When writer Pauline Kael called David Lynch "the first popular Surrealist," it wasn't a dig against Andre Bretton and his cohort of avant- grade artists in 1930s Europe who were influenced by the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud. Lynch's popularity, cultivated largely outside of the art world's ivory walls, and his brand of surrealism are both of an entirely different ilk.

The filmmaker has earned international renown for his unsettling, gloom-Pop films since Eraserhead, his cinematic debut, was released in 1977. The success of that movie led to Lynch's being asked to direct Dune in 1984, which should have launched the director into mainstream success. Instead, the film flopped; but its failure meant that Lynch turned back to a more personalized, highly stylized oeuvre. It was his following efforts—especially the CBS television series Twin Peaks(1990–91) and the movies Blue Velvet(1986) and Mulholland Drive (2001)—that would come to exemplify Lynch's Surrealist tendencies as noted by Kael.

What many fans of Lynch's cinematic oeuvre don't realize is that he started out as a painter, studying the medium in art school at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. And though the young artist quickly began to experiment with moving images, he never stopped drawing and painting, either; in 2007 his work in visual art was the subject of a major retrospective, "The Air is on Fire," at Paris's Fondation Cartier, which included paintings, drawings, sound works, and installations made specially for the show. Cultivating a unique style that is as complex, dark, psychologically-attuned, and oddly funny as his filmic work, Lynch has quietly produced a whole body of graphic work in drawing, painting, and printmaking that extends and widens his surrealistic sensibility. Here are a few ways of looking at his art.

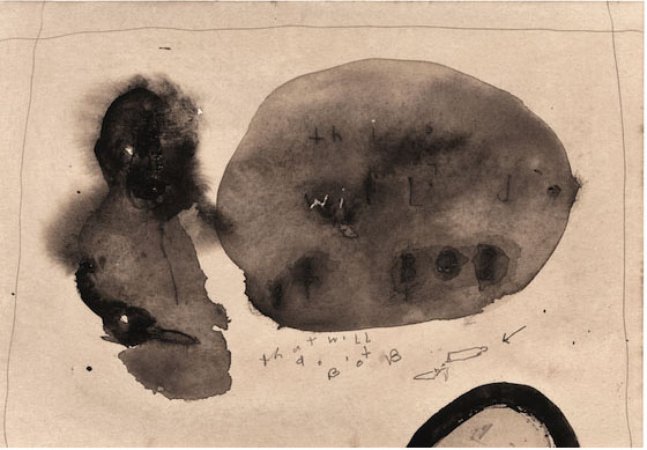

That Will Do It Bob (2008-9)

That Will Do It Bob (2008-9)

Lynch frequenly uses fragmented pieces of text that correlate, to a certain extent, with his images, and point to narrative interpretations that leave much to the imagination. He uses text impressionistically, rather than as descriptors or captions to the images, evoking "naming" as the Biblical act of spiritual bestowal, and inviting exegetic interpretation. In works like That Will Do It Bob (2008-9), pictured above (and perhaps referencing the horrifying occult villain of "Twin Peaks"), the text itself is treated as a graphic element, used for its aesthetic effect as much as for its meaning, and partially obscured by the pooling of overlaid ink. Lynch has compared the use of letters as structural elements in his paintings to "teeth"—in other words, they're ambiguously decorative and functional, and also bestow on the painting an uncanny grin.

Untitled (1 Dark) (1999) is available on Artspace for $3,000

Untitled (1 Dark) (1999) is available on Artspace for $3,000

It would be a mistake to interperet Lynch solely as a purveyor of doom and gloom—on the contrary, for Lynch, darkness isn't death, it's the carrier of infinity, the darkness of the cosmos. As Lynch has said, in darkness, "there's always something else, something unseen. The world is infinite rather than finite."

Since 1973, Lynch has been a vocal proponent of transcendental meditation, a practice that is said to reduce stress hormones, improve memory, alleviate anxiety and depression, and yield a host of other healthful benefits. (In 2005 he launched the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and Peace to promote the teaching of the practice.) The aesthetic influence of this practice is evident in Lynch's embrace of a kind of mute expressionism found in darkness, using little color in his minimal compositions. Even in works like Flying Woman (2010, below), the composition is oddly static; all is at a standstill.

Flying Woman (2010)

Flying Woman (2010)

As in his films, Lynch's work in the visual arts are permeated by a sense of foreboding that is sustained, rather than resolved. Films like Mulholland Drive take up popular genres but make a point of breaking from expected narrative paths, veering off into, and then back out of, the unknown. It's a kind of narrative style that's been referred to as "dream logic," describing events that somehow make sense despite their evasive unfoldings. In the similarly dreamlike scenes they depict, Lynch's visual works are like screenshots from yet-to-be-realized films, their curiosity stemming from their breakage from typical narrative structures and impressionistic layers of meaning. Symbolism plays a major part in this effect, making the reference to Surrealism particularly apt when discussing Lynch's work in painting.