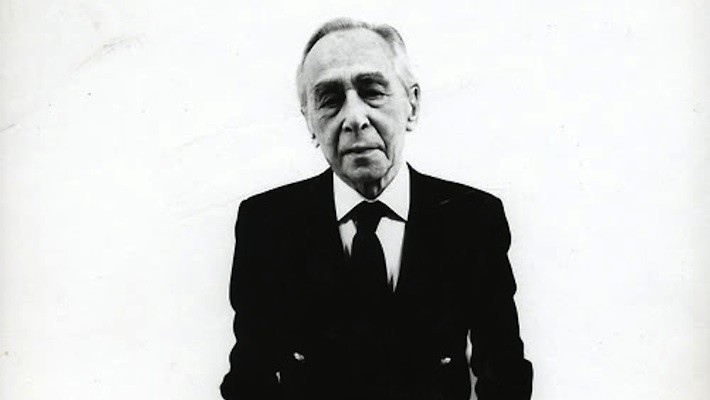

Forget everything you learned in art history class: the most influential figure in 20th-century American art was not Jackson Pollock or Andy Warhol. It was the Manhattan art dealer Leo Castelli. A genteel titan who did more than anyone to shape the art world as we know it today, Castelli was born in 1907 in Trieste with the Jewish given name of Leo Krausz and took his time finding his way to fame—he was nearly 50 years old when he opened the Castelli Gallery on East 77th Street in 1957. By that time, however, he was ready.

Epitomizing art worldliness before there truly was a global art world (he spoke five languages), Castelli ran his shop until his passing in 1999, and over those four decades he debuted to the world an astonishing range of artists: Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Donald Judd, Cy Twombly, Richard Serra, Joseph Kosuth, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Richard Artschwager, Dan Flavin, Bruce Nauman, and Ed Ruscha are just a few.

He was unusually well-equipped for his role. A bon vivant and thrice-married ladies' man (his first wife, the legendary dealer Ileana Schapira, later Sonnabend, introduced him to the art world in Paris), Castelli earned his U.S. citizenship by working for the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor to the CIA) during World War II, and his skills in diplomacy and information-gathering both helped his career immensely. As he once told the New Yorker's Calvin Tompkins, "You have to have a good eye, but also a good ear." He also had a silver tongue. (Once, his friend Willem de Kooning joked that “You could give that son of a bitch two beer cans and he could sell them"; Johns took the challenge seriously, gave him a sculpture of two Ballentines beer cans, and Castelli sold them.)

In some ways, Castelli operated his gallery in a manner alien to the megagalleries of today: for one thing, he was predominantly interested in artists he could nurture from the beginning; for another, he claimed he never played the secondary market. However, there are a staggering number of areas in which his influence is still felt today. Here are some of them.

HE GAVE ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM ITS DUE

Half a decade before opening his eponymous gallery, Castelli—who was a member of the famous Club, the heady discussion group where the leading Abstract Expressionists of the day debated artistic ideas—concluded that the Ab Exers had not been sufficiently embraced by American collectors and institutions and decided to organize a show promoting their work. The result, taking place in 1951 in a basement at 60 East 9th Street, was simply called the "9th Street Show" and featured work by about 60 artists including de Kooning, Pollock, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan, Philip Guston, Hans Hofmann, and many others, constituting a veritable "who's who" of the movement. It was an enormous success, bringing droves of visitors down to the heart of New York's avant-garde (then the East Village) and broadcasting the dynamism of AbEx to the world.

HE CLOSED THE DOOR ON ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM

In 1958, Castelli paid a studio visit to Robert Rauschenberg and, after an inconvenience cropped up (some say they needed assistance moving an artwork, others say they needed ice for drinks), the artist suggested they ask his downstairs neighbor for help. When that neighbor turned out to be Jasper Johns, Castelli—who had been already intrigued by the artist after seeing one of his green target paintings at the Jewish Museum—was staggered by the paintings of maps and targets on view in his studio and immediately asked him to show at his gallery.

Later, upon the encouragement of his wife, Ileana Sonnabend, Castelli took on Rauschenberg as well, and those two artists together went on to usher American art away from Abstract Expressionism and toward Pop art, Minimalism, and Conceptual art. Castelli himself regarded the show that sprang from his impromptu visit with Johns as "the death knell, actually, [of] the Abstract Expressionists… [and] the turning point in American painting."

HE MADE AMERICAN ART THE ENVY OF THE WORLD

Until the 1950s, the course of post-industrial art history was guided by European dealers like Lord Duveen and D.H. Kahnweiler, who crafted markets for everything from Renaissance art to Cubism—and often sold them to American buyers desperate for a veneer of old-world culture. Castelli changed all that. Early on, he was the first (he claims) to "mix American with European and so forth classics… [as] a ploy to attract collectors," bringing U.S. art on par with the refined works from across the pond. The "9th Street Show" then broadcast America's artistic achievements around the world, and Castelli subsequently did everything he could to enhance the reputation of the country's art abroad.

The turning point came in 1964, when Rauschenberg became the first American artist to win the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale—an achievement that stunned the international art community and helped make American art an international status symbol and object of desire.

The irony, of course, is this change was so largely brought about by a man who was a consummate European himself—Tom Wolfe once called Castelli "the eternal Continental diplomat"—and who credited his own artistic vision to the influence of a Frenchman. "The key figure in my gallery is somebody that I never showed, and that was Marcel Duchamp,” Castelli said. “Painters who are not influenced by Duchamp just don’t belong here.”

HE CREATED THE FIRST MEGAGALLERY

If today is very much the era of the megagallery, with dealers opening colossal spaces to lure ambitious artists and impress collectors, we have Castelli to blame. Opening his first New York gallery on the Upper East Side at a time when there were very few dealers operating out of the city, he later helped establish SoHo as a thriving art district in the 1980s when he opened a humongous (at least by those days' standards) space on Greene Street. The scale of that gallery inspired other dealers, which was one of the reasons that so much of the art market relocated to the expansive warehouses of Chelsea.

HE KEPT HIS ARTISTS ON RETAINER

Whereas other dealers supported their artists only through proceeds from the sale of their work, Castelli was known for providing his artists with a regular stipend regardless of whether their work sold or not—a generous strategy that allowed him to nurture artists until they grew fashionable, and to help others survive dips in demand. When the young Richard Serra joined the gallery in 1967, he was moved when Castelli assured him of three years of monthly paychecks without expecting anything immediately in return ("It was like getting a Rockefeller grant," Serra said). Castelli explained his approach this way: "I never tried to pick painters to make a lot of money. If artists have had no success with me in the first 15 years, they go on to the next 15, as long as I like their work." Today this practice has been adopted by many other galleries.

HE CREATED THE FIRST GALLERY SATELLITES

While Castelli never followed up his success in New York by opening another gallery of his own outside the city, he did prefigure the current vogue for international expansion by striking arrangements with dealers across the country and around the world to allow them to sell work by his artists. Among the dealers he worked with are Dallas's Janie Lee, Toronto's David Mirvish, and Los Angeles's Margo Leavin.

HE HELPED LAUNCH LARRY GAGOSIAN AND JEFFREY DEITCH

Another dealer that Castelli worked with in L.A. was a young former poster salesman named Larry Gagosian, who met the dealer through the photographer Ralph Gibson and went on to work with him closely. In a recent interview, Gagosian credited the dealer with such kindnesses as introducing him to Condé Nast publisher and renowned collector Si Newhouse and with "show[ing] me that you could have a lot of fun being a dealer…. that you could have a business as serious as Leo Castelli's and still have a wonderful life." (Gagosian added, "The other thing he taught me was not to give too many interviews.")

Another person Castelli helped along was Jeffrey Deitch, who helped him sell off most of his defunct print business, Castelli Graphics, for $2 million in the '80s—and whom he rewarded by giving the aspiring dealer his entire professional mailing list, a gesture Deitch has called "unimaginable."

HE LEFT HIS BLUEPRINT BEHIND

After Castelli's death, his family donated his papers to the Archives of American Art—a trove that includes sales records for every piece the gallery sold over its 42-year existence and correspondence with his artists and clients. This rich historical record, which today amounts to over 400 feet of chronologically filed documents, has been made available to anyone curious to delve through it. For anyone interested in becoming a dealer, or collector, of historical consequence, that might not be such a bad idea.

In this collection, we pay tribute to Leo Castelli's influence by presenting works by artists who have shown at his fabled gallery.