Recently named one of our "10 Artists to Watch This April," Tbilisi-born, Berlin-based sculptor Thea Djordjadze is on deck for a packed spring/summer season with a solo show, Projects 103: Thea Djordjadze, already in full swing at MoMA PS1 and a gallery show at her hometown’s Sprüth Magers during Berlin Gallery Weekend (April 30 - June 25). Alongside such peers as Cao Fei, Rodney McMillian, and Lionel Maunz, Djordjadze continues her exploration of specter-like minimalism, fragility, and tactility with a site-specific installation at MoMA PS1.

In this excerpt from Creamier: Contemporary Art in Culture, Phaidon’s acclaimed compendium of curators' musings on major artists, Brussels-based curator and critic Elena Filipovic unveils how the Georgian sculptor is disrupting and remolding Modernist sculpture with the most breathtaking gestures.

A critic once compared Thea Djordjadze’s sculpture to “calcified doves’ wings,” a description that captures the frail beauty but also the eerie embodiedness of so many of her emanations. I say “emanations” because it seems the most appropriate word for the plaster, clay, and papier-mâché forms that appear to emerge organically from the Georgian sculptor’s hands. The strangely misshapen objects, at once modest, awkward, and commanding (that is their paradox), are as much concrete forms in their own right as they are evidence of the gesture and touch that made them: unapologetically showing the stuff of their own making, each piece feels haunted by the ghost of the action as well as of the hands that constructed them.

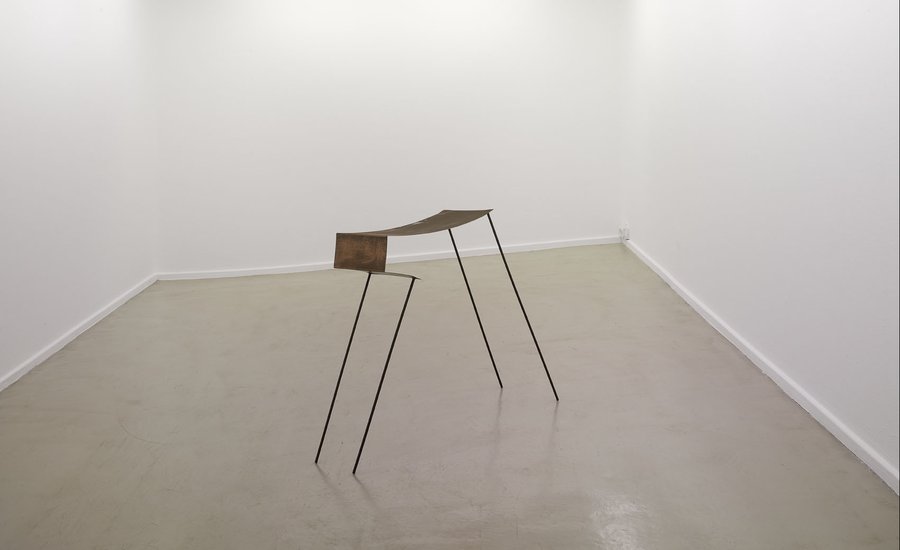

All men are equal but some are more equal, than others (Orwell), 2008

All men are equal but some are more equal, than others (Orwell), 2008

At times powdered with plaster dust, sitting on salt crystals strewn across the floor, or positioned on traditional rugs made by nomadic tribes in Uzbekistan or Anatolia, Djordjadze’s objects seem charged, like props for an archaic ritual, incomprehensible, and mysterious. They have been compared to archaeological troves or fossils, and this is in part because they seem decidedly not of our time. Yet where to locate them temporally, historically? Modernist architecture and design is often quietly evoked in her work, but Djordjadze immediately deforms the modernist ideal, abutting its rigidity, its cult of perfection or form-follows-function rationality, with its opposite.

Her sculptures sometimes channel geometric lines and a spare architectonics yet, placed next to or around these are craggy, folded forms that are infinitely flawed and wholly human; they sit like vestiges of the past and future, as in All men are equal but some are more equal, than others (Orwell) or Archäology Politik Politik Archäology … (both 2008). Even though modernism was self-consciously aimed at the transcendent, Djordjadze complicates this notion, since her objects seem to surpass this world and remain decidedly tied to it. It is no coincidence that so many of her pieces lie low to the ground, as if bound by an invisible umbilical cord to the earth beneath: the result propels the viewer to lower his or her body, giving a double sense to her particular base materialism.

Deaf and Dumb Universe (Raumgerüst), 2008

Deaf and Dumb Universe (Raumgerüst), 2008

For Deaf and Dumb Universe (Raumgerüst) (2008), Djordjadze smeared a mix of plaster dust and water onto one window panel of Mies van der Rohe’s iconic exercise in absolute symmetry, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. This messy disruption of the clean modernist minimalism of the site suggests another crucial aspect of her practice: her emphasis on the means of viewing the artwork. In her hands, pedestals become sculpture, perilously encroaching on the status of the objects that they are meant to serve and present. One cannot help but think of Brancusi’s radical approach to the plinth, which transformed what had been its secondary and functional role of merely supporting sculpture or constructing a viewing distance for it.

Djordjadze emerges from this lineage, extending the idea of the sculpture’s base to make it integral and expansive. But if her presentational structures are of the same conceptual order as the objects that she has placed on or near them, rendering ambiguous the boundary between each, she is neither producing pedestals as autonomous objects nor objects that seek out an autonomy distinct from their context. Rather, it is the tension between the two that her work defiantly seeks.