We opened "Calder & Fischli/Weiss" at Fondation Beyeler just two weeks ago, so it was a satisfying déjà vu to return to Basel for the fair and see the show again this week. (I gave so many tours that I lost my voice!)

I've been gratified by the momentary confusion that came out of pairing Calder with the beloved "contemporary" Swiss artist duo—the resulting dialogue has been overwhelming and wonderful. I continue to be inspired by the many curatorial subtexts of this unexpected show.

1.

Francis Picabia

La toréador Belmonte, c. 1940/41

Michael Werner Gallery

I landed in Zürich last Monday morning and went directly to the Kunsthaus to see their wide-ranging Picabia exhibition with much excitement and also trepidation. It's an important moment for Picabia, and Michael Werner had two other great paintings by the artist in his booth. But this less important portrait is the one that fascinates me.

Because the bullfighter Belmonte had a foreshortened leg, he couldn't leap in the bullfighting style typical of his day. So he turned his limitation into what would become a new style, literally standing his ground in the arena in fierce defiance of the bull, thus changing the sport forever. At first I thought the protagonist's clown mouth and lips were some sort of perverse Picabian joust, but upon seeing a photograph of the athlete, I realized Belmonte was simply a natural Picabian subject.

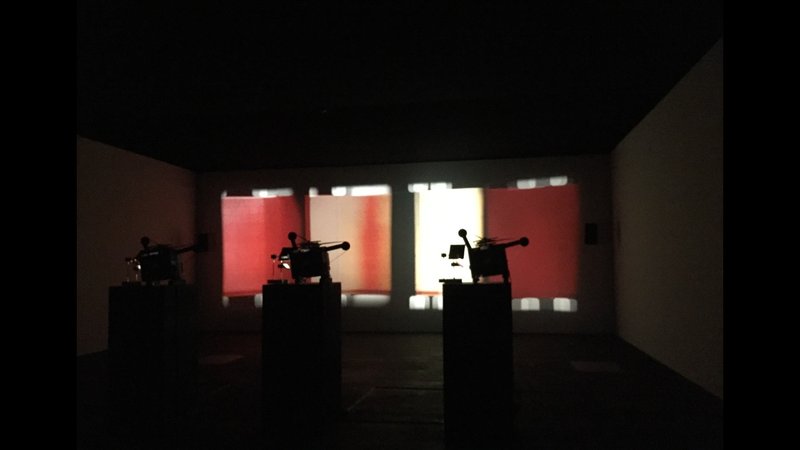

2.

Paul Sharits

Dream Displacement, 1976

Art Basel: Unlimited

I first discovered Paul Sharits's work at Greene Naftali Gallery in 2009 in a show curated by Jay Sanders, now the Whitney's curator of performance art who just so happens to be working on a Calder project.

While many will relate Sharits's work to Abstract Expressionism, and Rothko in particular, my experience of it resonates with Calder's three-dimensional, wall-mounted paintings in motion from the mid-1930s. (By the way, there is a virtually unknown and excellent example at Fondation Beyeler, which before this year was last seen in 1937.)

Sharits's stunning work from 40 years ago is extremely emotionally charged, almost physically dizzying, incorporating the startling sonic interludes that break your reverie as you view the four-projector installation. He died very young, and I've often wondered how his work would have developed in the information/digital age.

3.

František Drtikol

Howard Greenberg Gallery

I find this photograph from 1927 wonderfully romantic, yet without being overly sentimental. For those of us who still desire a connection to the historic obsession of beauty, this is for you!

The process of pigment printing makes for the richest possible tonalities, and therefore the highest aesthetic value. Drtikol's works have always been prized, but in recent years their value has risen so meteorically that they are now sadly out of my reach.

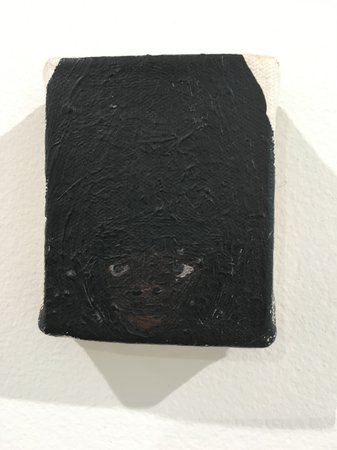

4.

Chris Ofili

The Chosen One, 1998

Victoria Miro Gallery

Of course it is preposterous to think that our bright nation might slide into the doomed dictatorship of Trump, but this diminutive work by Ofili at Victoria Miro's booth reminds me of a time not so long ago when New York's Mayor Giuliani tried to censor the artist's "sacrilegious" elephant dung and vaginal lip butterflies from this artist's exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum.

Easy to miss due to its tiny size (approximately 2" x 3"), the mysterious portrait is sensationally inspiring for its subtle elegance. With its cryptic title The Chosen One, this work is small enough to grab and run with if the world descends into a fascist Trumpian burnout.

5.

Tunga

Eu, vôce e a luna (Me, you and the moon), 2014

Art Basel: Unlimited

Visiting Tunga's sprawling studio, built vertically, favela-style, on the hills outside Rio, was an adventure. Tunga always had a bit of Amazonian shaman to him, and losing him to cancer two weeks ago, at the height of his artistic powers, is a veritable tragedy. But the extremely ambitious installation presented here at Unlimited is a conjured distillation of his various bodies of works. The piece alludes to unseen forces at play, facilitating access to things few of us can comprehend, while still resonating deeply with the physical body and, of course, dear Tunga's roots in performance art.