“Informality reigns in SoHo, the new art gallery neighborhood below Houston Street, and that extends to the way art is viewed and vended.” In 1970, the New York Times ran “Art: A Downtown Scene” and many other stories like it, hailing SoHo as the new home of the avant-garde. The area became a haven for artists in the late 1960s after the Lower Manhattan Expressway project fell through, which would have cleared the area to make way for two highways.

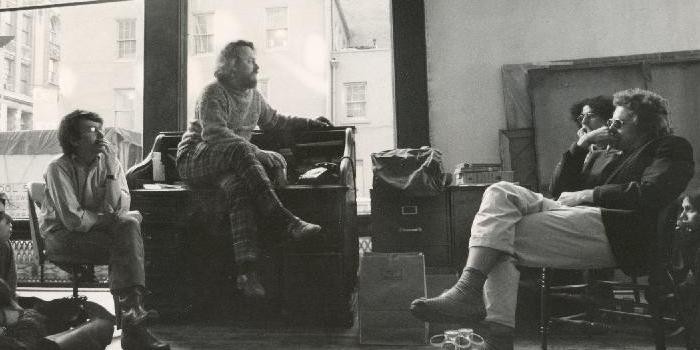

Donald Judd at 101 Spring Street in 1970. Photo by Paul Katz, Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives.

A front page Village Voice story in November of 1969 describes how artists began (illegally) filling the neighborhood's large, empty industrial spaces, even though they weren't zoned for residential use, with James Rosenquist and Paula Cooper Gallery being name-checked as pioneers of the area. Cooper’s gallery often gets cited as the first in SoHo: she relocated to Prince Street from uptown in 1969, and by 1973, there were 33 galleries. With cheap rents, huge spaces, and great light, the loft clearly became attractive to artists, many of whom could not afford to keep both a studio and an apartment—so they started living where they worked. SoHo was home to about 2,000 artists by the early '70s, many of whom had to go as far as Chelsea to get basic groceries and faced police shakedowns as part of failed efforts to clear them out. In 1971, Gordon Matta-Clark and Carol Goodden founded the conceptual art project/restaurant FOOD to provide a much needed meeting ground for the neighborhood's artists— a project that was the subject of a tribute at Frieze New York this year .

101 Spring Street in 1972. Photo by Paul Katz, Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives

The early artist’s era of SoHo is clearly having a moment: Donald Judd’s building at 101 Spring opens to the public for tours today in honor of the late artist’s birthday. Judd, who bought the building in 1968, famously lived among works by Claes Oldenburg , Dan Flavin , Ad Reinhardt, Carl Andre, and many others, sometimes hosting private concerts and events for friends such as Philip Glass. His precise arrangements of art and furniture have been carefully restored as part of a three-year project, which also involved extensively replacing the cast-iron façade for which the SoHo neighborhood became famous.

101 Spring Street post-restoration, featuring works by Judd, John Chamberlain, Lucas Samaras, and Dan Flavin. Photo by Josh White.

The story of SoHo—which was transformed from a bohemian artist’s enclave to one of the most expensive zip codes in the country—has remained significant not only because of the now-iconic artworks it helped produce: in just a few decades, the area has become a retail and restaurant capital with upscale homes and hotels. The “SoHo Effect” demonstrates how artists and art can transform neighborhoods and then economies on a grand scale.