"The Pictures Generation" is as elusive as any label attached to a group of contemporary artists. As it is often used, the phrase refers to a range of painters and photographers active during the 1970s and ‘80s whose work made use of images appropriated from mass culture. With that understanding, it’s easy to conjure up some of the hottest names in the last half-century of American art—from Cindy Sherman to Richard Prince to Barbara Kruger. But none of those artists were part of the original "Pictures" artists, who were brought together for a show with that name at the nonprofit Artists Spacein 1977.

Curated by critic Douglas Crimp, the show featured only Troy Brauntuch, Sherrie Levine, Jack Goldstein, Robert Longo, and Philip Smith. Since then, the legend of the show has grown in tandem with the importance of appropriation in contemporary art, so that both Crimp's underlying thesis and the artists encompassed by it have been expanded upon and rendered murky. By 2009, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art staged its monumental exhibition "The Pictures Generation," curated by Douglas Eklund, one of the original members didn’t even make the cut.

So how is the rubric understood today? Here is a guide to the Pictures Generation, its influences, and the important ideas it left behind.

FROM MINIMALIST BEGINNINGS

Andy Warhol's Electric Chair (1972)

Andy Warhol's Electric Chair (1972)

The members of the Pictures Generation grew up during a decade when art was radically changing. During the ‘60s, the art world saw the rise of diverse and divergent movements from Pop, to Conceptual art, and finally, to Minimalism. Each had its own agenda and style, but all three movements played a part in diminishing the significance of the boundaries between painting, sculpture, photography, and performance.

As children of the ‘60s, the Pictures artists were also exposed to the rise of consumerism that both drove emerging mass media like television and was celebrated in it. It wouldn’t be hard to say that an obsession with images was deeply embedded before they even graduated high school. Combined with the political and social unrest that brought the decade to a close, and its artistic upheaval, this newly immersive visual culture gave the artists who would form the Pictures Generation a unique set of formative experiences.

THE FIRST "PICTURES" SHOW

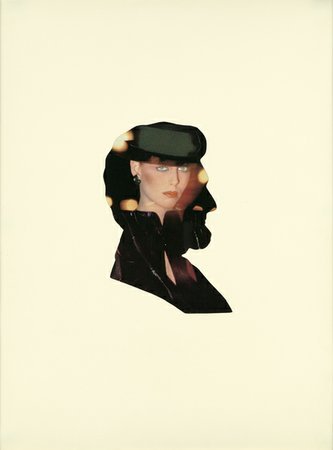

Sherrie Levine's Untitled (President: 4) (1979)

Sherrie Levine's Untitled (President: 4) (1979)

In 1977, Douglas Crimp brought together five artists in Artists Space, a small alternative gallery in Tribeca, for a show called "Pictures." The show drew attention because of Artists Space’s radical reputation, but it was the artists themselves who caused the show to go down in art history. They were grappling with the idea of "re-presentation, not representation," as Crimp put it in his essay (also titled "Pictures"), which appeared in October two years later.

Re-presentation involved the appropriation of images, presenting them in new ways, and then having viewers think about the new meanings of these images. As Eklund put it in his catalogue for the Metrolpolitan exhibition, after Minimalism became an endgame for art, re-presentation appeared to some artists to be the only option left.

PHOTOGRAPHS OF PHOTOGRAPHS

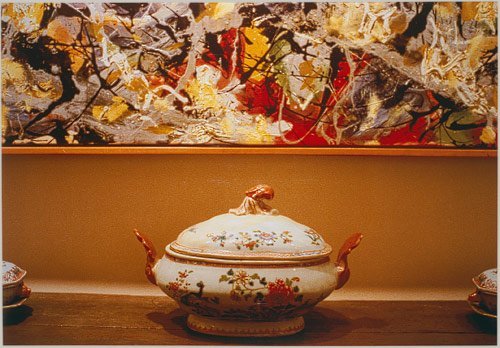

Louise Lawler's Pollock and Tureen: Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Connecticut (1984)

Louise Lawler's Pollock and Tureen: Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Connecticut (1984)

For the original "Pictures" artists and even more so for those who came, photography became an important medium for experimentation. It’s not surprising, considering their interest in mass-reproduced images, often taken from advertisements. Even when grappling with art from earlier times, the general public was probably more familiar with the reproduced image than the original image. With this in mind, Sherrie Levine’s re-photography of Edward Weston’s photographs for her After Edward Weston series becomes a question of originality. It asks about the difference between originals and copies. To some observers it threatened to become the final nail in modernism’s coffin by commodifying modernist art.

TURNING THE LIE BACK ON ITSELF

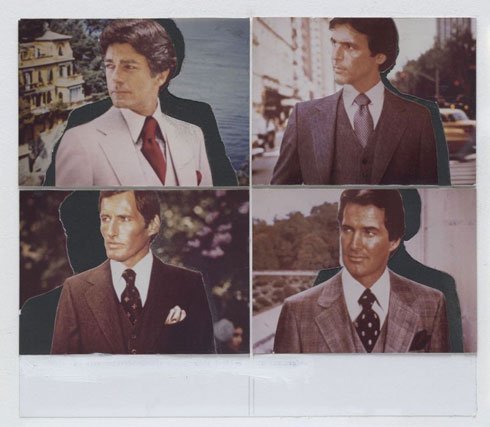

Richard Prince's Untitled (1977)

Richard Prince's Untitled (1977)

For many of the "Pictures" artists a central tenet was that it is up to the viewer to complete the images by bringing their own experiences and ideas to a work. In some ways, it was an idea derived from the writings of French philosopher Roland Barthes, who theorized that individual authorship was dead, and that society’s ideas gave things their meaning.

The idea of viewer completion was realized in various ways. For some artists, viewer completion became political. In Laurie Simmons’s art, for example, female dolls are photographed in various domestic settings to understand how certain images can inform certain gender roles. But in other cases, viewer completion became a more theoretical activity. For Conceptual photographer Sarah Charlesworth, the point was to present an image and let the viewer find possible referents. As Richard Prince put it, his re-photographed advertisements “turn the lie back on itself” by relying on viewers to understand that they had seen the same images a million times over, and that these images were a fiction.

"PICTURES" FOR A NEW GENERATION

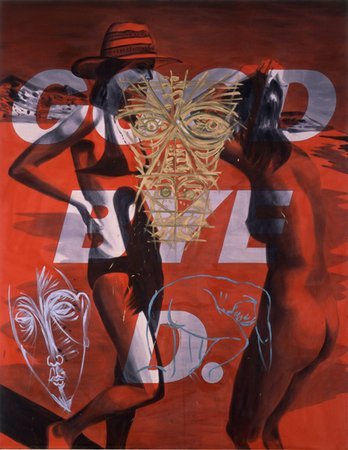

David Salle's Good Bye D. (1982)

David Salle's Good Bye D. (1982)

It wasn’t until 2009 that the "Pictures" artists got the museum show they always deserved. In a then-rare move for the Metropolitan, "The Pictures Generation, 1974-1984" was given a sizable amount of space for an exhibition of contemporary art, and its catalogue was pretty hefty, too. Of course, as is always the case with exhibitions, some art history got rewritten. Only four of the five original Pictures artists made it into the exhibition—Philip Smith’s work was notably absent. (In response, Smith wrote a fiery letter to Art in America and claimed that Eklund never even considered his work.) At the same time, Eklund added a few artists to the show, too. David Salle, who had typically been regarded as a conceptual influence on the "Pictures" artists, was exhibited alongside the work of Levine and Sherman, and the generation was extended to include artists' work through 1984.

Today, the influence of the Pictures artists is still being evaluated. It wasn’t until this year that Jack Goldstein, an original Pictures artist, received a posthumous solo museum show (at the Jewish Museum). Even with all Levine and Longo’s success, Smith and Brauntuch still await their own solo museum shows.