Expressionism emerged at the beginning of the 20th century as an artistic response to their Modernist malaise, an increasingly apathetic relationship with the physical world as a result of industrialization, urban growth, and other sometimes drastic societal shifts. Rather than simple mimesis of the natural world, the Expressionists chose to radically distort the forms and colors of the world in their raw depictions in order to arouse an emotional response from their viewers.

Much later, in the heady times of the 1980s, painters used this same strategy to move away from the aloof stoicism of some of the movements that came before, giving rise toNeo-Expressionism. The Neo-Expressionists returned expressiveness and raw emotion to art, and in particular painting, using it as a channel through which they could command the world that they lived in. In this brief essay from Phaidon'sArt in Time, we learn about how the artists of this movement channeled their despair and deep introspection into fervently forcible work.

[Click Here To Browse Neo-Expressionist Works On Artspace]

The 1970s and 1980s saw a Neo-Expressionist surge that raged in defiance of the conceptual cool of Pop art, Minimalism, Conceptual art, and Postmodernism. Artists returned to emotional content conveyed through instinctual mark-making, subjective color, and distorted forms, as found in early twentieth century Expressionist movements, such as Fauvism, Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, and in abstract forms in mid-twentieth-century Abstract Expressionism.

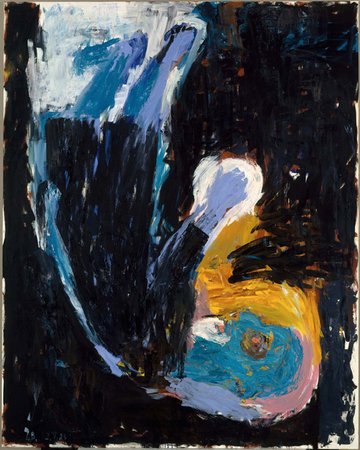

George Baselitz's Man of Faith, 1983

George Baselitz's Man of Faith, 1983

Although in the 1930s Expressionism was persecuted and labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis, Germany paradoxically became home to expressionist masters such as Georg Baselitz after the end of World War II. Baselitz (b. 1938) led the return to expressionism in Europe as early as the late 1950s, and his entire oeuvre has been emblematic of Neo-Expressionism. Man of Faith stands upside down before us as if in a world gone mad. His face and limbs glow with otherworldly blues and purples, his frenzied eyes mesmerize us, an aura of yellow and pink emanates from his face. The rest of the canvas is densely filled with bold, instinctual marks like the harsh black lines of German Expressionist woodcuts in the first decades of the twentieth century. Baselitz did not paint the figure normally and then turn his painting upside down when he finished, rather he actually painted the figure upside down, a spatially disorienting method of working. The painter’s mark in these works becomes a sign orienting him in an inwards quest to find an emotional self.

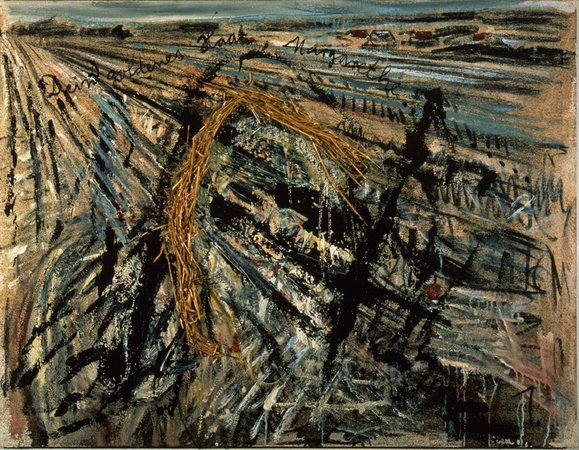

Anselm Kiefer's Your Golden Hair, Margarete, 1981

Anselm Kiefer's Your Golden Hair, Margarete, 1981

Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945) uses his art to confront German responsibility for the Holocaust and World War II. The pair of canvases comprising Your Golden Hair, Magarete, and Your Ashen Hair, Shulamite (1981) are based on poems by Holocaust survivor Paul Celan. The former refers to the blonde-haired blue-eyed ideal of the Nazis, the latter to Jewish women killed in the death camps. Kiefer renders the German landscape, once a source of pride for the Nazis, as expressed in their “blood and soil” rhetoric, a modern place of shame and emptiness. The real straw collaged onto the Magarete canvas references alchemy: a hope that this base material could be transformed into gold. In Shulamite, by contrast, the charred black fields and ashen landscape signal despair.

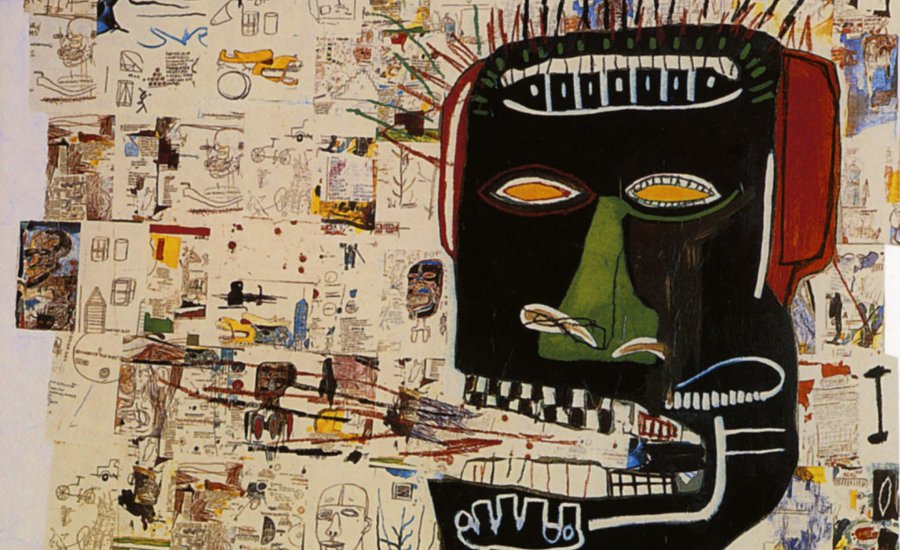

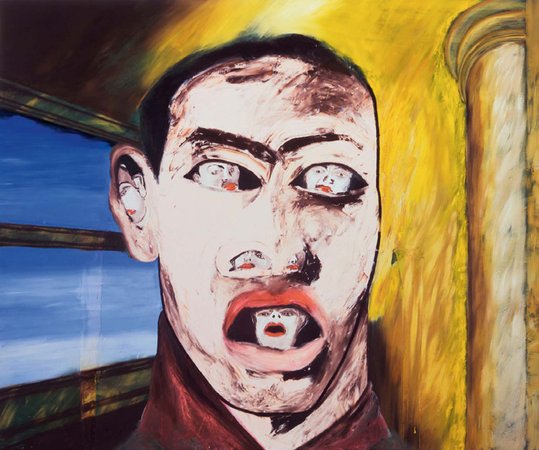

Francesco Clemente's Untitled, 1983

Francesco Clemente's Untitled, 1983

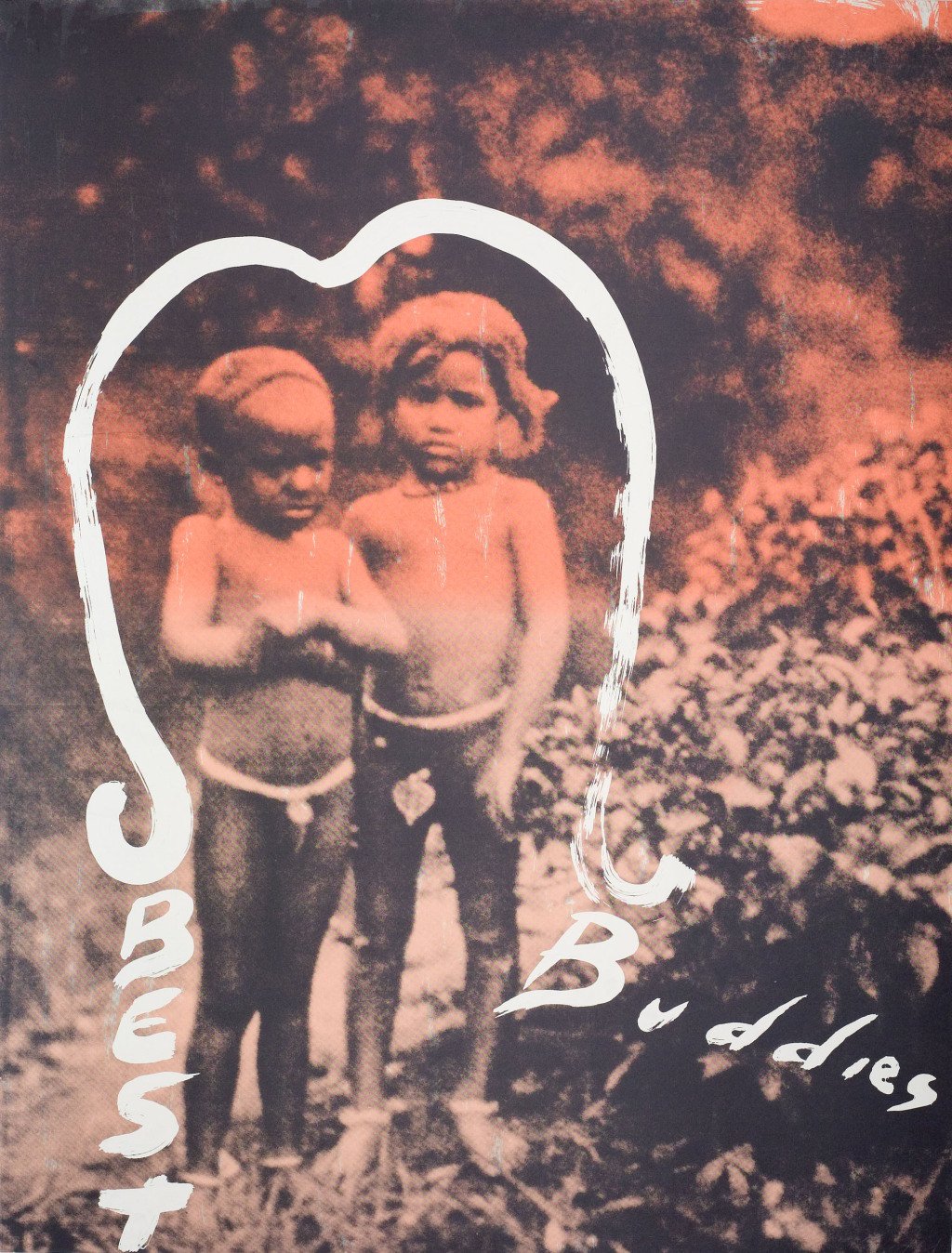

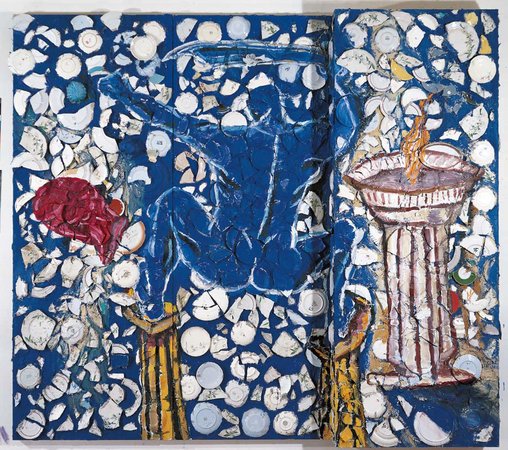

In order to encourage West German citizens to move to West Berlin, the government offered incentives such as exemption from mandatory military service. As a result, a free-spirited culture of art and music developed in the city. The revival of expressionist themes was also inspiring artists elsewhere in the Western world, moreover. Untitled, a self-portrait by the Italian Francisco Clemente (b. 1952), is the ultimate in interiority. Looking into the orifices of this self-portrait we see more self-portraits: fragments of the self-making their shocked and shocking appearance. Conversely, American Julian Schnabel (b. 1951) synthesized expressionist traditions with Postmodernist appropriation, as seen in his Blue Nude with Sword, which echoes Matisse’s late cutouts. The aggressive mark of expressionism is reinforced by actual broken ceramic plates affixed to the canvas.

Julian Schnabel's Blue Nude with Sword, 1979–80

Julian Schnabel's Blue Nude with Sword, 1979–80