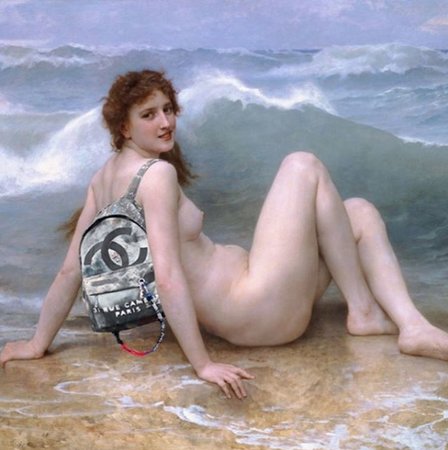

If you're caught up on all things hip and happening, you've likely noticed a recent trend that incorporates art historical references into contemporary art and fashion. Just look at Gucci's Fall 2018 runway show; or Dr. Marten's "Artist Series" collection featuring classics works by Hieronymous Bosch , J.M.W. Turner, William Blake and Di Antonio on their signature chunky boots (clearly they have a grasp on their predominantly art school student-based audience); or Opening Ceremony 's capsule collection of René Magritte apparel; or Chris Rellas's lauded Instagram @copylab, which features art history's most iconic images (like, say, Vermeer's 1665 Girl with a Pearl Earring edited by Rellas to appear as if the subject is wearing a Chanel earring).

"The Wave" by William Adolphe Bouguereau. Edited with Chanel Canvas Graffiti Backpack by Chris Rellas, Image courtesy of @copylab

"The Wave" by William Adolphe Bouguereau. Edited with Chanel Canvas Graffiti Backpack by Chris Rellas, Image courtesy of @copylab

The past few years have seen a lot of these new-age X classical cross-breeding. At this year's Independent Art Fair alone, we saw a number of classically inspired contemporary works, from Elaine Cameron-Weir's sculptural works that drew to mind delicate Baroque drapery; to Hans-Peter Feldman 's modified 19th-century aristocratic paintings, onto which he painted small subversive red clown noses and lipstick smears.

The works of old masters in particular—a term which, to sum it up briefly, generally refers to (white male) European painters working around the Renaissance-era (like da Vinci, Raphael, El Greco, etc.) who painted figurative, highly realistic works—have seen a steady rise in contemporary culture, and it doesn't seem like these oldies-but-goodies are going anywhere any time soon. (Need I refer again to Salvator Mundi , the alleged Leonardo Da Vinci painting that sold for $450 million back in November 2017 at a contemporary auction at Christie's?)

Hans-Peter Feldmann, Two Girls with Red Noses, Image courtesy of 303 Gallery

Hans-Peter Feldmann, Two Girls with Red Noses, Image courtesy of 303 Gallery

This wasn't always the case though. Back in 2016, New York Times writer Scott Reyburn reported that sales for works by old masters were dropping significantly: "In 2015, old master auctions had declined to $561 million, while equivalent sales of contemporary art stood at $6.8 billion, according to the 2016 Tefaf Art Market Report."

And let's be honest: the dropoff isn't that surprising. It's pretty hard for Remrandt's chiaroscuro to compete with the aesthetically alluring works of say, Yayoi Kusama . In a world so inundated with imagery, and a population with an arguably diminished attention span, it's easy for the subtlety of an old work to get overshadowed by a bright, whimsical one. So, much like the rebranding of Hush Puppies from drab to fab in the '90s, curators have begun to implement new curatorial practices, in an effort to make historically significant works relevant again. And what better way to incite a direct relationship between the works of the old masters and modern and contemporary artists than to literally hang them side by side?

From left to right: Tullio Lombardo, “Young couple,” 1505; Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled (Perfect Lovers),” 1987-1990, Image courtesy of the Kunsthistorisches Museum

From left to right: Tullio Lombardo, “Young couple,” 1505; Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled (Perfect Lovers),” 1987-1990, Image courtesy of the Kunsthistorisches Museum

"The Shape of Time," an exhibition currently on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, does exactly this: pairing modern artworks with the works of the Old Masters. Kerry James Marshall is shown alongside Tintoretto; Peter Doig with Breugel; Franz West next to Caravaggio; and Felix Gonzalez-Torres with Tullio Lombardo; to name just a few. The show aims to create "confrontational encounters that will catapult [the Old Masters] from the seclusion of five millennia of art history and illustrate their relevance for today." This encounter is intended as a collaboration of sorts, as curators write "for the first time ever, they will team up with works produced by non-European artists in modern media such as photography, film, and installations."

In the same vein, New York's Met Breuer just opened an exciting new exhibition called "Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now)." The show (on view until July 22) features 120 sculptural works that span seven hundred years (from 14th-century Europe to the "global present") and from art history's biggest names like Donatello and Rodin to contemporaries like Robert Gober and Jeff Koons . Artists have long been fascinated with the human body, replicating and abstracting it in an effort to understand the distinction between life and representation. Sensual, grotesque, beautiful, and revolting, the human body continues to fascinate and confound us. "Life Like" reminds us of the pleasure and confusion that has pervaded humanity's understanding of itself for centuries.

From left to right: Mask of Anna Pavlova, Malvina Cornell Hoffman, 1924; Untitled, Robert Gober, 1990, Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

From left to right: Mask of Anna Pavlova, Malvina Cornell Hoffman, 1924; Untitled, Robert Gober, 1990, Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Two terms we've been hearing a lot lately in describing these sorts of curatorial endeavors are "transhistorical" and "cross-generational." Put simply, these terms refer to a blend of old and new art. ( How old and how new seem to be pretty much up for interpretation––the span could be a hundred years, or thousands and thousands of years). Noticing these trends toward transhistorical curation the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem and the M-Museum in Leuven started the "Transhistorical Museum: Objects, Narratives, and Temporalities," a research project and forum dedicated to discussing the trend of transhistorical exhibition practice, defined as "a diverse range of curatorial efforts in which objects and artifacts from various periods and art historical and cultural contexts are combined in display, in order to question and expand traditional museological notions like chronology, context, and category."

Basically, museums are increasingly dismantling the tired encyclopedic arrangement of art objects in order to incite new dialogues and insights that challenge our historical assumptions. The Transhistorical Museum's goal is simple: it aims to "look at the concepts that undergird the transhistorical, describes the theoretical horizon it relates to and illuminates the practical applications it has fostered, thereby providing the grounds for further research and practical applications." By breaking down the barriers that divide historical art and contemporary art, each is given space to be reassess the object in a larger context.

In an interview with The New York Times , art historian Suzanne Sanders (who organized the "Transhistorical Museum" conferences in 2015 and 2016), stated of the term, "It can be ‘trans’ in all these senses of the word... from across history, to trans-disciplinary or queer, or just to represent things in an inclusive way, to find a balance between acknowledging and addressing points of view.”

They say going to a museum is like visiting a group of old friends. But once you get to know someone so well, how much do you really see them? Transhistorical curation allows us to see works we know in a new light––and continually discover something new. It makes us look at art like an artist, noticing the links and connections and influences between the current time and the inextricable past.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The Art Market is Growing Quickly Online (& Other Findings from the TEFAF Report)

The New Manifestos: 6 Artist Texts That are Defining Today's Avant-Garde