Art as Therapy

By Alain de Botton and John Armstrong

Phaidon

240 pages

$39.95

THE THESIS

The initial argument presented here by cultural critic and pop philosopher Alain de Botton, writing with the art historian John Armstrong, is as straightforward as its title. The eternal purpose of art has been obscured by the art establishment, and true art lovers should take it upon themselves to reclaim art for their own use.

"The saying 'art for art's sake' specifically rejects the idea that art might be for the sake of anything in particular," the authors lament in the introduction. "What if art has a purpose that can be defined and discussed in plain terms?… This book proposes that art…is a therapeutic medium that can help guide, exhort, and console its viewers, enabling them to become better versions of themselves."

Unsurprisingly, more than a few in the art world have taken exception to the book, which critiques the way historical analysis has overtaken emotional connection as the means by which most schools and museums present art. And one can imagine that a good many contemporary artists would prefer to have their work not reduced to the level of self-help tool. Yet, in a cultural landscape in which fine art is often marginalized as elitist, it's easy to see the popular appeal of an approach to art that gives viewers a clear means to appreciate pictures that doesn't require a masters degree in "isms." In fact, this book's thesis is so seductive that the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is experimenting with wall texts written by de Botton and Armstrong, and the Art Gallery of Ontario is mounting an entire show that rehangs works from the collection in a way that emphasizes their therapeutic value.

WHY WE SHOULD CARE

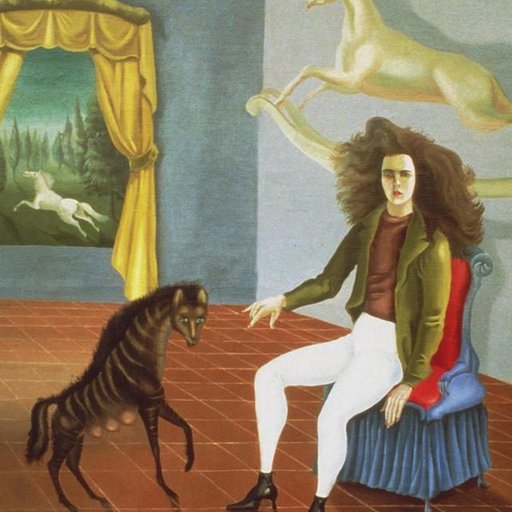

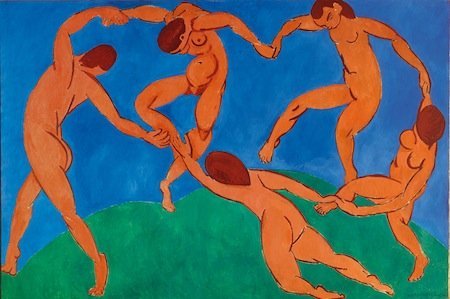

Matisse's Dance (II) is "What hope might look like."

The book's first section clearly lays out how great art can aid even those completely uninitiated in art history. "The seven functions of art" are enumerated in chapters on remembering, hope, sorrow, rebalancing, self-understanding, growth, and appreciation. Under each heading, the authors explain both the broad principal and the specific application through works ranging from paintings by Johannes Vermeer and Caspar David Friedrich to photos by Eve Arnold and Nan Goldin. Accompanied by generous illustrations, these short analyses of the artworks are mostly persuasive, and one can easily bring to mind other works that might aid those searching to bring hope or balance into their lives.

In the chapter on sorrow, for example, de Botton observes that one of Richard Serra's massive vertical slabs of steel "does not deny our troubles; it doesn't tell us to cheer up. It tells us that Sorrow is written into the contract of life. The large scale and overtly monumental character of the work constitute a declaration of the normality of sorrow." Never mind that Serra may not be fully on board—it is a persuasive, if not fully rounded, interpretation.

It's less clear why the authors limited themselves to these specific functions, but that is not much of a criticism. The fact that one could imagine artworks also put to use to nurture our capacity for tolerance or courage should be understood as an endorsement of expanding their core idea.

WHY WE MIGHT BE SKEPTICAL

Caspar David Friedrich's Rocky Reef on the Sea Shore conveys that life's difficulties

are "part of the structure of the universe."

Unfortunately, de Botton's bid for a more purposeful engagement with art gets us only to page 63 (although the theory pops up occasionally in later sections, where he explains how artworks might teach us patience in love and a greater appreciation of nature). For the next 170 or so pages, he engages a range of questions touching on everything from aesthetics to economics that have tripped up loftier thinkers. Kernels of good ideas surface in these meandering essays, but they are swamped amid logical inconsistencies and an apparently boundless confidence that de Botton knows best.

In a chapter titled "What Counts as Good Art?" the author implies he does not really like Caravaggio's Judith Beheading Holofernes. From that subjective experience de Botton leaps to the conclusion that the masterpiece's canonical prestige in the filed of art history may be misplaced because it lacks the "power to touch one's soul."

In a section on the various ways in which money intersects with art, the author puts out a call for enlightened investment in which he takes the the real estate mogul and Islamic art megacollector Nasser David Khalili to task. "Would it not have been better for all of us if, rather than making money through selling Scotland's hideous Cameron Toll shopping center and giving away a portion of the cash to the Hermitage Museum, Mr. Khalili had simply made slightly less money, but done so by building beautiful shops and houses that could have enhanced the tenor of everyday life across the modern world?"

WHY WE SHOULD RUN AWAY SCREAMING

For de Botton, Eve Arnold's Divorce in Moscow expresses "A reason to say sorry."

Given de Botton's willingness to let his taste overrule an entire academic field and dictate the actions of private individuals, perhaps the reader should not be surprised to come upon the chapter near the end of the book headed "A Defence of Censorship." Over the course of eight pages he moves from the idea that we need to restrict advertisements in public space to a condemnation of television shows that "constitute an obstacle to self-knowledge" to a declaration that because freedom has been achieved in democratic societies "We are now faced with the task not of liberation, but of organization." If de Botton's earnest self-help text were not so devoid of humor up to this point, the reader might laugh at his ironic observation that "if the advocate of censorship offer their own services as the arbiter of what should be allowed in the public realm, they inevitably sound unhinged and egotistical." Indeed.