As I walked past the stacks of DVDs that lined the entrance to Zach Feuer Gallery last week as part of "You Are Standing In An Open Field," I overheard an exiting high-heeled gallery-goer telling a friend about the show, Canadian artist Jon Rafman’s first solo outing in New York. "It was strange," she said. "It made me feel uncomfortable. Something just wasn't right." I was immediately excited. After seeing the show, I understand what she was talking about. Rafman's work is uncanny, inviting the viewer into a world that is neither digital nor real, but an overlapping combination of the two.

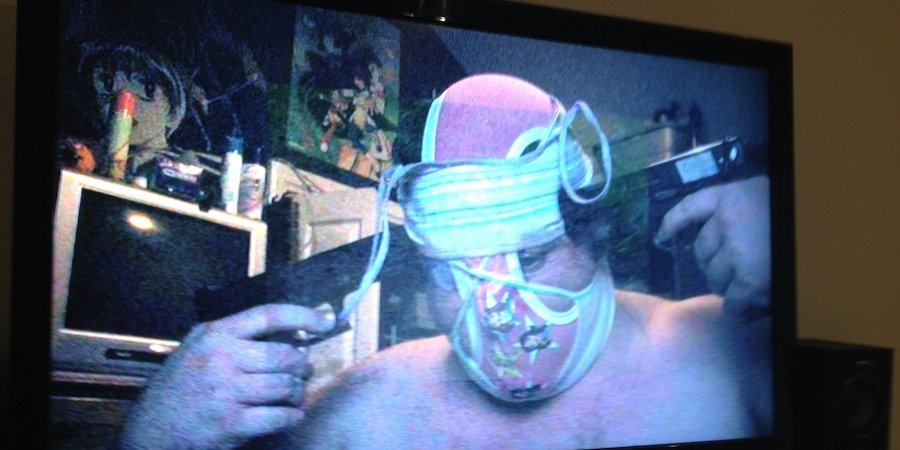

The first work I encountered was a particularly dark video, Still Life (Betamale) (2013), which portrays a world obsessed by the digital screen and the attractive fetishes it offers. The film culminates in a still of an obese man with girls' underwear wrapped around his head holding two handguns to his temples. This disturbing image flashes again and again throughout the video, which also features strange creatures and splashes of animé—made stranger still by the trickling experimental music by Oneohtrix Point Never. The artist seemed to be presenting a dystopian scenario: that as we move deeper into our screens, the real world around us is dying, leaving us only our virtual fantasies while debasing our humanity. This idea colored my view of the rest of the show.

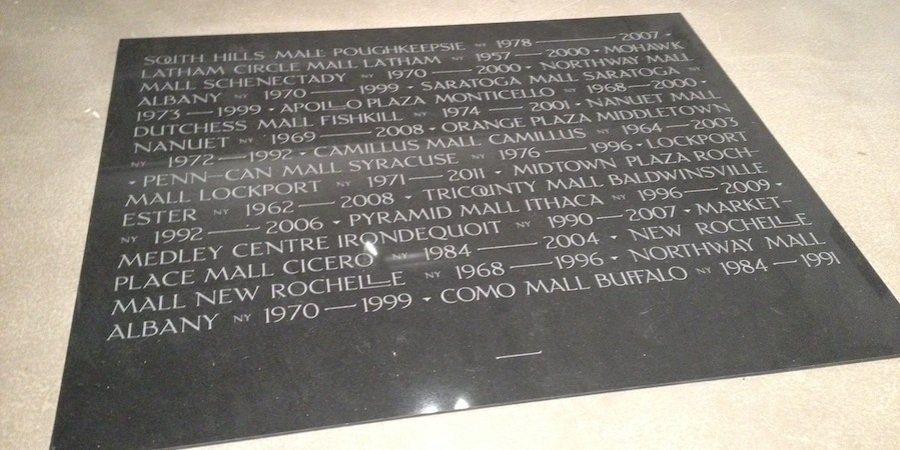

In the gallery, Rafman creates a sham human history. A piece on the floor, Plaque (2013), contains a list of fallen New York State shopping malls—presenting an opportunity to mourn the loss of Rochester's Midtown Plaza and Albany's Northway Mall, among other defunct commercial enclaves. With acid sarcasm, it puts consumerism in its place. In another piece, Codes of Honor (2011), Rafman furthers his indictment of cultural complacency by displaying bloody shootouts in the massively popular video game "Code of Honor" and having the victors narrate their experience. Are these the heroes we should celebrate? The question he poses is easy, but effective.

Messing with the viewer’s sense of history a little more, Rafman’s Inventory (Hands) and Inventory (Head) (both from 2013) display spears, knives, and futuristic looking guns affixed to a board in the former and tribal masks mixed with sci-fi combat helmets in the latter. These artifacts display more clutter from the digital realm, combining objects from human history with fictional weaponry from video games. Shown in a format reminiscent of an ethnographic museum, the artworks propose an unsettling scenario in which our species's evolution leads into a sanguinary virtual realm.

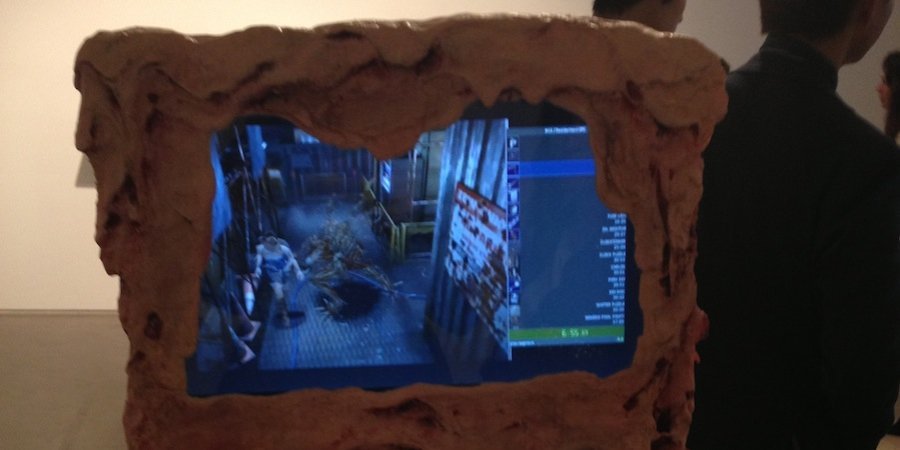

The centerpiece of the show is I Am Alone But Not Lonely, a large 2013 installation made of trash and various bits of cultural detritus, covered in volcanic ash. Venturing into its midst, I am caught in yet another landscape stuck between fantasy and reality. The objects in the installation are mundane: beer cans, half-eaten lunches, crates, office chairs, posters, shelves, PlayStation remote controls, Yu-Gi-Oh dolls, a dinosaur (and other figurines), and, as the main event, a computer and television screen. This is a place well lived in by lonely people—although, because of the communities available on their screens, they are not completely alone. By cloaking the space in volcanic ash, Rafman portrays it as a disaster site, like a living room in Pompeii after the eruption.

The work’s title, I Am Alone But Not Lonely, is also the title of a song by Mary Chapin Carpenter. It goes, "There are moments in time that are meant to be held / Like fragile, breakable things / There are others that pass us, you can't even tell / Such is their grace and their speed / And this one is gone in the blink of an eye." Sorting out which moments matter and which should be forgotten, which are real and which are illusory, is the challenge of this show.