Some people might tell you that taking in a work of art is no different from gazing upon a beautiful flower, or a spectacular sunset. But ask yourself: do you really know how to look at a flower? Can you parse the various biological marvels on display? Are you perhaps missing something? Art is no different—there are places to inspect, aspects to weigh, artistic skills to suss out and savor. These, of course, will differ from person to person, but here are a few things to look for (other than the obvious beauty-related ones) that will help you really, truly appreciate a work of art.

1. HOW WAS IT MADE?

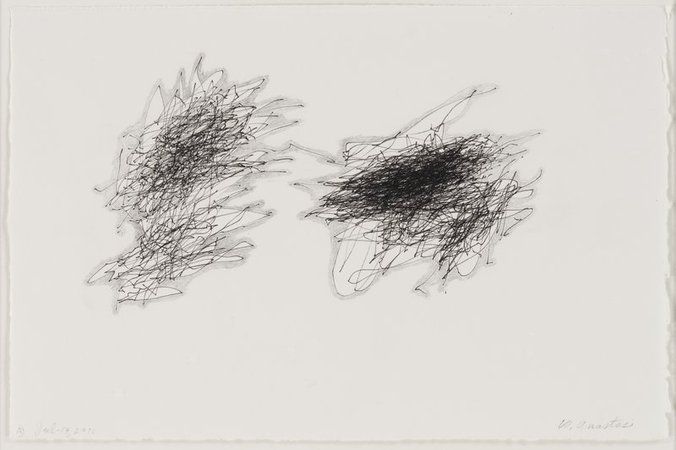

William Anastasi’s Untitled (Method & Madness A) Jul. 19, 2010, 2010 – $16,000 on Artspace

William Anastasi’s Untitled (Method & Madness A) Jul. 19, 2010, 2010 – $16,000 on Artspace

When you look at it, most art just sits there, static, a picture or object on display. But the sensitive eye can rewind the video tape, so to speak, and read the way the artwork was constructed. Were the brushes laid down fast or sedulously? Where was the camera placed? Like a detective at a crime scene, take the time to unravel the way the artwork in front of you as a record of a performance—one that expressed the artist’s virtuosity.

2. WHAT'S IT MADE OUT OF? (BE CAREFUL)

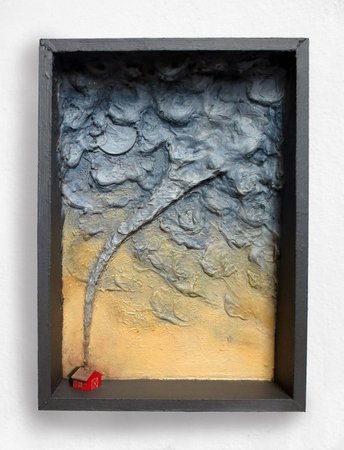

Laura Murray’s Oklahoma Study #7, 2015 – $700 on Artspace

Laura Murray’s Oklahoma Study #7, 2015 – $700 on Artspace

Artists, modern-day alchemists, love to transmute. A nail poking out from a stick of wood, in the hands of Susan Collis, can be pure platinum; a church by Al Farrow may be made from bullets; Amber Cobb’s cloth dangling from the wall might be silicone. As for paintings, marvel in the fact that each stroke of paint consists of pigment—essentially, colored dirt—suspended in viscous matter, which the artist conjures to do their bidding.

3. DOES IT SET YOU FREE?

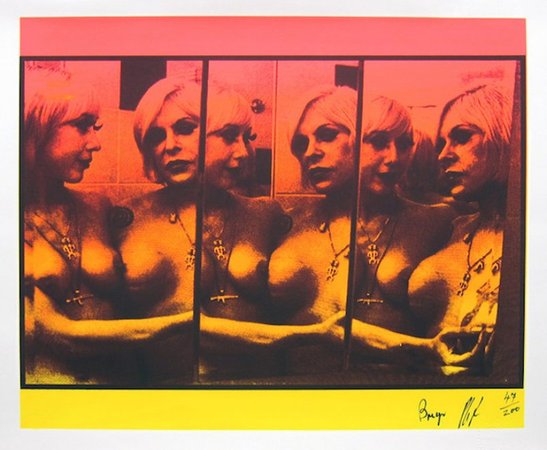

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’s Triple Androgyne, 2014 – $150 on Artspace

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’s Triple Androgyne, 2014 – $150 on Artspace

Artists often operate from a step off the mainstream, using an outsider’s vantage to offer new perspectives on things we often take for granted and suggest possible alternatives. These can relate to anything from the way Picasso saw a bull’s head in a bicycle seat to Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographic revelation that male sexuality has a wide ranges of orders that aren’t listed on the normative menu. Allow these works to untether your imagination.

4. HOW DOES IT CONNECT TO OLDER ART?

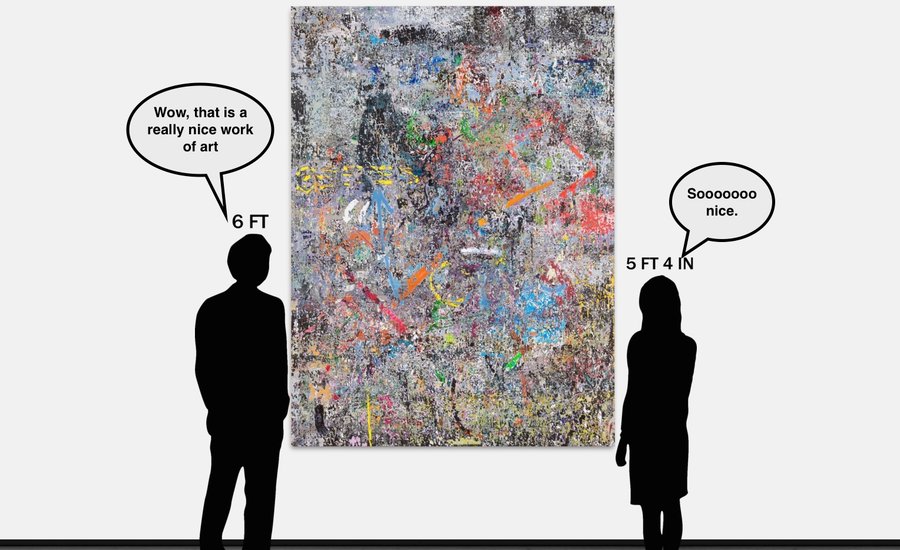

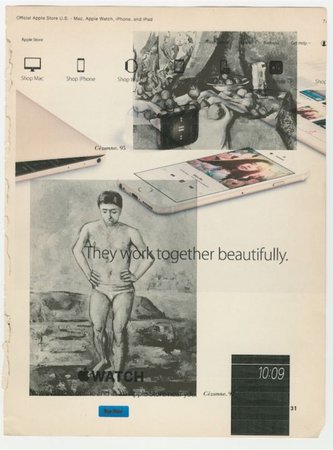

Wade Guyton’s Untitled (They Work Together Beautifully), 2015 – $10,000 on Artspace

Wade Guyton’s Untitled (They Work Together Beautifully), 2015 – $10,000 on Artspace

Harold Bloom wrote of the “anxiety of influence,” and artists are acutely aware of their places within the traditions of their mediums. Sometimes, as in the case of Jose Dàvila, they try to harmonize with their artistic forebears, making work with reverent reference to what came before; others, like Alan Magee, strive to exorcise their influences. As with a note on a musical score, the artwork you’re looking at may depend on one that came before for its meaning. Try to determine if that’s the case.

5. HOW DOES IT CONNECT TO SOCIETY?

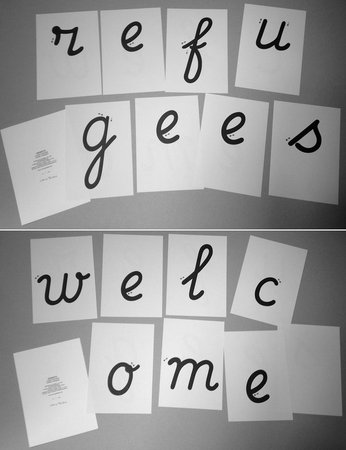

Claire Fontaine’s Untitled (refugees), 2015 – $130 on Artspace

Claire Fontaine’s Untitled (refugees), 2015 – $130 on Artspace

Art doesn’t have to be “about” anything, really, but sometimes it’s about you. Or your friends. Or your political order. Or the fate of people half a world away. Artists frequently use their position to put their own particular lens on society, illuminating ills, underscoring hypocrisies, offering potential futures, or delving into resonant traumas of the past. If that’s the case, take the time to decode and absorb the artist’s message.

6. IS IT AVANT-GARDE?

Brenna Murphy’s opal resonancy valley, 2014 – $4,000 on Artspace

Brenna Murphy’s opal resonancy valley, 2014 – $4,000 on Artspace

Think of artists as the scouts of their tribe, slipping out in the early half-light to explore the uncertain terrain ahead. What they bring back might not look like art—it might be confusing, unrecognizable, irritating. When you see a work that you just can’t place—as in, it’s not a painting or anything else you’ve seen before—and its disagreeability makes you uneasy, pay close attention. It may be the next breakthrough in art.