Cecily Brown owes a debt of influence to Francis Bacon . As the British-born, New York-based, painter reveals in an interview with Robert Enright, reproduced in Phaidon’s new Contemporary Artist Series book, when she was coming up, “Bacon and de Kooning were still alive and I’m totally in debt to their work and, even more, the way they talked about it.”

Indeed, the links between these two artists run deeper than the surfaces of their canvases. As Phaidon’s new book explains, Brown’s father was the British critic and curator, David Sylvester, who worked with Bacon, managing exhibitions and authoring a book of interviews with the artist. Sylvester didn’t reveal he was Brown’s father until she was 2. However, as the book notes, “Sylvester had taken an active role in Brown’s life for much of her adolescence, and introduced her to the material of his life’s work, namely the art of Willem de Kooning, Francis Bacon and Howard Hodgkin , and at times the artists themselves.”

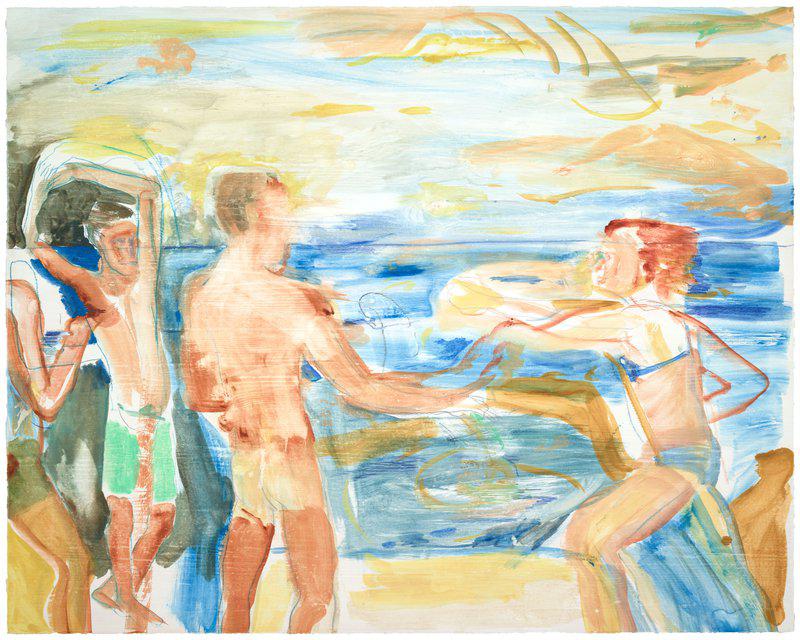

All the Nightmares Came Today

, 2012/2019, by Cecily Brown

All the Nightmares Came Today

, 2012/2019, by Cecily Brown

While, the aesthetic debt Brown owes to Bacon is fairly clear, the theoretical framework the older painter provided is pretty vivid in Brown’s mind too. Consider her thoughts on Bacon’s choice of subjects, expressed in an interview with the critic Jackie Wullschlager, also reproduced in Phaidon’s new book. “Bacon said the hardest thing is knowing what to paint. If you don’t have the physical urge, you can talk yourself out of it intellectually before you even pick up a brush. I don’t think in any other way. I have to be in the studio, I don’t have ideas unless I’m physically doing it.”

Of course, Brown, like Bacon, doesn’t reproduce her chosen subjects slavishly. In the following extract, she tells the art historian Courtney J. Martin what she thinks about the fine line Bacon and his British, twentieth century contemporaries trod between figuration and abstraction. “When you think about British painters – Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud , Frank Auerbach – they never really became abstract," she says. "There’s an abstraction within, but there’s still figuration. The danger if you’re more figurative, is that you can belittle things by describing them, or illustrating them. There’s always that fear. This is why I always say figuration is so much harder, because of that line you can cross into illustrating – just showing what something looks like.”

The Last Shipwreck

, 2018, by Cecily Brown

The Last Shipwreck

, 2018, by Cecily Brown

She also goes on to explain how she thinks Bacon exploited the glass used to frame his pictures “which refuses a single point of view; you have to move around as you look at them; you have to shift slightly,” and why the painter, so highly regarded an artist in Great Britain, wasn’t accorded quite the same status in the United States.

“Bacon is actually pretty flat, and of course he was very afraid of being an illustrator,” she says. “I think he relied on the glass a lot, but he’s clever in directing the way the viewer looks. You can’t just get it straightaway. We look at things so much in reproduction, and of course, in reproduction you don’t get any of that, you just get the flat image. So many Americans don’t get Bacon, and I wonder if you really need to see it in the flesh, because if you see it in reproduction, it’s so flat.”

Untitled

, 2014, by Cecily Brown

Untitled

, 2014, by Cecily Brown

The differences in the post-war experience on either side of the Atlantic also affected the way his work was received, she says. “Bacon can seem slightly histrionic and absurd, I think, for Americans. Whereas if you’re British or European, you grew up with that postwar sensibility. Our parents remember rationing. It was in the air when I was a kid. The further we get away from the 1970s, when I grew up, the more I realize that we were actually closer to the war then than we are to the 1970s now. What, to Americans, might seem slightly bizarre in Bacon or Freud is that it’s too angsty. In abstraction, there’s room for anxiety as well as this sort of sublime, because the mood shifts: you can look at a Rothko and it’s more about what you bring to it.”

Today, Brown’s own lived experience is distinctly North American; her studio is in New York. However, she still relies on the same techniques Bacon employed, back in grimy old 20th century London. “I’ll use news photographs quite often, and even reproductions of paintings,” she says. “I use photographs of paintings, like a lot of artists – famously Bacon, who didn’t actually see the pope painting in Rome that he worked on thousands of times. He used a photograph. There’s something about working from a reproduction rather than from the actual work that distances it.” That appreciation for distance is just one of the things that brings Bacon and Brown’s work together.