely as you want—sometimes for good, sometimes not—and also as a space to mark one’s presence, to say, ‘I am here. This is proof of me existing at this time. I belong to a larger group of people. I am not alone.’ To do that, you need to have some kind of language chopped out.”

His favorite example of this process in action IRL is the California-based chain In-n-Out Burger, which allows customers to order items off a secret menu if (and only if) they know what to ask for. Like memes, this is a language of access and belonging rather than simple communication. Using these digital signifiers in the fine-art context is a no-brainer for Mohammed: “I don’t really feel like the Internet exists anymore. It’s so much a physical part of where we are that it doesn’t feel like a separate entity.”

Free B.G., 2014

Free B.G., 2014

This idea may seem to fit snugly within the nascent Post-Internet paradigm, but Mohammed sees himself as a digital native speaking the local tongue, as opposed to an e-anthropologist gathering field recordings. He’s not interested in whether or not he fits into any so-called movement—there’s already a context for his work beyond the confines of the art world.

In his Internet tapestries, for example, modern hip-hop heroes like BG, Max B, and Lil Boosie (whose incarcerations have spawned now-ubiquitous #FreeMaxB/#FreeBG/#FreeBoosie hashtag campaigns despite their music remaining relatively unknown) are surrounded by heraldic symbols of the Web like dolphins and galaxies, a contemporary take on the medieval medium woven using an online service that renders digital images as blankets. “I used the Internet for the Internet tapestries, because you’ve got to keep it in the same conversation,” says Mohammed. “They got picked by the Internet, they’re surrounded with things from the Internet, and if they’re made by the Internet, then they are a fully realized item.”

Gucci Mane Commemorative Plates, 2015

Gucci Mane Commemorative Plates, 2015

The same rationale follows through in his Gucci Mane commemorative plates. Mohammed chose the commemorative plate as his medium for what he calls their “celebratory” qualities; as one of the most influential hip-hop artists in recent years, Gucci Mane has achieved widespread adulation (as well as his casting in a pitch-perfect role in Harmony Korine’s 2012 film Spring Breakers) despite spending much of the past decade in and out of prison on various charges ranging from aggravated assault with a deadly weapon to simple moving violations.

In his effort to celebrate the prolific MC, Mohammed made sure to source his materials from an appropriate place, in this case a professional commemorative plate maker in the South. Again, speaking the right language is a central concern: “If I make an item that looks like the original, historical item, very rarely does one ask, ‘Who made it?’ but rather, ‘Where does it come from?’ I like the question ‘where?’ as opposed to ‘who?’ because ‘where’ is a location that holds many people. It immediately takes the emphasis away from the single author and puts it back on the community—that’s if you nail it. A lot of the people who are interested in the plates are antique dealers. It makes sense—they didn’t understand who the person was. If you follow the rules of the item, the people who have chosen to affiliate with said item are going to be the first responders, because they speak the language already.”

Riversmith's, Lubbock, TX, 2012

Riversmith's, Lubbock, TX, 2012

Concurrently with his meme-mining, Mohammed has been occupied for the past five years on an ongoing photo-road-trip, retracing and reshooting the steps of Stephen Shore’s famous Uncommon Places. This is more than mere appropriation; Mohammed’s Frequent Abberations documents all aspects of his journey, including his cheap eats along the way. As with his other work, context is king: “I shoot whatever the food is that’s most available wherever I am. As a photographer, one of my main jobs is to act as a mirror of whatever is happening. If you can use a machine that can get pretty close to reality, it’s to point the mirror at something. The pictures that surround those food items—because those were taken out of their contexts—are of the people who live in those places, and the locations themselves.” For Mohammed, these dishes function much like his favorite memes: markers of people in time and place, subtle signs of belonging.