A cynic might call Art Basel’s Unlimited section the Sam’s Club of contemporary art—the bigger-is-better commercial wonderland of super-sized installations, amped-up aesthetics, and IMAX-style video installations. But this year, at its most gargantuan scale to date with 88 projects in total, the fair’s curated component is also a great place to consider the state of spectacular art as a category.

We all know that museums and other art spaces, now competing with the Internet for visitor eyeballs, are ever-more dependent on immersive, thrilling, be-here-now art offerings that can woo crowds and keep them absorbed and Instagramming. So, what kinds of artworks are most effective in accomplishing this? Here are several approaches gleaned from the Unlimited section.

Technological Wonders

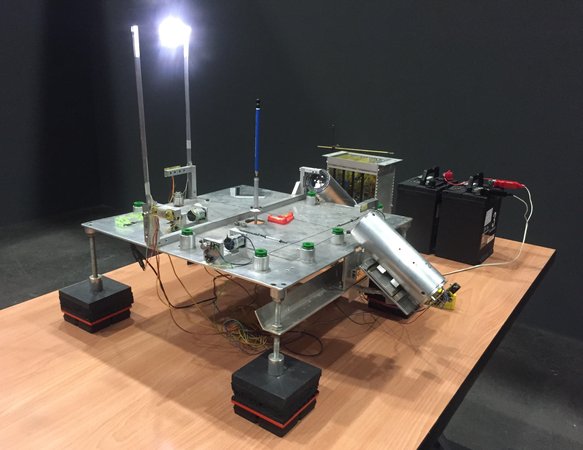

Using a gyroscope-like machine and two motion-detecting optical scanners, Steven Pippin's Ω = 1 (2003-13) balances a pencil on its sharpened tip by continually adjusting its base to adjust for the direction the writing implement wants to fall. Meant to illustrate an astrophysics princple of spacetime, the piece is a marvel of functionless technological ingenuity (aka art), and a classic of its kind.

The winner of the latest BMW Art Journey award, the Hong Kong artist Samson Young dressed in military fatigues and stationed himself atop a platform in the exhibition hall with a high-powered sonic canon used to bloodlessly disperse crowds, instead configuring it to play bird sounds across the hall to a second-floor installation (accessible by an elevator) that mimics a dark, oppressive prison cell of the kind where a political dissident might be detained.

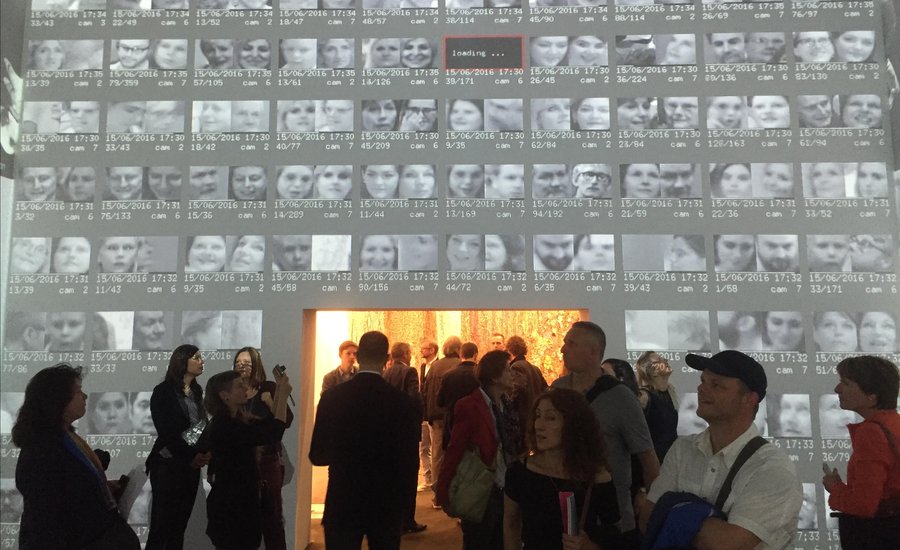

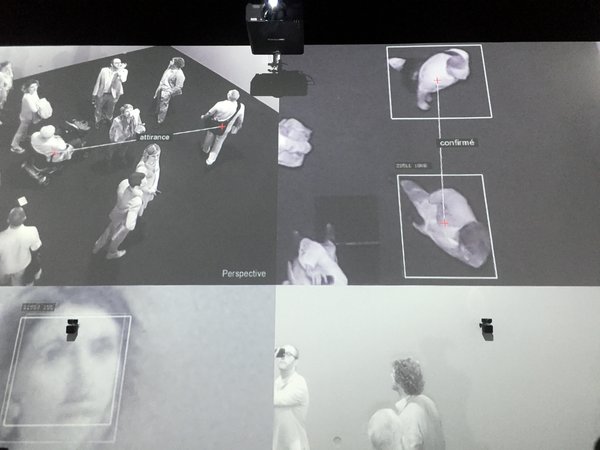

In a corner at the far end of the exhibition, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Krzysztof Wodiczko had the future-shock standout of the show, and one of the best works on view in Basel this week: a room filled with facial-recognition cameras that immediatly register a viewer as they walk in, analyze their body positioning to ascertain their relationship to others in the room, and put their face up on the wall in a kind of visual dossier. Uncanny and unsettling, it should be toured from museum to museum as a public service announcement.

Ok, so glow-in-the-dark paint isn't all that high-tech, but Jacqueline Humphries's installation of four effulgent paintings provides viewers with a giddy electrical charge.

Mysteries

Hans Op de Beeck's opulent recreation of a collector's grand living room—featuring a lily pond that recalls Henry Clay Frick's—is a captivating riddle: Why is everything grey? Who are these half-naked women and boys? What transpired at the apparently ill-fated party that scattered drinks and cigerette butts all around? Visitors could not get enuogh of this masterful enigma.

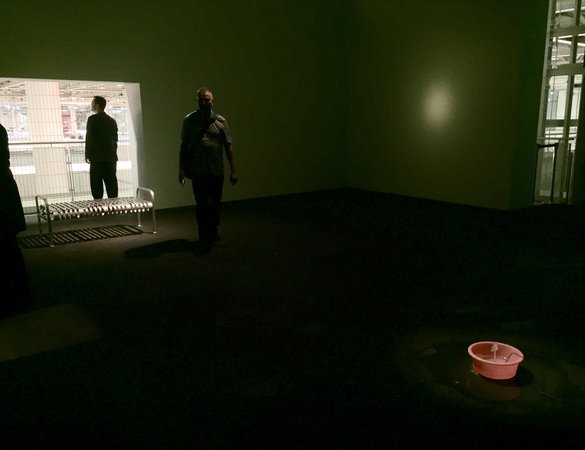

Pamela Rosenkranz has been using blue and pink in her recent work, such as her all-pink pool room at the last Venice Biennale's Swiss Pavilion, and this cheekily titled installation—Blue Runs—pours an unending stream of neon blue water from a modern faucet. Why? The answer has to do with the post-human, we're guessing.

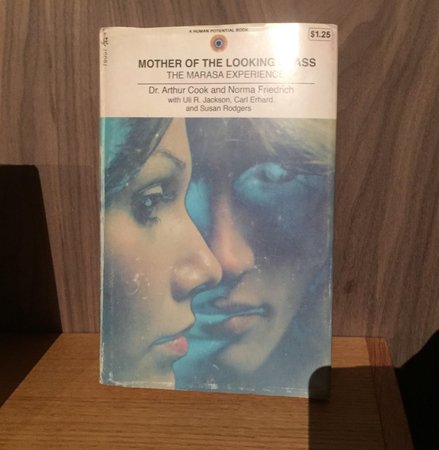

In their latest installation chronicling the utopian underground of their fictional San San International city, Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe have produced more of their tantalizing cultural artifacts relating to the "Vortice Science of Behavior," the "Human Potential" movement, the potent psychotropic drug Marasa, and other elements of their artfully limbed but just-out-of-reach world.

Trisha Donnelly's contribution to Unlimited has no accompanying curatorial statement, which just doubles down on its tantalizing opacity. It may have to do with computer circuitry, like some of her previous work, but this implacable image projected on the wall was not revealing its secrets.

Wraparound Multiscreen Videos

One of the exhibition's greatest achievements, William Kentridge's Notes Toward a Model Opera employed three screens, maps, heavily armed ballet dancers, infectious music, animations, and brilliantly deployed Maoist texts to tell the story of the pitiless search for model soldiers ("Be a stone to sharpen everyone else's knives"), farmers, workers, and other indoctrinated comrades during the Cultural Revolution.

Under-known Pictures Generation artist Gretchen Bender's 24-screen "electronic theater" piece Total Recall from 1978 blares commercial imagery, military propaganda, Hollywood entertainments, and other cultural ephemera from an era where people worried about the brainwashing influence of mass media—rather than today's preoccupation with surveillance and information-gathering, as addressed by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Krzysztof Wodiczko's piece.

Another standout of the show, Kahlil Joseph's m.A.A.D. from 2014 used two screens, an affecting Kendrick Lamar soundtrack ("Promise that you will sing about me"), documentary images of lynchings and riots, and scenes of everyday life and death to tell the story of Compton. It's gripping.

Feasts of Close Looking

Running along all four walls of a room, the 50 drawings of Mike Kelley's 1989 Reconstructed History series offers a chance to spend some time with the late artist's back-of-the-classroom approach to American history.

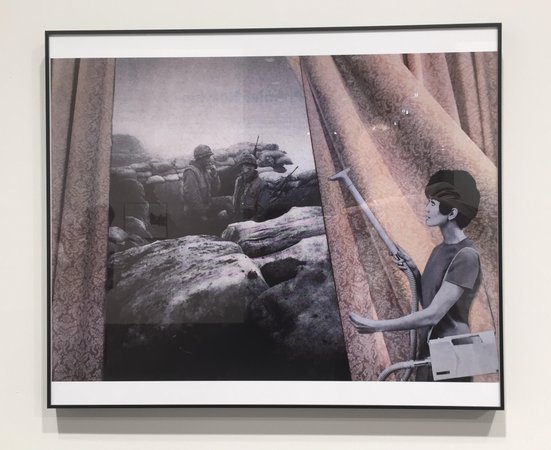

Martha Rosler's seminal series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home from 1967-1972 combined imagery from the war in Vietnam with spreads of domestic contentment from House Beautiful magazine, and all 20 photomontages were on view here, inviting viewers to delve into an all-too-relevant historical moment.

In the vein of really close looking, the Indian artist's Prabhavathi Meppayil absorbing display of readymade brass and iron goldsmithing molds called viewers in close to admire impeccable craft—an instance of the teeny-tiny making a large impact through profusion.

Gigantic, Engulfing, Eye-Swallowing Paintings

Tobias Pils

Alan Shields