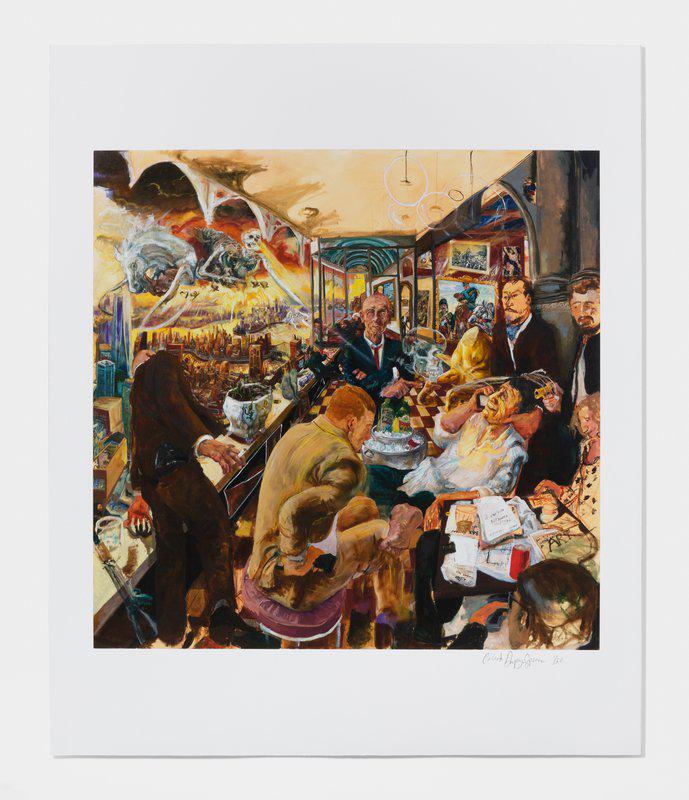

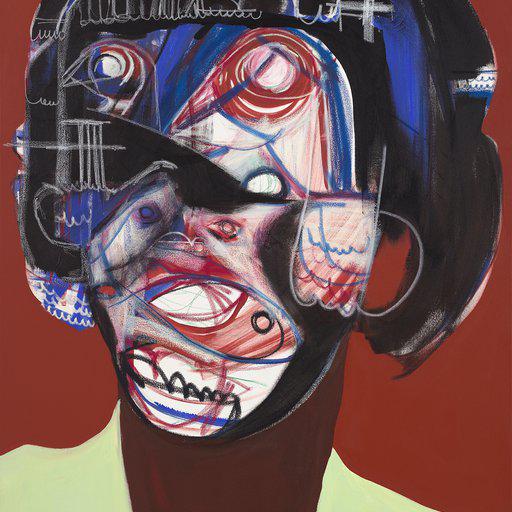

The highly acclaimed young American artist Celeste Dupuy-Spencer artist paints visceral, visionary, figurative works, which draw on her own personal fears, wider political and social pressures, as well as the existential conflicts within the human condition. The LA-based artist's blistering paintings, loaded with a complex mix of iconography, drawn from the real and the imaginary, have seen her artworld standing rise exponentially in recent years.

Dupuy-Spencer has been the subject of numerous exhibitions at such institutions as the Hammer, the Whitney (where The New Yorker referred to her as 'a standout'), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the ICA in Boston. The Whitney, the Hammer and SFMOMA also have Dupuy-Spencer works in their permanent collections, as does the Los Angeles County Museum; many private galleries and collectors have followed these institutions’ lead, making Dupuy-Spencer one of the most appreciated painters at work today. Anne Ellegood, who co-curated the Hammer show, says Dupuy-Spencer is set to become “one of the great painters of her generation.”

In this interview, published to celebrate her new Artspace edition (to benefit the The Center Benefit Auction , in support of The New York City Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center), the artist describes the forces at work in her paintings, which include a Marxist upbringing, a struggle with addiction, as well as her admiration for, and reinterpretation of, movements such as Impressionism. Her own family history plays a part in her work too; Dupuy-Spencer is descended from one of the founding families of New Orleans, and her father is the acclaimed novelist, Scott Spencer.

The new edition, When you’ve eaten everything below you, you’ll devour yourself/except in dreams you’re never really free , sums all of this up, with its struggle between earthly possessions, heavenly liberation and a possible hellishly bad end.

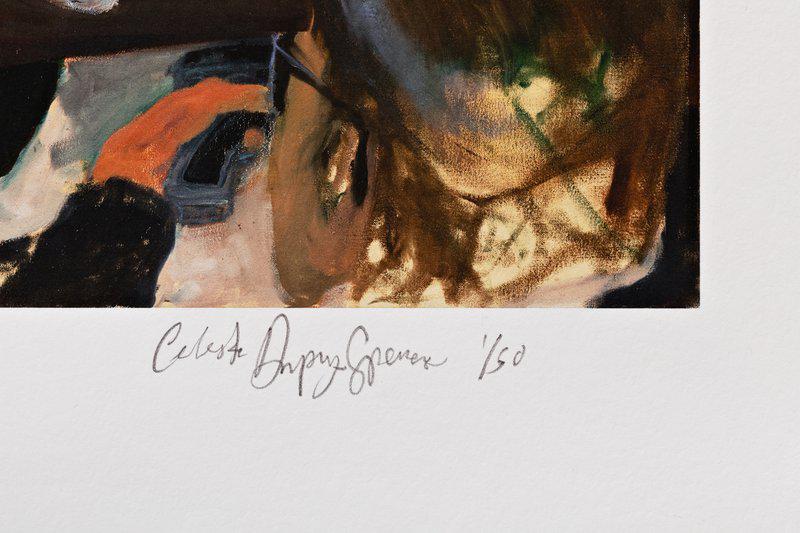

These 50 digital archival prints on Epson Hot Press Natural paper, are signed and numbered by the artist on the front. Read on to find out more from the artist who created this ravishing new work.

Tell us about how the original painting for this edition came into being I was in the last leg of working for a show at Max Hetzler gallery. Against my better judgement I pulled out a blank canvas when I should have been tying everything up. It happens every show and it always ends up to be the painting that I end up loving the most – which is lucky, because while I’m doing it I’m usually thinking this is a really baaaad idea!

The paintings that I was working on for that show were giant groups of animals racing off into oblivion and cities being engulfed by the ground. I realised it was an entire show of emotions and that I needed there to be a story. I needed there to be something solid, and so I wanted to make it about this part of our nature, this desperate need for wealth. I was really trying to paint something that’s impossible, which is what it feels like to be living in what really is the fall of human civilisation.

I don’t ever really go in with a plan; it’s sort of an act of faith. Sometimes it’s a composition or an idea. Then the painting unfolds on its own. This painting started with a composition triggered by a Tintoretto painting.

So is there a routine for you? I have a really strange routine. Which is that I really function very well in a dream state – exhaustion essentially. My normal one is a 26-hour day. So I often start working in the evening and then leave the following evening. And then I get a good eight hours sleep and then I do it again. I get a second wind and then a third. So I have different mindsets when I tackle a painting. It starts with the critical mind, where I’m intentional about what I’m doing, and ends with a dream state where I’ll be surprised when I stand back.

The critical moment isn’t necessarily when I start the painting it’s just the beginning of that ‘shift’. Like that first idea is how to get my foot in the door and then the ideas are cumulative. It’s like starting your life in a home with a tornado. First it’s a tornado and then it’s the clean up to get a house out of the debris. But I have to utilise the debris.

It’s almost like a spiritual or mystical practice. It feels highly collaborative, except that I don’t know who I’m collaborating with. There’s moments when the painting is rattling at the cage and I don’t even know what it looks like. All I feel is that I am providing a way for it to come out. It really feels like a magical project and a relationship with time.

There is a moment with all of my paintings where it really is me wrestling with material against a surface and I’m pushing and pulling and trying to remember how to make light and shadow and sculpt something. Then there’s often a moment all of a sudden where I make a mark and the canvas’s eye opens up and it’s looking back at me. And I really live for that.

Sometimes it’s literally just this other world on the other side. It’s magical. When that happens it makes me think there might actually be a place for painting in my worldview, and that I don’t have to get stumped by the politics of the art world and capitalism. And that, even if I don’t believe in fate, I was put on this earth to do this.

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer signing one of the 50 editions

The shape and motion of the body in your works is incredibly revealing, along with the eye for subtle, telling detail. Were you the kind of kid that sat and observed? Maybe it’s that plus being queer. I learned early on how to read the room. There were a lot of feelings in the house, I guess. But the other thing might be that it comes from autism or having to find a way into a place where I can understand people and what they’re thinking, because I don’t automatically understand what they’re thinking.

One of the things that I think is dangerous about how we are right now is this rejection of emotion for materialism. As someone who grew up Marxist I appreciate materialism. It’s hard to be a Marxist in the artworld! That's my whine for the day. But I think we often intellectualize things that should be felt, and I think that we’re in scary territory. So I feel strongly that either I could learn how to tamper that down, or try to find out what human beings are actually in doubt with, in terms of emotionality.

Obviously every painting is a little bit different, but one of the things that’s important to me as a painter talking about Americans, is that I never want to be standing on the outside of something pointing in, and describing what I think is in it.

I really want the viewer to be aware of how they thought they were going to view the painting. For example: with the insurrection painting I did after January 6, on the first look I really want the viewer to think, ‘look at these awful people storming the democratic palace’. But then I want them to be confronted with the way that they are. It’s like old school impressionism, where all of a sudden the viewer is implicated or their view is implicated.

In the case of this edition image, the viewer is maybe able to feel that they are standing in the righteous place, looking at others with enormous wealth and political ties, tear the world apart while surrounded by bottles of Champagne and art historical pieces. But the question it poses is: what are you going to do when there’s nobody left to blame, or to take all the responsibility? Because the circle is going to get smaller and smaller, and we have to find a place to be at peace with it or just stop doing it.

And that's important. We’re going through a moment right now where we’re pretty much top to bottom psychopathic. And it’s maybe because if we actually stopped to feel what it’s like to be alive right now, with all of the information that we have, plus what NASA tells us is in our future, and the statistics coming out of Africa, we’d pretty much lose our minds! And so actually there’s actually a lot to be said about finding a way to access people’s feelings center.

Did you always want to be an artist? When I was a kid what I actually wanted to be was an archaeologist – it was before I knew about colonialism or anything like that.I wanted to find out what it would have been like to walk around in the day to day. You see the paintings in Pompeii and you think you had an idea of how the people lived but then you see a piece of graffiti or the dog frozen in time, and you go, 'oh God I feel I know how it feels like. I feel like I’m standing there before Vesuvius exploded.' And that is magic actually. It’s like being a time explorer and a magician! So I think of myself as being a portrait or a representation of what it feels like to be alive right now for future archaeologists or spacemen or whatever.

What did you learn at Bard and what did you have to unlearn? When I went to Bard I didn’t really know anything really about art. I’d always painted and I’d always done art, as far as I can tell. My mom had art books and I went to high school arts, but then I dropped out and was a landscaper and went to Bard because I enjoyed painting. But I always assumed I’d go back into landscaping. So I went to Bard as part of their continuing study program that enables local adults to attend without paying much more than it cost to have us in class.

I just happened to have been a young adult there at a time when there were really amazing women running the art program - Nicole Eisenman, Judy Pfaff, and Amy Sillman - these people actually grabbed me and took me aside and said you are a very good painter, and you are queer. It is your obligation to take this seriously!

And it was the first time I’d actually heard it. I knew I was an OK painter. People had said I would probably be an artist in the school yearbook. But I didn’t know what contemporary art was; it was off limits to me. When I thought about art I thought about the Italian Renaissance. So when that happened and the professors confronted me it was life altering. And very loud!

I left Nicole’s office that day with a stack of books and Sadie Benning videos that I couldn’t see over the top of! Just tons of contemporary art. They sent me home with it and said, 'if you lose one of these we’ll kill you!' It was like Hogwarts or something.

And then you somehow became a heroin addict? What was that all about?

I went from Bard to New York City in the queer art world. It just seemed so perfect. Like everything was being added intentionally. And I always thought that everything that I was adding was going to stay added. And… it turned out that all of that had to be obliterated.

There was no party element to my addiction. I feel it can get alluded to as a party fashion thing. It wasn’t. It was a deep secret. When I hit bottom with that I was a complete blank slate. Everything I thought I knew about myself, about everything, just got wiped away. But I’ve learned to have an overwhelming gratitude for heroin, actually. I don’t know if I’d be alive if it wasn’t for…otherwise… because it was certainly something I’d reach for when I didn’t have any other tools. When I bottomed out on heroin it reset the art – everything. It took me by the ankles and just shook everything out. And I got to put things into place.

I just like myself so much more than I ever did. And I feel more engaged and more empathetic. So all of a sudden to have this enormous love and empathy for people including their failures - everything was just brand new - it was like being a five-year-old again.

The empathy that it perhaps gave you is reflected in the paintings. The reading can never be just black and white - in reality and metaphorically. I’m glad they come off that way because that’s really important to me. My fear is that I make yet another scapegoat for our worst angels, because that’s then the start of going into propaganda, in a way.

We’re so easily charmed into thinking like that. The way I see it is if we always want to be the good person we have a really hard time being flawed or wrong - we’re really not comfortable being wrong about things that we also know how to be the right way with.

And so I realise when I’m making these charged paintings I really run the risk of making something that again the viewer can dump all of their worst stuff onto. Like, right now I have a single insurrectionist in my studio whose parents are patting him on the back and sending him off with his AK47. And I just don’t want people to look at him and think, ‘look at that guy, I would never be that guy’.

The truth is that we have much more in common with ‘that guy’ than anything else in the universe. The universe is so massive and we’re among an uncountable amount of things that exist. Therefore the similarities between us and the insurrectionist, or monsters such as Trump or (Boris) Johnson are very close – we’re identical. This idea that we can separate each other ideologically it’s just not helpful.

So some people might then say, 'so Celeste is painting about empathy?' and that’s not it either. I don’t think it’s my place to tell somebody to forgive. When people hold positions that are wrong they don’t deserve forgiveness just because they are human. But all I’m asking is that we don’t scapegoat people.

We’re really touched that you have chosen to create this edition with Artspace to benefit The Center Benefit Auction . It’s a very democratic way of enabling more people to live with your work when they otherwise might not be able to Me too. I am really excited about this too for that reason. The paintings are so expensive and there’s not really much I can do about that, right? So I find myself basically only in communication with certain people. So to have the opportunity to have a beautifully printed edition of my painting that people can live with means the conversation can include more people essentially. It’s inspiring too and it’s broken open my thoughts about what’s possible to do with paintings.

Find out more and register your interest in this edition here.