What's the connection between a looped high-def video of a carving knife, a row of tall, narrow convex black mirrors, and a hundred-foot-long scroll swarming with shimmering iridescent colors? They are all photographs according to no less an authority than the International Center of Photography (ICP), where they are featured in the exhibition "What Is a Photograph?" on view through May 4.

On first thought, the answer to the question posed in the title may seem elementary. I reflexively fell back on a facile definition that I likely picked up in a high school photography class, something like: a photo is an image recorded in a camera on light-sensitive film and reproduced on paper coated with light-sensitive chemicals. But even before I could fully formulate that, I realized its folly. After all, Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy were making cameraless photograms in the early 20th century. And plastic or celluloid film itself was a technological innovation introduced in 1889 courtesy of George Eastman—for the first 50 years of the medium's history, practitioners made do with glass plate negatives and direct exposure methods, such as with the daguerreotype. So just what unifies these techniques? Perhaps the answer lies in the content of the images rather than the means of production. To both its benefit and detriment, photography has for most of its history been seen as the medium that promised an honest portrayal of the world. But manipulations and fakes have been part and parcel of photography from the early decades, when ghosts and fairies were duly recorded.

ICP curator Carol Squiers's engagement with the bedeviling question focuses primarily on the 30 years since my photo class, the period in which digital technology has eliminated both film and the darkroom from the practice of many photographers. As Alison Rossiter, one of the artists included here, said recently when talking about the string of technological innovations that make up photography's history, "we get to witness the biggest one, where—whhhpp!—the whole light-sensitive thing was thrown out.”

It is nonetheless useful to approach both the question and the show with a longer history in mind, because truly understanding Squiers's thesis requires more than merely cataloguing the bewildering array of recent innovations. And indeed, her selection of artists provides only a partial view of the ways that artists are addressing the question. Her choices, however subjective, make clear one important point: The changing definition of photography is influenced not just by technology but also by the conventions that successive generations have taken upon themselves. Each convention, in turn, provides a point of rebellion for later photographers. At this time, it seems every facet of the medium is under attack from someone, somewhere.

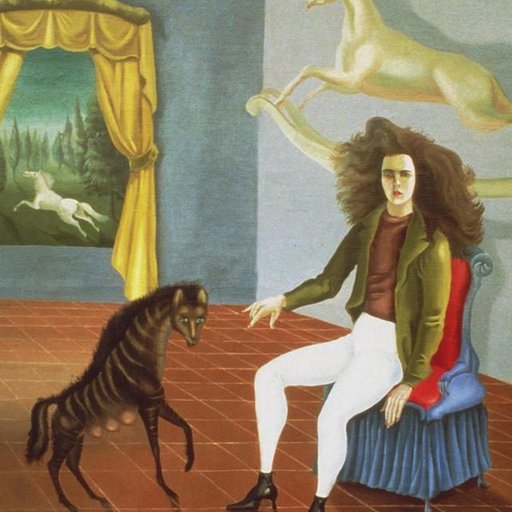

Detail of Mariah Robertson's "154," 2010. © Mariah Robertson, courtesy American Contemporary, New York.

Detail of Mariah Robertson's "154," 2010. © Mariah Robertson, courtesy American Contemporary, New York.

Owen Kydd, for example, is the artist who supplies the video—or "durational photograph," as he has called his work—of the knife. While his camera purposely wavers ever so slightly in the course of the loop, he still presents a single 2-D view of his subject. And, at the same time, he makes the point that no photograph truly captures a single irreducible moment. No matter how fast the shutter speed, a photograph records its subjects over a period of elapsed time. Mariah Robertson, the creator of the colorful abstract scroll, takes on a host of conventions, from where a piece of photographic paper should be cut, to whether a photo should be hung flat against a wall so that it can be taken in in a single view, to whether the subject needs to be recognizable. Longtime innovator James Welling is represented by his large-scale views of Philip Johnson's glass house, captured with strange exposures and reflections and printed in unnatural, saturated hues. Though traditional in technique, they make the viewers question what makes a good photo. Does quality get conflated with the conventional and easily absorbed?

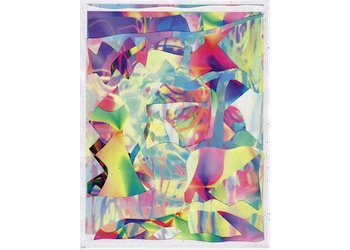

As for the questions of how technology is shaking things up, it's perhaps not surprising that the two youngest artists are the ones who most fully embrace digital tools, their methods superseding Photoshop. Artie Vierkant, still under 30, creates images in the digital realm and then prints, layers, scans, and manipulates them, often repeating the process to create colorful geometric studies that almost appear to be made of light. Travess Smalley, who has called himself a "painter who doesn't paint," digitally cuts up scanned and computer drawn abstractions, then collages them together in trippy, ungrounded works that are indeed painterly. Together with Kate Steciw, whose own digital collages mix figurative and abstract imagery, these artists might be seen as early adopters, embracing the latest technology the field has to offer. They look forward instead of looking back.

Travess Smalley, "Capture Physical Presence #15," 2011. © Travess Smalley, courtesy Higher Pictures, New York.

Travess Smalley, "Capture Physical Presence #15," 2011. © Travess Smalley, courtesy Higher Pictures, New York.

A larger group of artists represented in the show are deeply concerned with photography's past, creating conceptual work that takes that history as its subject. Rossiter has been buying up very old stashes of photo paper and developing them, sometimes to catalogue the traces of lights that snuck in during decades in storage and sometimes to manipulate the outcome by selectively applying chemicals, so the papers reveal bars of black and white. Adam Fuss and Marco Breuer achieve very different results by reviving old materials and methods, from the daguerreotype to the gum bichromate printing process. Liz Deschenes has created the installation of tall, narrow concave black strips, which are not actual mirrors but fully exposed silver-toned paper. The work refers back to zoetropes, a precursor to movies, in which the viewer looked through the narrow vertical slits in a rotating cylinder to watch figures in a succession of images appear to move. In this oversized deconstruction, viewers who walk by see their own ghost-like reflections flitting past, imbuing the works with a mournful quality.

Liz Deschenes, "Untitled (zoetrope) #1" and "Untitled (zoetrope) #2," 2013. © Liz Deschenes, courtesy Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York.

Liz Deschenes, "Untitled (zoetrope) #1" and "Untitled (zoetrope) #2," 2013. © Liz Deschenes, courtesy Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York.

The list of artists goes on, often without adding to the show. Gerhard Richter shows snapshots that he smears with his paint-laden squeegee to mark the end of each day. Richter's influence on our conception of the photograph is worthy of an entire show, but these are not his most penetrating investigations. Marlo Pascual is represented by some rather jokey hybrids of bland images and furniture, which might be seen as 3-D versions of JohnBaldessari's dot pictures. The colored landscapes of David Benjamin Sherry reiterate Welling's point, albeit somewhat less successfully. While Christopher Williams's collages of disassembled old cameras tie in with the theme of the demise of analog photography, what do they really say about the show's title question?

In light of these not terribly compelling inclusions, one wonders about the artists not included. Walead Beshty's lush abstractions are more pleasing than Smalley's and less similar to other works in the show. Curtis Mann's acid-burned images related to current events call into question our expectations for photojournalism, a subject conspicuously absent here and especially relevant given ICP's early mission to promote it. Christopher Bucklow, who uses traditional techniques, such as the pinhole camera, to create works that read as extremely contemporary, would have provided a voice calling into question the medium's impulse to embrace the new.

These complaints are more than quibbles, but the show holds interest for its plainspoken address of the basic question hovering over all of photography today. Hopefully ICP and another institution can follow up with more acute examinations of this unanswerable riddle.