This year marks the 70th anniversary of Polaroid’s first black-and-white prints becoming commercially available (previously Polaroid film only created sepia-tinted images). From photographers’ very first experiments, the actual physicality of the Polaroid was an important part of the process. At that point, Edwin H. Land’s invention was still using the peel-apart film (a colour version was introduced in 1963), with non-peel-apart prints arriving in 1972. While each of these innovations signified progress of sorts, the very flexibility of the different iterations of Polaroid – not just in film type, but also size – gave these formats a long afterlife, as photographers manipulated and experimented with them to shape the end results. The best way to consider the Polaroid is that before it's exposed and developed, each individual, chemical-filled picture is a miniature, self-contained dark room, with all the options that entails. Many artists from the Artspace archive have worked with the medium in radically different ways – here’s our edit of the best.

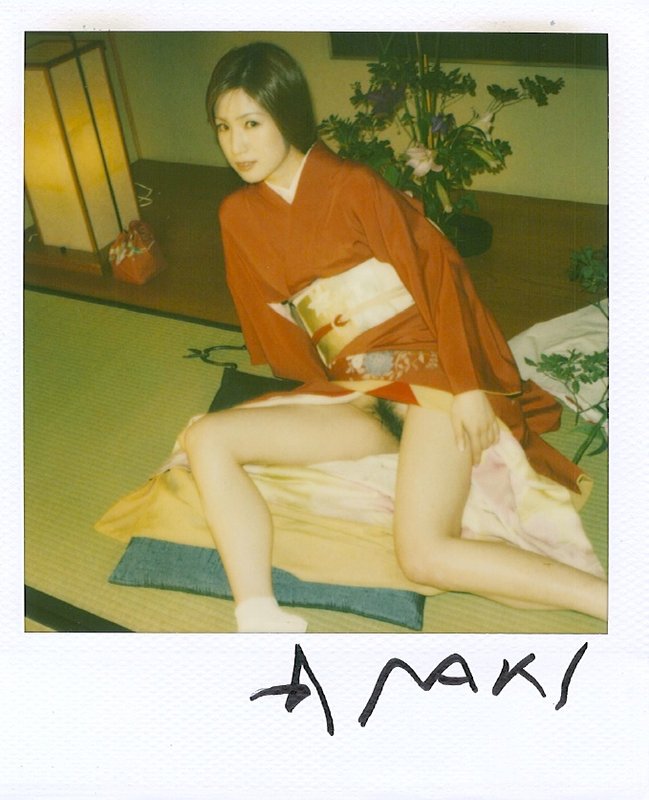

Noboyushi Araki – Untitled (72-025) (2018)

Nobuyoshi Araki is a prolific if problematic photographer. From his earliest work – 1971’s Un Voyage Sentimental, in which he displayed all the details (from the mundane to the intimate) of his honeymoon with his wife, he has worked towards removing the layers of distance and artifice around photographic shoots, giving them – literally and figuratively – the utmost reality and immediacy. Critics often focus on the nudity and sexualisation in his most controversial pictures, but Araki has been equally unflinching when looking at his wife’s terminal illness, his pet cat, or the unappetizing food on the plate before him. In Araki’s world, all are flattened down together, the shapes and colours of life presented to the viewer with any moral value or guidance removed. Given this, the Polaroid is a perfect medium for his work – more intimate, more immediate, more ‘real’ than a standard portrait format.

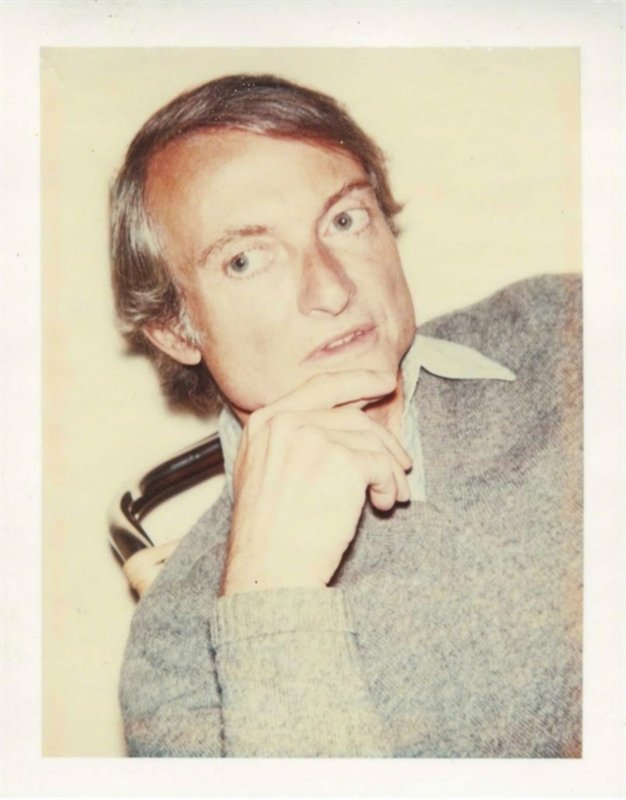

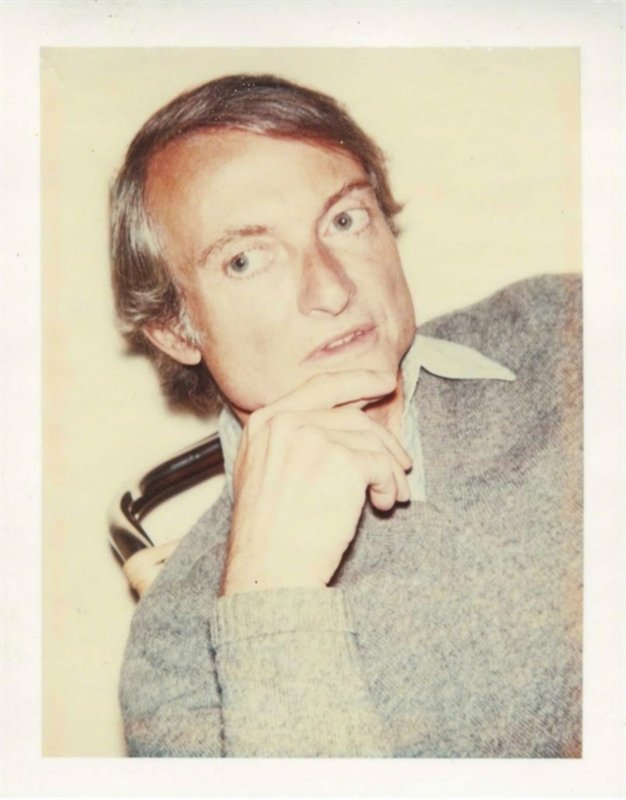

Andy Warhol – Roy Lichtenstein (1975)

The relationship between Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein was complex, a friendship marked as much by competitive rivalry as by warmth. While they shared a representative – the renowned Leo Castelli Gallery – Warhol’s rivalry was reportedly ramped up after a show of Lichtenstein’s in 1961 where he observed that Lichtenstein had painted Mickey Mouse, thus beating Warhol to the subject. The painting in question, Look Mickey, is a hugely significant one in Lichtenstein’s career, being one of his first non-Expressionist works and a bridge to his later Pop Art work. Art critic Alice Goldfarb Marquis claimed that the artist claimed he was inspired by his young son who showed him the Disney cartoon and said ‘I bet you can’t paint as good as that.’

This portrait was taken by Warhol 14 years later, using the Polaroid Big Shot. Released in 1971, this was one of Polaroid’s strangest cameras – looking like a horizontal periscope, it shot in portrait mode, had an integrated flash unit and diffuser, and a fixed focal length of about a meter (so the photographer had to physically move themselves backwards and forwards to get the subject in focus). It was discontinued just two years later, but Warhol continued using it until his death. ‘Everybody looks alike and acts alike, and we’re getting more and more that way,’ Warhol said – and the countless Polaroids that he took of the people he encountered, with their uniform format, framing, light and tone, reinforced that. The Polaroid was the perfect camera for an artist who saw repetition and the mundane as art forms in themselves.

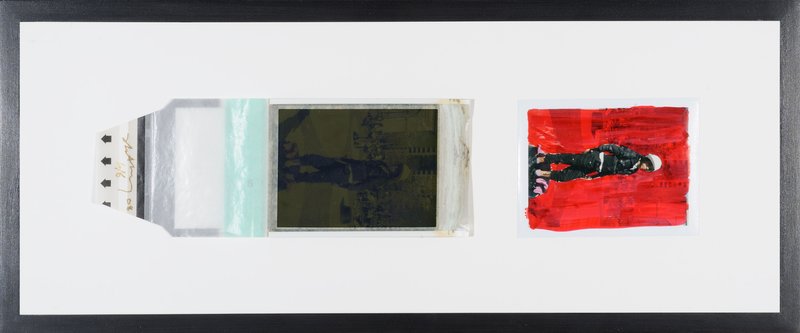

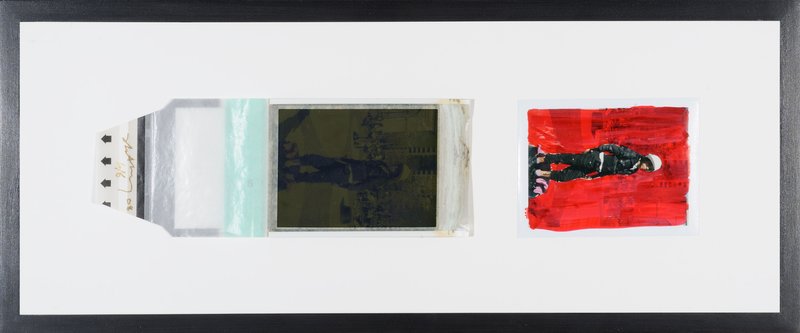

Slater Bradley – Soundless pounding of accelerating dreams, 2008

Slater Bradley was born in San Francisco but currently lives and works in Berlin. Working in video, photography and installation, his art has referenced the more tragic icons of his generation’s pop culture – Kurt Cobain, River Phoenix, Joy Division. For this piece, he has built the work from the physicality of the Polaroid itself, manipulating its end result and utilizing what would normally be a waste product from the development process. This diptych comprises the positive and negative image that is created when an old school, peel-apart Polaroid is taken. On the positive side, the background is obscured by a hand painted wall of silver marker, with the protagonist the only thing left visible in the shot. Only by closely studying the full, undoctored negative which sits adjacent in the frame can you discern the full picture and place the subject in their context.

Magda Delgado – Last Beauty before the End of Humankind I (2017)

Magda Delgado is an internationally exhibited artist, born in Lisbon, Portugal. The financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent recession that hit her home country caused her to emigrate, living in England, rural Germany and the mountains of Luxembourg. At the present time she is based between Nottinghamshire and Northumberland in the UK, and her birth city. A recurring reference point in her work has been Thoreau’s Walden: Or, Life in The Woods, and her imagery duly explores ideas of transcendence, abyss, mysticism and the natural world with humans removed. This image from 2017 is not only a beautiful example of Delgado’s work, but the film itself is a product of a laborious creative project: it’s the Polaroid 600 film produced by Impossible Project the instant photography enthusiasts who when Polaroid ceased film production in 2008 took over the last remaining factory in Enschede, Netherlands, and kept the format alive with their own editions of it.

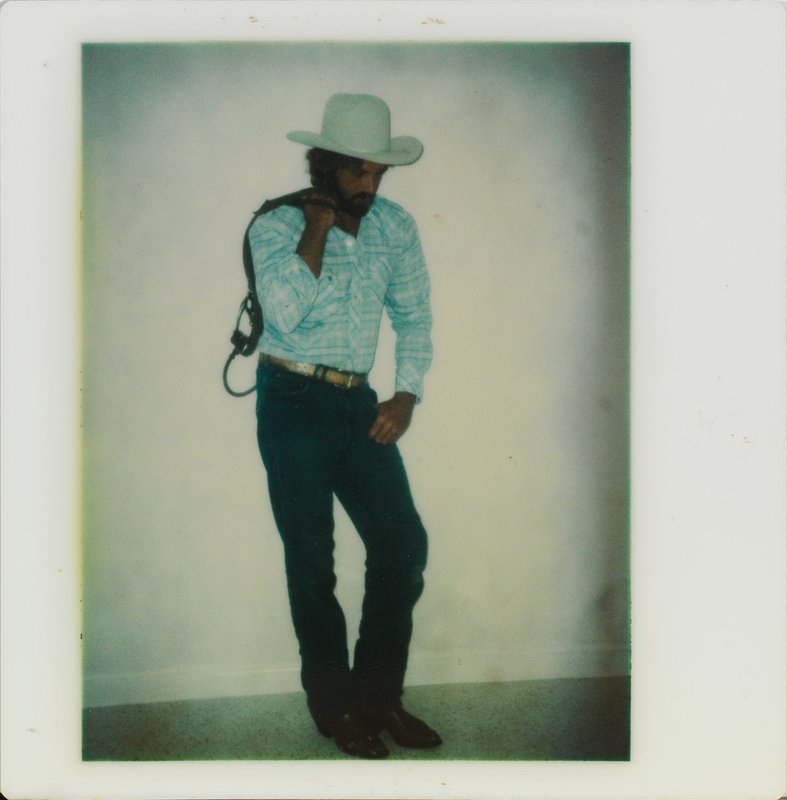

Duane Hanson created disarmingly realistic life-sized sculptures of ordinary people in mundane settings: a woman in a fold up chair listlessly overseeing a pile of junk at a flea market, children sitting on a rug to play a board game, a pensioner forlornly leaning on a chair for support. Detailed to the point of fine hair and faint bruises, these were archetypal portraits of the everyday people, tasks, and clothes which make up the bulk of life, both then and now. However, before they were sculpted from polyester resin, Hanson took Polaroid portraits of models staged in the same situations to work from. This image is a study for his 1984 sculpture, Cowboy. There are eight other similar studies available to buy here.

Related Articles

How to Perfect the Salon-Style Hang: An Easy Guide

Your First Step to Starting a Great Black and White Photography Collection

This is How to Perfectly Pair Your Artworks Using the Color Wheel