The following was excerpted from Phaidon's "Art and Ideas" series book, Art Nouveo:

Extraordinary things were afoot in the visual arts at the turn of the nineteenth century. Between about 1890 and 1910 artists, designers and architects from Paris to St Petersburg, from Brussels to Buenos Aires, produced work that evoked the spirit of the age at the same time as provoking the bitterest critics. Since its brief apogee, this work, which contemporaries labelled Art Nouveau, has continued to fascinate, disturb and inspire us in equal measure.

The mention of Art Nouveau, also then known as the ‘modern style,” over a century after its triumphal appearance at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900 conjures up images of feminine curves, organic tendrils, and linear forms. In the popular imagination Art Nouveau brings to mind seductive posters for French musical reviews or the sinuous ironwork of the Paris Metro stations. Museums proudly display their examples of opaque naturalistic glassware and contorted carved furniture, representatives of a now alien style that brought the old century to a close and heralded the new.

Yet, the influence of Art Nouveau reached far beyond the streets of Paris, and its aesthetic was far richer than mere organic fantasy. For alongside the tumbling arabesques caricatured in a contemporary cartoon, Art Nouveau also encompassed the geometry and radical simplicity of Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow and the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop). Early centers of the style included Brussels in Belgium, Nancy in France and Munich in Germany, as well as Paris. Moreover, the style also accommodated designers across central and eastern Europe, inspired in part by their own specific national traditions.

The pan-European nature of Art Nouveau resulted in a correspondingly diverse nomenclature. In Germany it was Jugendstil, in Austria and Hungary it was the Secession style, and in Barcelona it was part of the broader Modernista movement. In Italy it was La Stile Liberty, named after the London shop Liberty’s, which was perceived, by the Italians at least, as the fount of the new aesthetic. In England and America practitioners whom we might now describe as Art Nouveau were still considered to be part of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Art Nouveau not only spread across Europe; it manifested itself wherever Europeans went. It became a global style, one that, in different hands, could be both imperial and nationalist.

As well as being aesthetically varied and genuinely international, Art Nouveau was also an incredibly versatile style. Noting within architecture and the decorative arts escaped its influence, from door handles to chairs, chandeliers to apartment blocks, wallpapers to shop fronts. The style had no respect for the boundaries of class or quality. The finest luxury objects were conceived and handcrafted in the Art Nouveau manner, as was the cheapest jewelry and the most ordinary industrially produced tableware, along with all manner of printed ephemera. This dichotomy meant that Art Nouveau embodied all the tensions within art, design, and society at the turn of the century. In its variety of manifestations Art Nouveau was both elitist and populist, private and public, conservative and radical, opulent and simple, traditional and modern.

Copious amounts of ink were split by critics at the 1990 Universal Exposition over the merits and failings of Art Nouveau, proof that it was a highly self-conscious style. This peculiar self-consciousness was a product of the role Art Nouveau played in the history of late nineteenth-century design. Heralded as revolutionary by some of its mentors (and damned for the same reason by some of its detractors), it came at the end of a century that for the most part had seen architecture and the decorative arts gradually descend into a rut of increasingly derivative historicism. Past styles were endlessly regurgitated in debased fashions until they resembled pastiche. The great exhibitions of the nineteenth century were characterized by incongruous combinations of Renaissance, Baroque and classical styles that revealed an unease with the progress afforded by the industrial age. Radical Art Nouveau designers set out to shatter historicism and create a style appropriate to their time, the age of cinema, the telephone, and the automobile. Yet the more conservative embarked upon a mission to rescue the guiding principles of traditional craftsmanship and elegance, to update them rather than overthrow them.

In either case, Art Nouveau was perceived as being much-needed, and in some ways long-awaited. When it arrived, the style was the product of an extended gestation period and had a brilliant, albeit, brief, lifespan. The movement took shape in the 1880s and 1890s, burst onto a wider public at the 1900 Universal Exposition, but was largely eclipsed after 1914. If Art Nouveau saw itself as a reaction against an aesthetically corrupt century, it was also a product of it. In order to explain Art Nouveau it is necessary to survey a maze of interlinked influences, from the Gothic and Rococo revivals, to the Arts and Crafts Movement and the Aesthetic Movement, as well as the political and economic motives of those who engendered its development.

All these apparently contradictory facets mean that the study of Art Nouveau offers a fascinating insight into the often schizophrenic mind-set of an age. Through the style we can see the fears, anxieties, hopes and dreams of the fin de siècle , but Art Nouveau has also lived on as an influence and a propaganda tool for both its friends and enemies. First came the immediate period of disdain. The Modern Movement pilloried the organic ornament of Art Nouveau as the last gasp of bourgeois decorative excess, while claiming the more geometric Viennese tradition as the parent of its own functionalism. What was once so fashionable inevitably fell out of favor—the French even threatened to knock down the Art Nouveau entrances to the Paris Métro in the 1930s. Yet at the same time Art Nouveau effectively evolved into Art Deco, the modern decorative style of the inter-war period (which was equally reviled by the more zealous Modernists).

After World War II, Art Nouveau gradually evolved as a subject fit for scholarly study. Then came the revivals. Although Scandinavian and Italian post-war design never forgot the organic roots it shared with Art Nouveau, it was not until the 1960s that the psychedelic movement on the West Coast of America and Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba store in London brought the style back into vogue. As this initial burst of pop-revivalism evolved into an intellectual critique of Modernism, Art Nouveau, together with Art Deco, provided the new alternative decorative history of twentieth-century design.

Below are nine of the most significant practitioners of the period.

AUBREY VINCENT BEARDSLEY

1872-98

English graphic artist

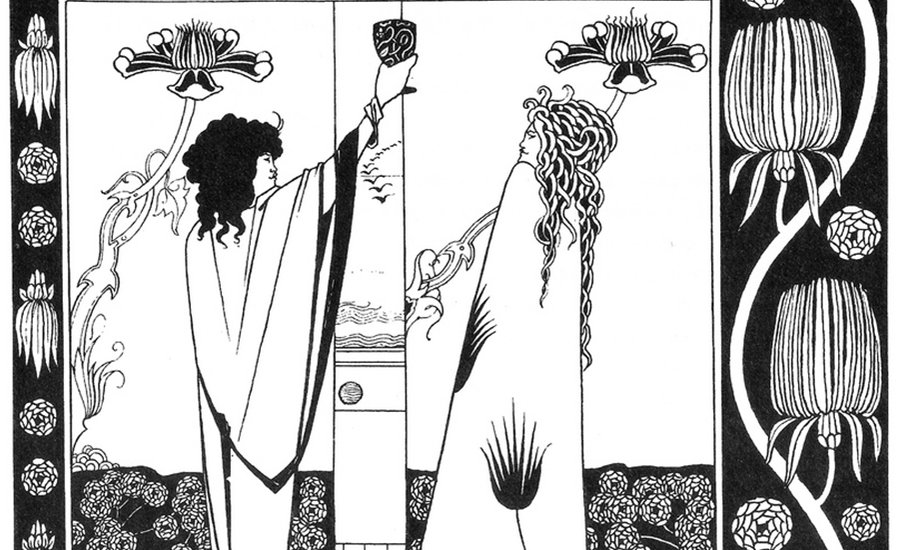

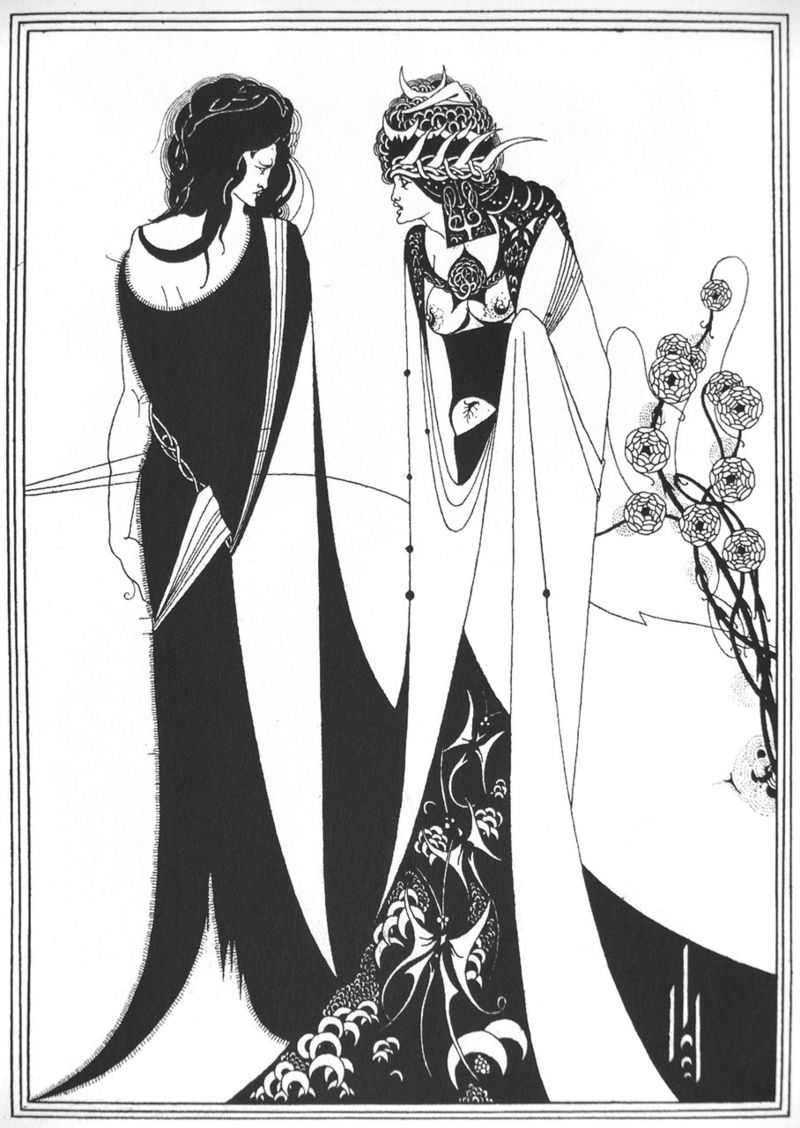

Illustration for Salome

Illustration for Salome

Beardsley’s linear style, rendered in pen and ink, was among the earliest manifestations of mature Art Nouveau. He came to widespread attention through his illustrations for Sir Thomas Malory’s Le More d’Arthur in 1893 and 1894. His 1894 illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé remain his most famous work; in the same year he became art editor of The Yellow Book , the flagship of the Aesthetic Movement in London. By 1896 Beardsley had adopted a more intricate manner to depict the finery and decadence of 18th-century France. In 1897 the tuberculosis he had suffered from since childhood worsened, leading to his death at the age of 25.

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC

1864-1901

French painter and graphic artist

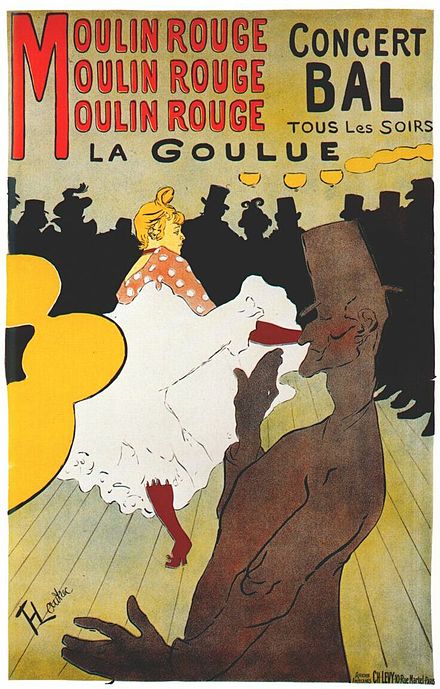

Moulin Rouge: La Goule

(1891), poster

Moulin Rouge: La Goule

(1891), poster

Toulouse-Lautrec began painting in Paris in the 1880s and studied under the Symbolist Émile Bernard, exhibiting at the Salon des Indépendants from 1889. In 1891 he designed his first posters, for which he received widespread acclaim. His posters brought his stylized representations of decadent Parisian life to a broad public.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

1867-1959

American architect and designer

Between 1888 and 1893 he worked in Chicago for Louis Sullivan, and the influence of Sullivan’s organic forms is apparent in his designs and writings. Wright’s early work displays close parallels with the development of Art Nouveau in Europe. From 1901 to 1913 he built a series of “prairie houses” that combine low geometric forms and spaces with stylized ornament. For Wright, natural setting was crucial to his designs.

GUSTAV KLIMT

1862-1918

Austrian painter and designer

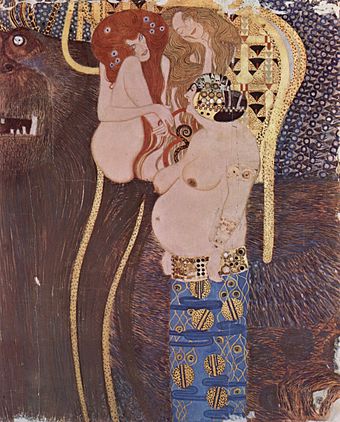

A section of the

Beethoven Frieze

, 1902

A section of the

Beethoven Frieze

, 1902

Klimt opened a studio in 1883 after training at the School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna. His early paintings were academic in style, but he became increasingly influenced by Symbolism, provoking bitter criticisms from Vienna’s artistic establishment. Klimt was one of the founders of the Secession in 1897, becoming the group’s first president; he also set up the journal Ver Sacrum. The Beethoven Frieze , painted in 1902 to decorate the Secession Building, signaled an even more stylized aesthetic. Klimt remained a prominent figure in the Secession until he resigned in 1905. He was associated with the Wiener Werkstätte, his most notable contribution being his friezes for the Palais Stoclet in Brussels designed by Josef Hoffmann in 1905-11.

PAUL GAUGUIN

1848-1903

French artist

Still Life with Japanese Woodcut

(1889)

Still Life with Japanese Woodcut

(1889)

Gauguin was born in France and brought up mainly in Peru. He became a banker in Paris, but painted in his spare time and exhibited with the Impressionists from 1878. In 1883 he gave up his job and his relations with his family broke down. Gauguin worked with Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne in Pontoise. He became the leader of the Pont-Aven group in Brittany between 1886 and 1889, and developed a distinctive brand of Symbolism, using simplified decorative lines and flat bright colors inspired by Japanese art to represent mystic and primitive subjects. From 1891 he lived for extended periods in Tahiti.

WILLIAM H. BRADLEY

1868-1962

American graphic artist

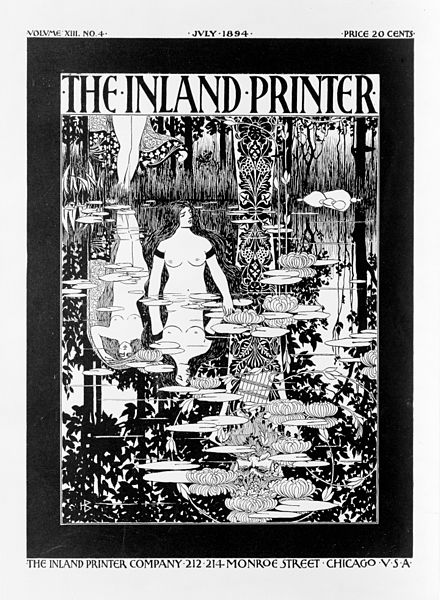

Cover of the

Inland Printer

, 1894

Cover of the

Inland Printer

, 1894

Bradley’s work drew on the contrasting influences of William Morris and Aubrey Beardsley and his illustrations were among the earliest examples of American Art Nouveau. Trained as a wood engraver in the mid-1880s, he turned to line engraving as his first technique became obsolete. His covers for the Chicago journal Inland Printer in 1894 established him as an exponent of the new style, and he gained widespread acclaim for his posters for another Chicago publication, The Chap Book . In 1895 he returned to his birthplace Massachusetts, where he turned to traditional printing methods, the result being his own periodical Bradley: His Book . He exhibited work at the Paris gallery of Siegried Bing in 1895, but by 1900 his career was in decline and thereafter he worked largely in commercial printing and type design.

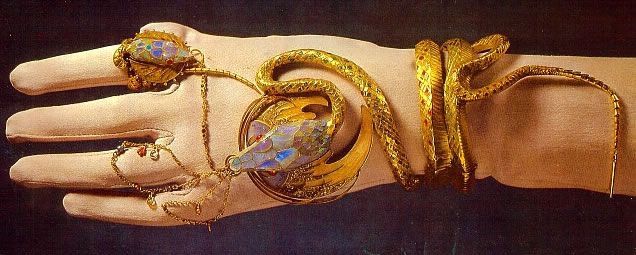

GEORGES FOUQUET

1862-1957

French jeweler

Bracelet Madea (1899) made for actress Sarah Bernhardt, made in collaboration with Alphonse Mucha

The son of a goldsmith, Fouquet took over the family firm in 1895 and soon adopted the Art Nouveau style. In 1900 he produced jewelry designed by Alphonse Mucha and won a gold medal at the Paris Universal Exposition. Much also created the interiors of Fouquet’s shop in 1901. Although initially inspired by nature and Japanese art, he went on to make more geometric pieces with Egyptian motifs, resulting in a revival in his fortunes in the 1920s with the advent of Art Deco.

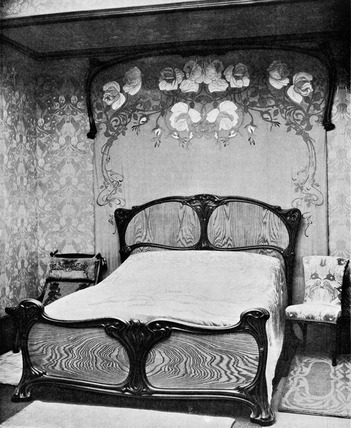

EUGÈNE GAILLARD

1862-1933

French designer and architect

Chambre Ó coucher at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition

Chambre Ó coucher at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition

Gaillard rejected a career in law to take up interior design and decoration. Siegried Bing employed him alongside Georges de Feure and Edouard Colanna to create interiors for his pavilion at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition. The abstract natural forms of his furniture reflected a mistrust of historicism and he became a vocal advocate of modern design. Around 1903 he left Bing’s atelier and set up his own firm. In 1906 he published A Propos du Mobilier (On Furniture.)

MARGARET MACDONALD

(1865-1933)

&

CHARLES RENNIE MACKINTOSH

(1868-1928)

House for an Art Lover (1901)

House for an Art Lover (1901)

Macdonald was a painter and designer who worked closely with her husband Charles Mackintosh, a Scottish architect, designer, and painter, whom she met at the Glasgow School of Art. Mackintosh was taken on by the architects Honeyman and Keppie in 1888, where he met the artist Herbert MacNair. Mackintosh developed an individual style with Symbolist overtones. In 1894, he exhibited with MacNair, Macdonald, and her sister Frances for the first time. Mackintosh is best remembered today for his post-1895 work, beginning with the Glasgow School of Art (begun in 1896) and followed by tea rooms for Catherine Cranston. Mackintosh and MacDonald also received decorative commissions, the most celebrated being the Hill House (1902-4) in Helensburgh. His success declined in the years after 1905.