If you’re anything like us, summer is the time when you finally make a significant dent in the stack of books that accumulates throughout the rest of the year. Here are eleven books published in the last year that might have accumulated on your nightstand, and why now’s a great time to read them.

Known and Strange Things

Teju Cole

Teju Cole

Teju Cole

There’s no world in which I would surrender the intimidating beauty of Yoruba-language poetry for, say, Shakespeare’s sonnets, or one in which I’d prefer chamber orchestras playing baroque music to the horas of Mali. I’m happy to own all of it.

Known and Strange Things is Teju Cole’s first book since becoming a photography critic with The New York Times , and is also the PEN award-winning novelist’s first book of criticism. The collection of fifty-plus essays, which first appeared in various magazines, bring James Baldwin and John Berger into contact with Instagram and Boko Haram, to give an impression of a life and all its complexities understood through art, channeled by a mind acutely attuned to the role images play in shaping the world.

Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration

Ellen Mara De Wachter

Ellen Mara De Wachter

Ellen Mara De Wachter

Many artistic collaborations use some form of anonymity, from keeping their names secret to wearing masks. This impulse to remain anonymous sometimes involves creating an entity under whose name the artists make work: a way of transcending individual identity so that the creating entity becomes an artwork in its own right.

Curator Ellen Mara De Wachter’s credentials span the British Museum, Frieze , Artforum , and more, bringing her into contact with any number of prominent artists. In Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration , De Wachter interviews artist collectives—including Guerilla Girls , DIS, and Lizzie Fitch / Ryan Trecartin—for insight into collaborative practices, in an effort to break down the mythology of individual expressionism.

RELATED: How to Collaborate: 25 Leading Art Collectives Share Their Creative Processes, Part 1

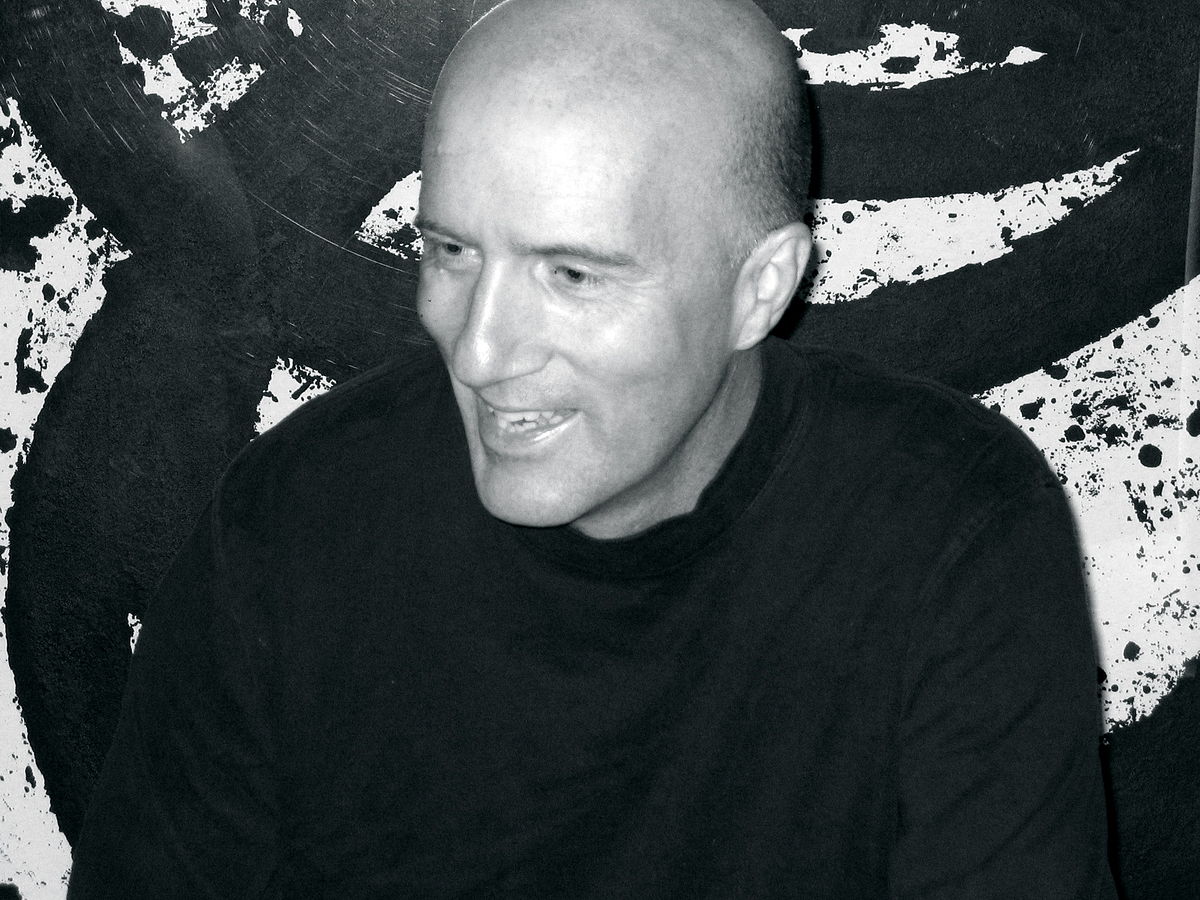

Typewriters, Bombs, and Jellyfish

Tom McCarthy

Tom McCarthy

Tom McCarthy

Here, as everywhere in Richter’s work, the gaze—of the artist, of the viewer—has been purged of sentimentality, of ideologies of “naturalness.” This is what sets him head and shoulders above his contemporaries Beuys and Anselm Kiefer—who, for all their brilliance, fall into the trap of uncritically reiterating the Romantic aesthetic that segued so seamlessly, with its fetishes of blood and earth, its sentimentalizing of history, into Nazism and finds its contemporary expression in vague cultural notions of authenticity and “spirituality.”

Tom McCarthy—whose novels Remainder (2007) and Satin Island (2015) deal with themes of repetition and authenticity that should be familiar to artists—published his first book of criticism this May. In fifteen essays, the novelist looks at the work of Gerhard Richter , On Kawara , and Ed Ruscha , among literary criticism and pop culture. McCarthy, despite his very recent recognition in the literary world, is no newcomer to the realm of visual art. In 1999, he cofounded, with Simon Critchley, the International Necronautical Society (INS). Inspired by the Surrealist writings of Georges Bataille, INS published a 1999 manifesto in The Times in which they write about their devotion “to mind-bending projects that would do for death what the Surrealists had done for sex.” INS has shown at Tate Britain; the Institute of Contemporary Art, London; the Drawing Center, New York; Kunstwerke, Berlin; and elsewhere.

Mounting Frustration

Susan Cahan

By the time the civil rights movement reached the American art museum, the movement had passed its peak. The first public demonstrations to integrate museums occurred in late 1968 and early 1969, twenty years after desegregation of the military and fourteen years after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, five years after the great March on Washington, four years after the Civil Rights Act, and three years after the Voting Rights Act. Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy had all been assassinated.

Art historian and Yale lecturer Susan Cahan wrote Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power to show how structural racism in New York art museums has yet to be eradicated. Though exhibitions like the Met’s “Harlem on My Mind” in 1969 (which didn’t include a single black artist from the neighborhood) and MoMA’s “Primitivism” in 1984 are often held as examples of the art world’s racial oversights, Cahan—an alumna of MoMA and the New Museum—argues that artists of color have still yet to achieve central status in museums equal to that enjoyed by white counterparts.

The Manhattan Project

László Krasznahorkai

László Krasznahorkai by Ornan Rotem

László Krasznahorkai by Ornan Rotem

I don’t feel like going to MOMA PS1 to see the exhibition entitled Greater New York, the one that everyone is flocking to, no, because I am afraid that I will only be confronted by yet another trendy display of tiresome, boring, fashionable watchamacallits, the way one art object copies another, and all of it strictly within a certain boundary that no one dares to cross, after all they are not exhibiting their objects here in order to cross certain boundaries, but to win their share of success, a success that is distributed exclusively within those boundaries. But my wife is annoyed, and says reproachfully that you can’t sit all day in your office at the Public Library, or at home—because that’s what you do, you just roost here in Manhattan and go nowhere, why, you could do this any where else, you did not need to come to New York just to cower in a hole, really—and she looks at me sweetly as she takes a new silk jumpsuit out of the closet, you’ve got to go out, socialize a bit, you’ve got to see what’s going on in the art world, for instance at MOMA PS1. No, I say, by God no. So, off we go to MOMA PS1.

László Krasznahorkai is perhaps best known for penning the novels that would become the basis for Béla Tarr’s films, earning him Susan Sontag’s oft-quoted descriptor, “the Hungarian master of the apocalypse.” Less known are his dizzying works of criticism published by Sylph Editions, which include a collaboration with German painter Max Neumann, Animalinside , and a single, torrential, 14-page sentence on Palma Vecchio, The Bill . Krasznahorkai’s latest book with Sylph, The Manhattan Project , is ostensibly a work of literary criticism. In a series of diaristic entries made while preparing a novel, the writer follows Herman Melville’s footsteps through Manhattan. Krasznahorkai’s journey mirrors that of Malcolm Lowry, who came to New York with a suitcase containing only a single rugby shoe and a tattered copy of Moby-Dick . Accompanying the letters are photographs of Krasznahorkai made by Ornan Rotem, who documented the writer’s journey, making for a compelling portrait of one of the most disturbingly creative minds alive today.

Eye of the Sixties

Judith Stein

Dick and Sheindi lived downtown on Cherry Street, a street on the way to nowhere. She remembered it from her childhood, when the fragrance of spices rode in on the breeze from the East River warehouses a few blocks away. Her Orthodox Jewish background was as foreign to Dick as the shape of his eyes and his shock of black hair were to her. She’d been charmed by his voice, a resonant baritone mellowed by smoke and alcohol. A onetime radio announcer, Dick read aloud all his beloved writers, especially Wallace Stevens. “The lover writes, the believer hears, / The poet mumbles and the painter sees, / Each one, his fated eccentricity / … living in change.” He might teasingly append “and the art dealer droolingly sells.”

Judith Stein is known for curating “The Figurative Fifties” and “I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1995. Her book Eye of the Sixties: Richard Bellamy and the Transformation of Modern Art is a biography of “art dealer and tastemaker” Dick Bellamy, who Stein argued was one of the last collectors who wasn’t in it for the money. Bellamy’s Green Gallery on 57th Street gave an early platform to young artists like Donald Judd , Claes Oldenberg, Dan Flavin , James Rosenquist , and Robert Morris . Stein’s story of the birth of the contemporary art market, written in vivid prose, is also a story of how a counterculture was coopted.

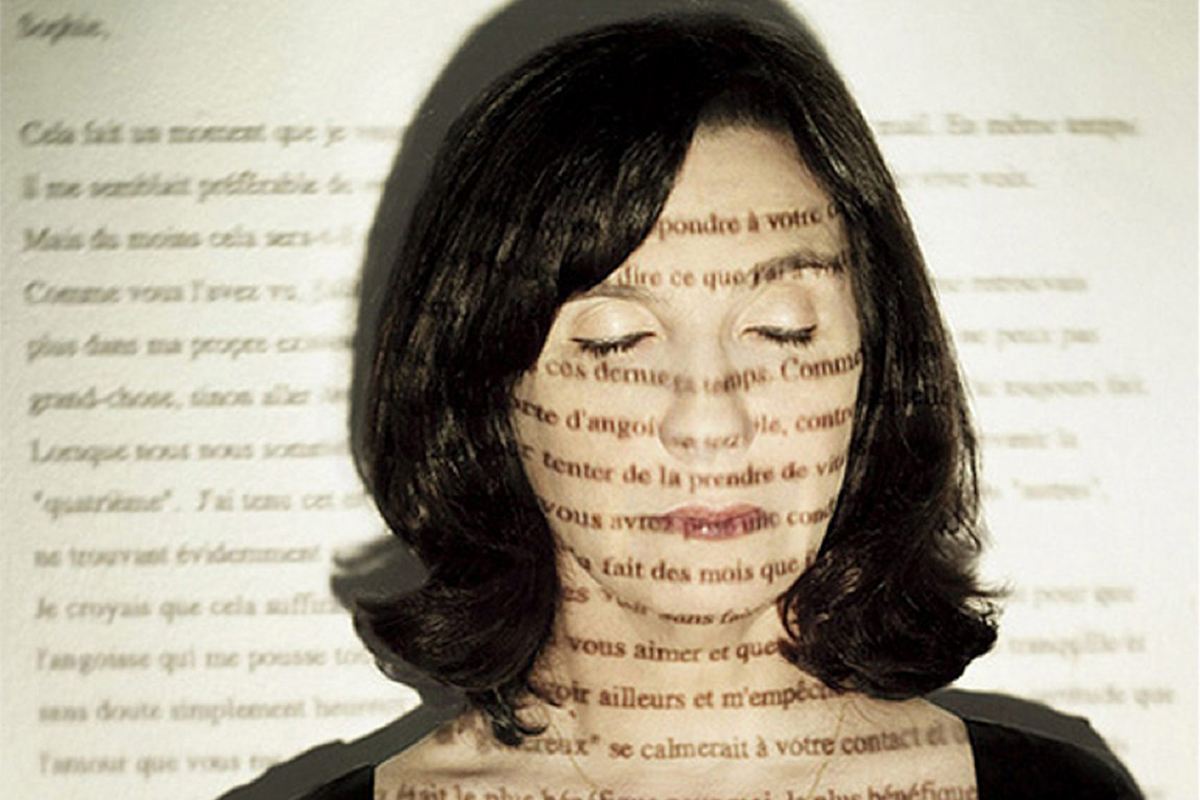

Rachel Monique

Sophie Calle

Sophie Calle

Sophie Calle

My mother liked people to talk about her. Her life did not appear in my work, and that annoyed her. When I set up my camera at the bottom of the bed in which she lay dying—fearing that she would pass away in my absence, whereas I wanted to be present and hear her last words—she exclaimed, “Finally.”

French artist Sophie Calle offers Rachel Monique as a sort of eulogy to her mother, Monique Szyndler, told through diary entries and family photographs. Chronicling the complicated relationship between the artist and her mother, an archivist for L’Express , Rachel Monique is a work that only really became possible after the matron’s death. Szyndler revealed her own history to her daughter only days before she died, leaving boxes of documents and photographers for her to sort through. Rachel Monique , which has also been presented as an installation, became a way for Calle to come to terms with their relationship.

Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency

Hal Foster

… To rethink transgression not as a rupture produced by a heroic avant-garde posited somehow outside the symbolic order but as a fracture traced by a strategic avant-garde inside this order. In this view, the goal of the avant-garde is not to break with the symbolic order absolutely (the dream of absolute transgression is dispelled) but to reveal it in crisis—to register its points not only of breakdown but also of breakthrough, that is, to register the points at which new possibilities are opened up by this very crisis.

With Hal Foster recently named the next Mellon lecturer at the National Gallery of Art, it’s worth revisiting his book on art and terrorism that was just released in paperback (it was published in hardcover in 2015). Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency focuses on works by artists like Thomas Hirschhorn , Tacita Dean , and Isa Genzken to ask how artists have predated or even predicted “a general condition of emergency instilled by neoliberalism and the war on terror.” Foster’s six lectures in Washington, DC next May will touch on similar topics. Channeling Giorgio Agamben’s assertion in Remnants of Auschwitz that artists and writers invent new language to treat unimaginable horrors, Foster will speak on the work of Jean Dubuffet, Asger Jorn, Eduardo Paolozzi , and Claes Oldenburg.

Honar: The Afkhami Collection of Modern and Contemporary Iranian Art

Mohammed Afkhami

Mohammed Afkhami

The deeper I became involved with Iranian art, the more I realized that I could play a role as a cultural emissary, opening people’s eyes to the rich heritage of this closed, misunderstood country.

More of a coffee table book than a beach-read, Honar: The Afkhami Collection of Modern and Contemporary Iranian Art is an invaluable look into a rich and textured history of art that’s unfortunately overlooked in Western museums. Following MoMA’s recent decision to hang works by artists from the six nations targeted by Donald Trump’s twice-failed ban, there’s been recent interest in the works by Muslim artists. Rather than allowing the works to disappear again back into the archives, Honar (Farsi for “art”) presents 250 contemporary and historical examples of Islamic art from Mohammed Afkhami’s prestigious private collection.

RELATED: No Easy Answers: Shirin Neshat Portrays the Women of the Iranian Revolution in Many Shades of Grey

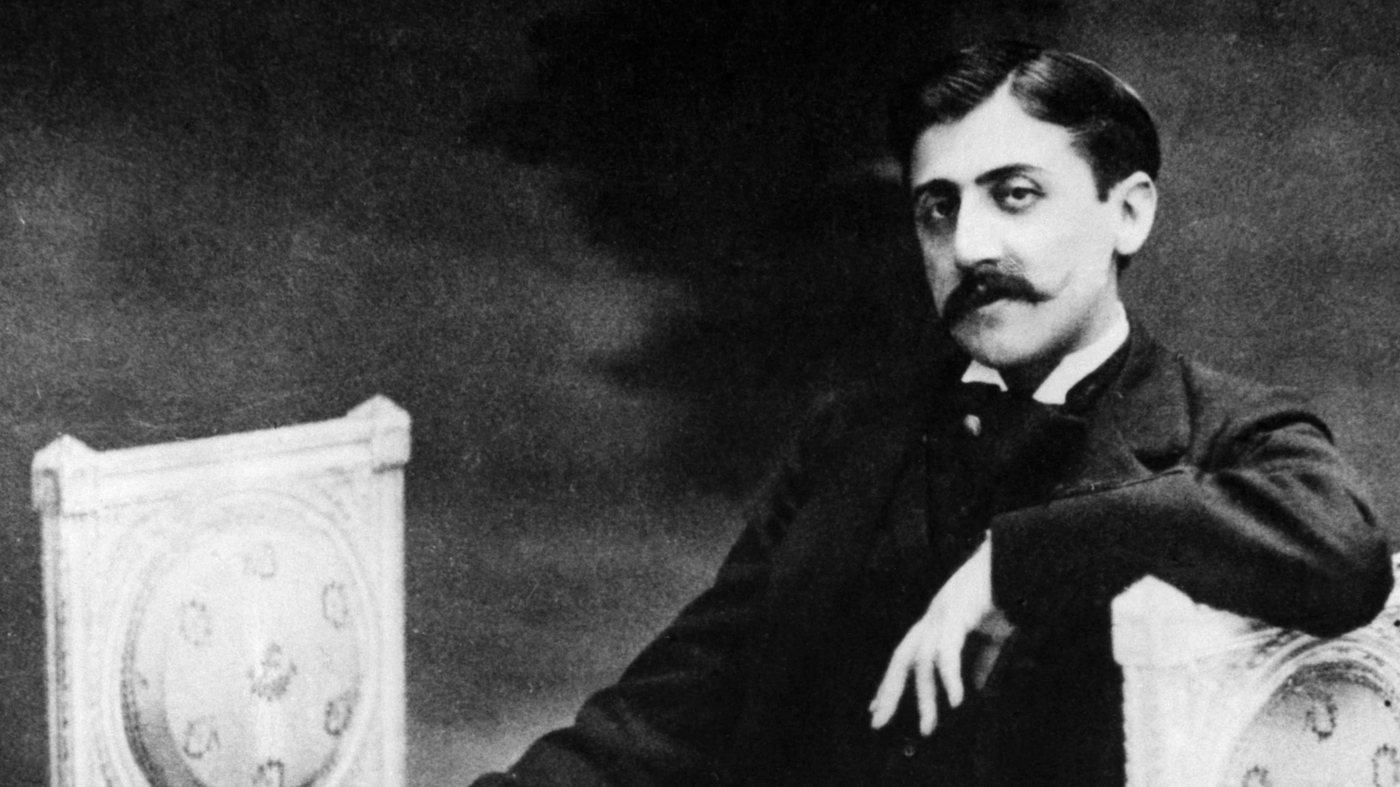

Chardin and Rembrandt

Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

You have seen objects and fruits that look as alive as people, and people’s faces, their skin, its fine down or unusual color, that have the look of fruit. Chardin goes further still, bringing together objects and people in these rooms that are more than an object, and even than a person perhaps, being the scene of their existence, the law of their affinities or contrasts, the restrained, wafted fragrance of their charm, their soul’s silent yet indiscreet confidant, the sanctuary of their past.

When criticism began, it was a thing for poets. Written when he was only 24 years old, Marcel Proust’s essay “Chardin and Rembrandt” was submitted to a newspaper in 1895, where it was rejected and summarily forgotten by all but fastidious scholars. Published by David Zwirner Books, Proust’s experimental essay is structured as a letter to a young man, much as Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet and Letters to a Young Painter , the latter of which Zwirner will publish later this year.

Reductionism in Art and Science

Eric Kandel

Eric Kandel

Eric Kandel

Bottom-up and top-down processing have not contributed to the beholder’s share in equal measure throughout the history of Western art. We can see this by comparing a Renaissance painting with an abstract painting. The Renaissance painting conforms to our brain’s rules regarding the normal extraction of information about depth from the pattern of light on the retina…. In abstract painting, elements are included not as visual reproductions of objects, but as references or clues to how we conceptualize objects.

Nobel Prize-winning researcher Eric Kandel writes with lucidity about neuroscience and abstract expressionism simultaneously (no small feat), arguing that reductionism was a useful method for both neuroscientists and post-war American artists in their parallel pursuits of understanding individual expression. At his strongest when discussing the neurological functions of the brain as it processes abstract imagery, Kandel brings in his research on top-down versus bottom-up information processing, and gives credence to artsy ideas like collective consciousness and the zeitgeist. However, Kandel’s narrative of art fails any test of historicity. Cursory treatment of the culture wars that raged in mid-century periodicals, for example, allows Kandel to cherry-pick quotes from both Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg as they suit his theory, with little thought given to the debates between the two critics, or why their disagreements still matter. Ultimately, Kandel’s preference for Greenberg’s formalist vocabulary (“gesture,” “tactility”) endangers reductionism to becoming little more than a scientific revival of formalism—which, admittedly, has never been more than a form of reductionism itself. Nevertheless, Reductionism In Art and Science remains an important book in that it shows scientists and artists have much to say to each other, and much to learn.

RELATED: What Did Harold Rosenberg Do? An Introduction to the Champion of “Action Painting”