The artist can take on a variety of roles in the popular imagination: visionary, rebel, esthete, prankster, troublemaker, and even, come to think of it, purveyor of a special kind of luxury good. Today our topic is a little different. Today let's consider the artist in the role of do-gooder.

Artists just want to help. Nary a day goes by without the announcement of some event or appeal demonstrating the apparently boundless good will of the art world. "Engages in social commentary" has become a box that you check off on the aesthetic report card. This form of beneficence is common to find among artists these days—perhaps in part due to their urge to counter a similarly widespread suspicion, that art is in fact an amoral endeavor.

At the simplest level, art is enlisted for fundraising. One major event last month was the gala at Cipriani 42nd Street for Americans for the Arts, which raised some $800,000 for the national lobbying organization. As an organization, AFTA is a Pollyanna booster for arts education, practically guaranteeing that art improves the quality of everyday life (which we all know it does, of course). The group even encourages young people to pursue careers in the arts. None other than Barack Obama is on board. He sent the nonprofit a congratulatory letter on the eve of the event, extolling art for having "the power to disrupt our views and enrich our lives."

This year's AFTA gala honored the 19-year-old movie star Dakota Fanning, who charmed the audience and thanked her mother, and the 88-year-old guitar idol B.B. King, who was introduced by his equally venerable fellow bluesman Buddy Guy. Sculptor Joel Shapiro was also honored, and the painter Will Cotton enlisted to design the table centerpieces and the backdrop for the stage.

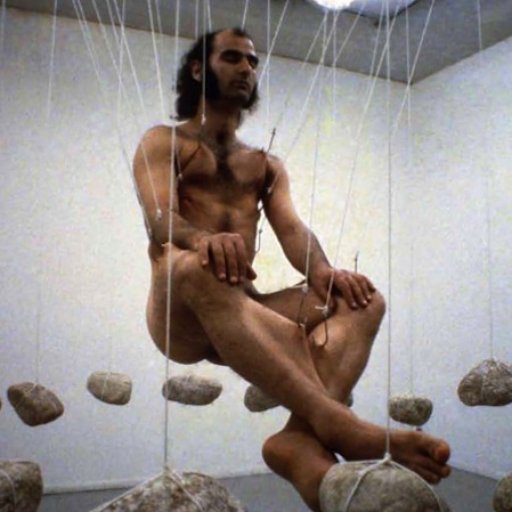

Fall is benefit season, which has expanded to such an extent that generous artists can spend half their time making things to give away. In my capacity as a painter, I myself was given two such opportunities. The first, a hullaballoo titled "Take Home a Nude," was held at Sotheby's and featured costumed performers on stilts as well as plenty of nakedness. It raised a record $900,000 for the New York Academy of Art, a school once affiliated with Andy Warhol and now ensconced in its own extensive quarters on Franklin Street in TriBeCa.

True, raising money for an art school may seem a little self-serving. Better was Artwalk NY at 82 Mercer Street in SoHo, which raised $1,000,000—a new record—for the Coalition for the Homeless. The gala boasted an interior design by Dolce & Gabbana, hors d'oeuvres from a host of top-end chefs, and celebrity sponsors like Alec Baldwin and Richard Gere (and a painting of a cheeseburger by me).

This kind of thing is "political art" without much politics. Needless to say, efforts by artists to do good are hardly limited to raising money. Artists seek the good directly in their work.

Some artists embrace working methods that are themselves idealistic. The Bruce High Quality Foundation has actually won market success through its collaborative generosity, which includes high-profile open-call exhibitions and an ongoing school (where David Salle currently teaches a class on art criticism, for example), all at no cost.

Others—too many to mention, really—take social and political issues as their subject. Cooper Union has just opened "Emissions: Images From the Mixing Layer," a show devoted to climate change, atmospheric methane, and fracking, with works by Colleen Fitzgibbon, Ruth Hardinger, Joe Lewis, Christy Rupp, and Rebecca Smith. The provocative and successful summer-long run of Thomas Hirschhorn's Gramsci Monument, a kind of DIY community center set up in a Bronx housing project, needs no additional comment here. Even Banksy, whose monthlong New York "residency" captivated the tabloids and art blogs—an interesting alliance, that—managed a performance promoting animal rights, and anonymously dropped off a painting at Housing Works, which promptly auctioned the thing off for an awesome $615,000.

Hell, political art has gotten so popular that universities are even teaching the stuff—and at the graduate level, no less. Queens College and the Queens Museum are teaming up to offer in spring 2014 an "MFA concentration" called Social Practice Queens, which supposedly "integrates studio work with social, tactical, interventionist, and cooperative forms... of art and social action." As it happens, the Queens Museum under its executive director Tom Finkelpearl has become known as a leader in activist community programming. The museum places a particular emphasis on immigration issues, prompted in part by the borough's status as one of the nation's most ethnically diverse.

The artist Walid Raad, who coincidentally is my downstairs neighbor, has recently begun circulating via email a project titled "52 Weeks of Gulf Labor." Each email presents one or more artworks by a member of the international coalition of artists who in 2011 called for a boycott of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi to protest the treatment of the migrant workers building the exotic new museum. (For details, visit www.gulflabor.org).

Hirschhorn contributed the second installment, and the Swiss artist, who is both celebrated and criticized for his bleeding-edge approach to social issues via his large art installations, wrote an eloquent text he titled "My Guggenheim Dilemma." The root of that dilemma, he says, is his "belief and conviction that Art, as Art, has to keep completely out of any daily political cause in order to maintain its power, its artistic power, its real political power."

We have long had this objection from both the right, where it might be expected, and the apolitical, formalist middle. The art-for-art's-sake argument is a little stranger coming from the left. The unease that persists between art and political action, this "dead end" as Hirschhorn calls it, is also the animating spirit of art critic Ben Davis's popular new collection of essays, 9.5 Theses on Art and Class (Haymarket). Like Hirschhorn, Davis sees the artist as a creative force, and maybe even as an exemplar of authentic and unalienated labor. Still, he has little hope for political art detached from the kinds of sustained, goal-oriented political activism that could bring about true change. It seems unlikely, however, that the discussion will deter the artists who just want to do good.