Though technologies and fashions may develop over the years, the human body is supposed to remain constant, a basic form we can all more or less agree on. In the tumult of the 20th century, however, the human figure became the site of immense change as artists struggled to represent our fragile bodies in a time of unprecedented advancements and horrors. These seven sculptures from the past century, each excerpted from Phaidon’s The Art Book, show just a few of the ways artists reimagined what the human figure could be.

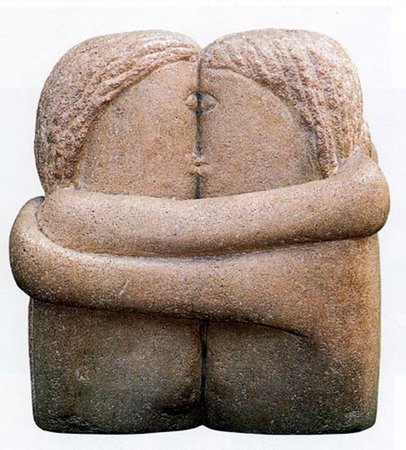

CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI

The Kiss, 1907

Tightly entwined, two lovers embrace in a passionate kiss. The elemental power of this work is expressed by the bulk of the stone from which the forms are only sketchily emerging, as if roused from a timeless slumber. Brancusi reduced his sculptures to their most basic, most abstract, lending them a primordial vitality. Eschewing all surface decoration, nothing but pure form remains. Brancusi had an immense effect on twentieth-century sculpture and abstract art in general. The simple grandeur of his works evokes a sense of freedom and strength. In 1904 he walked from Romania (the country of his birth) to Paris, a feat which gained him widespread admiration. His celebrity was further fuelled by the law case he brought against US Customs, who wanted to charge duty on an imported bronze sculpture which they considered as nothing more than raw material, thus liable for tax.

ARISTIDE MAILLOL

The Three Nymphs, 1930-37

Originally conceived as a classic representation of the mythic Three Graces, this bronze statue has great solidity and weightiness in its smooth, rounded curves and restrained movements. Although Maillol’s concept changed while he was working on the preparatory plaster casts, the mirroring effect of the three nudes, which gives the impression of three views of the same girl, is also typical of Classical representations of the Three Graces. Maillol did not adopt the rough surfaces, fluid shapes and intense energy of his contemporary, Auguste Rodin. He was more interested in calm than in drama, in timeless serenity than in fleeting expressions and emotions, seeking the eternal rather than the momentary. After spending several years designing tapestries, in the second half of his life he concentrated almost exclusively on sculpting the female nude, and revived the Classical ideas of Greece in the fifth century BC, in which figures had a fixed and monumental quality.

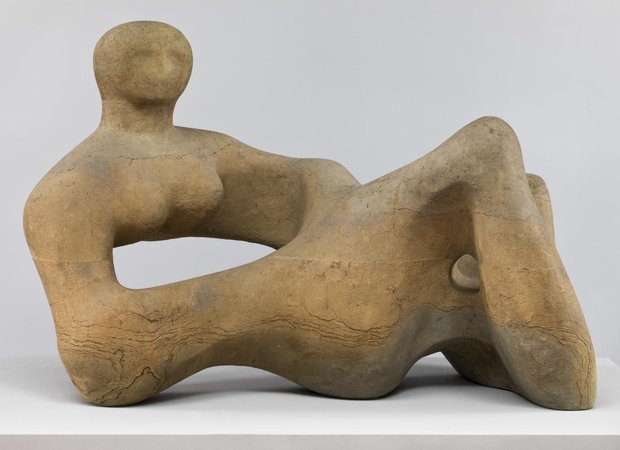

HENRY MOORE

Recumbent Figure, 1938

Monumental and almost primeval, this carved statue seems to have been created more by the forces of nature than by man. Semi-abstract in form, its smooth and rounded outlines suggest the work of the elements, while at the same time evoking the soft curves and flowing outlines of a female body. Inspired by the vitality of ancient and primitive sculpture, Moore revived the tradition of direct carving into stone or wood. In so doing he emphasized the natural textures of his material, and in his massive works he consciously reflected the contours and qualities of landscape and rock. As a result, the simple, solid shapes of his sculptures have a powerfully brooding presence. One of the distinguishing hallmarks of his figures or groups was that they were often pierced. Moore’s works are frequently displayed in the open air, and several of his commissions stand outside major buildings in North America and Europe.

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Walking Man, 1961

This emaciated, monumental figure with a roughly pitted and textured surface is hauntingly powerful. Through its unnatural, elongated shape, the sculpture is intended to signify solitude and the absolute separation between ourselves and our fellow man. It also underlines our fragility and the ephemeral nature of human existence. In contrast to other sculptors, Giacometti did not start with a large mass of material which he chipped and chiseled to find a form hidden within. His technique was to start with a metal skeleton and add clay to it, which he would then cast. Giacometti’s singular style of expression kept him apart from the post-Second World War styles of painting and sculpture. Born in Switzerland, Giacometti settled in Paris in 1922. His paintings and drawings reflect the same restless, nervous quality as his sculptures. Made up of sharp, energetic strokes of paint they have a stark and haunting beauty.

DAME ELISABETH FRINK

Goggle Head, 1969

Fascinating and frightening, this menacing head, its identity hidden by shiny goggles, suggests deliberate violence. It evokes images of sophisticated modern-day criminals, dictators’ henchmen, or even Hell’s Angels motorbike riders. Smooth in outline, it is executed in the shape of a Classical bust yet possesses a fearsome and disturbing quality. Random scratches, like those inflicted by an animal, cover its surface. Frink was one of the first British sculptors to create works in a Neo-Expressionist style, portraying her own feelings about the complex nature of humankind, its strengths and its vulnerabilities. She is equally well known for her sculptures of horses and dogs, which illustrate the sensitivity of her response to nature. Her last major commission was an impressive and dramatic figure of The Risen Christ, a bronze sculpture almost 4 metres (13 feet) high that is now fixed to the façade of Liverpool Cathedral.

LOUISE BOURGEOIS

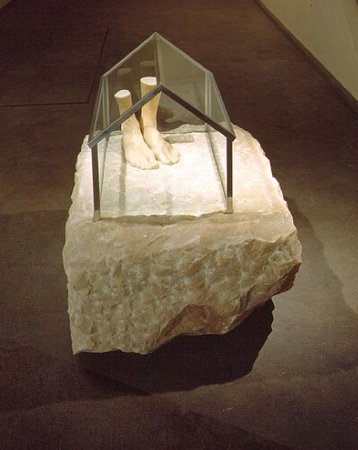

Here I Am, Here I Stay, 1990

Encased within a glass casket, a pair of truncated human feet are firmly placed on a roughly hewn block of marble. Perhaps alluding to the triumphant order man has created out of the disordered chaos of nature, the elemental qualities of the material – marble, glass, metal – evoke the timeless world articulated by human endeavor. Great attention has been paid to the sensual surfaces, ranging from the roughness of the stone hewn from the earth to the smoothness of the man-made glass. Bourgeois’ work is frequently suggestive of the human form, often in a remote, abstracted context. The dynamic tensions of opposing materials and finishes raise provocative responses to the physical presence within the natural environment. Bourgeois moved to New York from Paris in 1938 where she had worked with the Surrealists. Initially a painter and engraver, she turned to sculpture in the late 1940s.

CHARLES RAY

Family Romance, 1993

Hand in hand stand a father and mother, along with their two children, a boy and a girl – the archetypal nuclear family. Bold in their nakedness, the artist has crafted each figure with a high degree of realism down to each individual hair. However, in contrast to this anatomical accuracy we are instantly aware of a strangeness of scale. In choosing to standardize the height of each figure to just less than 135 cm (4ft 5in), the adults have been necessarily reduced in size, while the two children are noticeably enlarged. The result is unnerving. The children have taken on a menacing presence, their physical frames more imposing than those of their parents. Based in Los Angeles, Ray has produced works across a wide range of media including photography, film, sculpture and installations. He was inspired early in his career by the work of Anthony Caro.