When reading art history, it's easy to slip into imagining the artist alone in a dingy garret, awaiting the world to recognize his artistic glory. But the idea of individual genius is somewhat of a romantic conceit. In most cases, artists were also once students, perhaps plodding through school exercises, or emulating a mentor.

Take the exalted alumni of the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, Germany. In the last quarter of the 20th century, the university program in the Rhineland nurtured a remarkable number of young talents who would rise to be towering figures—particularly in the field of photography.

Marked by its distinctly dispassionate documentary style, this group became known as the Düsseldorf School of Photography, and their vaunted roster includes Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Petra Wunderlich, Laurenz Berges, Elger Esser, Simone Nieweg, Jörg Sasse, Axel Hütte, and Frank Breuer, among others.

To understand the development of one of the most remarkable artistic movements in Germany since Bauhaus, we took a closer look at the origins of the School, and how its conceptual approach ushered photography into the halls of modern art.

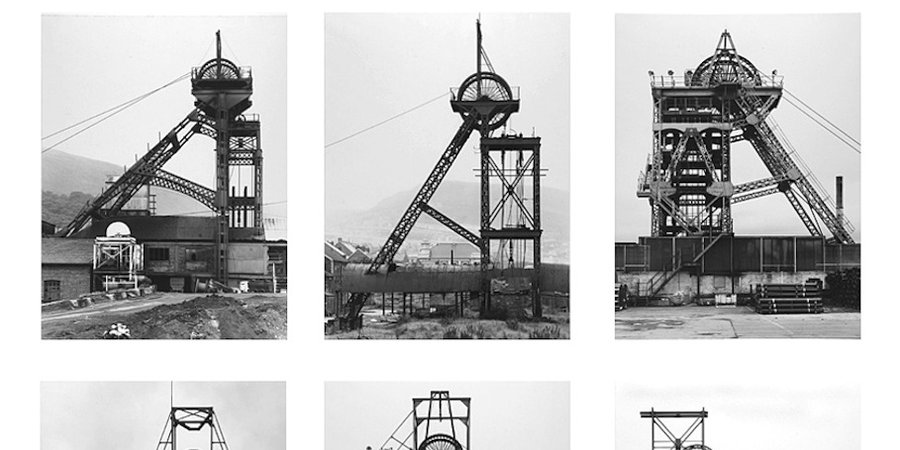

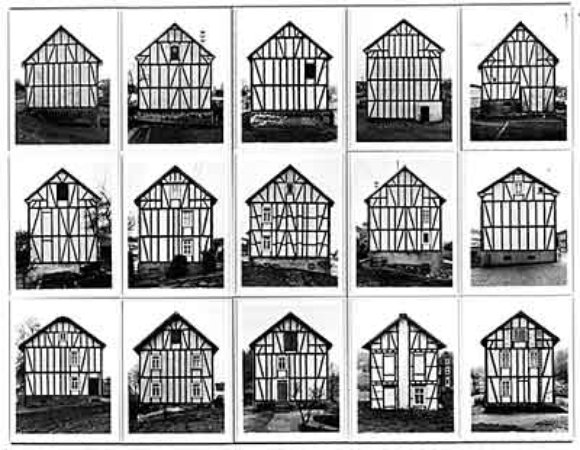

MEET THE BECHERS Bernd and Hilla Becher Framework Houses, 1959-73

Bernd and Hilla Becher Framework Houses, 1959-73

A number of auspicious circumstances conspired in favor of the photographers in Düsseldorf, from the latest printing technology accessible in the university’s laboratories to the many museums and galleries fringing the town. (Seminars with famed professors like Benjamin Buchloh and Kasper König didn’t hurt either; nor did the classes with Joseph Beuys and Gerhard Richter, both of whom were on faculty.) But most notably, from 1976 to 1996, there were two photography teachers: Bernd and Hilla Becher (who, because of policy matters, could never be simultaneously appointed at the Akademie).

Over their 50 years together, the husband-and-wife team shot some 20,000 photographs recording raw industrial structures across Western Europe: gas holders, blast furnaces, lime kilns, silos. When they began the project in 1959, Germany was still recovering economically from World War II, offering the Bechers a bleak laboratory of modern life, which they approached with taxonomical exactitude. They shot the looming—sometimes decrepit—factory complexes of the nation straight-on, cast against pallid skies as depthless and flat as white display panels.

In fact, there is something scientific, even clinical, about these studies: Like naturalists documenting species on the brink of extinction, the Bechers archived the remnants of industry being superseded by sleeker modern technology elsewhere. Following a stringent methodology, the Bechers grouped their work by subject into orderly grids, of pictures either 30 by 40 cm or 50 by 60 cm. As such, these image clusters invite viewers to find similarities and differences between the serial forms or “typologies”—water towers, for example, of varying diameters, cap shapes, and window sizes studding the base. “[W]e used the methods of natural history books,” Hilla Becher recalled to the Art Newspaper in 2011, “like comparing things, having the same species in different versions.”

But this was more than a conservation effort. A powerful conceptual force allied the Bechers with the projects of Minimal and Conceptual art. Well aware of it, the Bechers called their first monograph Anonymous Sculptures, in homage to Duchampian readymades. Like Duchamp, the Bechers inserted the colossal machines and structures from a desolate industrial landscape like found objects into a new context, that of art.

“The Düsseldorf School of Photography is linked to, and is the result of, the artistic emancipation of the medium,” writes the art historian Stefan Gronert. Going on, Gronert argues that their conceptual approach did nothing less than restore photography as the legitimate child of Western modern art. In 1970, the Museum of Modern Art in New York included the Bechers’ photos in a survey called “Information,” touted as the first conceptual art exhibition in the United States, and the images also landed a place in dOCUMENTA V in 1972 beside works by John Baldessari and Daniel Buren, among others.

BURNISHING A TARNISHED REPUTATION  Otto Steinert, Pedestrian’s Foot, 1950

Otto Steinert, Pedestrian’s Foot, 1950

The Düsseldorf School was a radical advancement in the history of photography—but particularly for photography in Germany. After being enlisted as a tool for Nazi propaganda, the medium was on trial as an illegitimate form of artistic expression by artists and intellectuals in Europe.

In the 1950s and 1960s, photographers worked assiduously to restore the medium’s tarnished reputation. Self-taught photographer Otto Steinert at the Folkwang-Schule in Essen was one such defender and tutored students like Timm Rautert and Ute Eskildsen, who had influential careers themselves, in the language of pictorial abstraction, or “subjective photography.” Think multiple exposures and blurred figures in motion, positive-negative reversal and bird’s-eye perspective. Think wild experimentation. Think… well, the Bechers thought the subjective photographers were overcompensating. “Steinert and the people of his generation did not want to look back,” Hilla Becher said in an interview in 1989. “[T]hey did not even want to look into the present, they just looked towards the future. It was a kind of escape.”

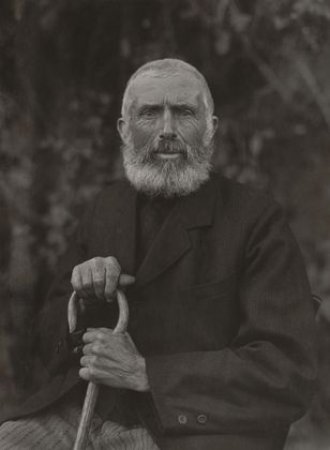

WHAT IS NEW OBJECTIVITY?  August Sander The Earthbound Farmer, 1910

August Sander The Earthbound Farmer, 1910

The Bechers, on the other hand, didn’t turn away from photography’s rich history. In fact, they harkened back to a prewar German photo movement called New Objectivity, whose members included Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patzsch, and most importantly, August Sander. Born in 1876 in Cologne, Sander set out to take 600 portraits of his countrymen, from priest to paper-hanger to peasant. His serious-eyed subjects are archetypes of society, collected by the camera lens; critic John Berger describes the plates as observationally rich as a page from an Émile Zola novel.

Nazis, however, deemed the subjects insufficiently Aryan, and with the rise of the Third Reich, Sander’s mission was cut short and he hid away his archive in the rural country. It wasn’t until the Bechers that his documentary methodology meaningfully resurfaced in art history.

FROM TECHNOLOGICAL TOOL TO ARTISTIC EXPRESSION  Thomas Struth Pergamon Museum IV, Berlin , 2001

Thomas Struth Pergamon Museum IV, Berlin , 2001

Despite their own directed path, as teachers the Bechers plowed wide and open artistic field for their students, and a vast variety of artistic approaches flourished at the Akademie. “It was important for [our students] to be made aware that they were doing something which was totally equal in merit to painting,” Bernd Becher has said. “I always explained to them that it must not be of practical use. That was the crucial criterion. They were not to create things, as they would at an arts and crafts college, that could be used to earn a living.”

In Hilla Becher’s words, “Everything connected with making pictures can be artistic.” Of their pupils, Candida Höfer shot waiting rooms, libraries, churches, and other public places as studies of psychologically fraught space. Like his masters, Thomas Struth shot one-point perspective of empty, unpopulated scenes, sometimes of the streets in Düsseldorf, and later in his career made pictures on a monumental scale: The photos in his museum series are as big as the paintings they depict.

Struth, along with Thomas Ruff, Jörg Sasse, and Axel Hütte incorporated portraiture into the documentary style of the School. Andreas Gursky pieces together a magisterial archive of modernity, like his mentors, aiming to create an “encyclopedia of life,” as he said in a 2001 interview. The photos by Frank Breuer, perhaps most alike in terms of subject matter to that of his mentors, captures the exteriors of corporate warehouses such as Nike.

And the story of the School isn't over. The Becher students continue making photographs, and in 2008, Bernd Becher’s named department position was taken over by Christopher Williams, whose retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened this week, continuing to open up the conceptual possibilities of the medium.