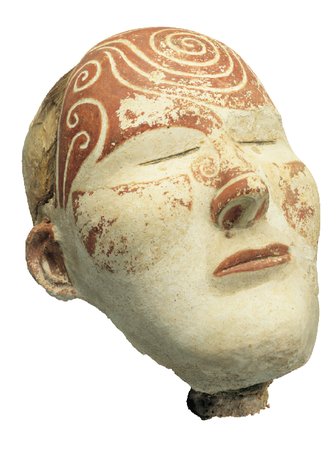

It’s Halloween, which in the United States means that the young (and young-at-heart) are busily crafting their costumes for a night of tricks and treats. For many cultures around the world, however, the wearing of masks and similar disguises is hardly “something for the kids.” Masks figure into some of humanity’s most enduring rituals, going at least as far back as the ancient Egyptians. To learn more about this rich history, we’ve excerpted this list of 10 masks from Phaidon’s30,000 Years of Art.

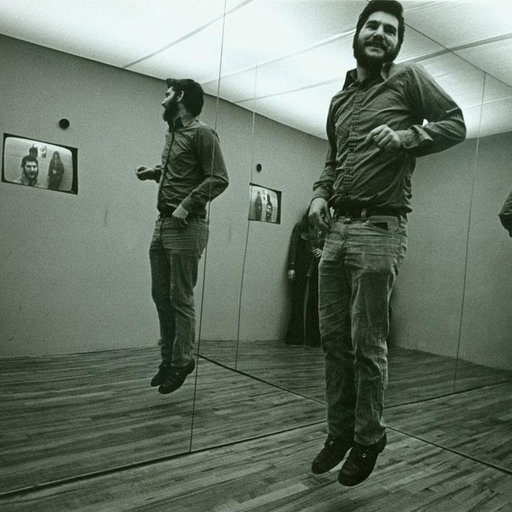

MASK OF TUTANKHAMUN

New Kingdom, Eighteenth Dynasty, Egypt

c. 1327 BC

The mask of King Tutankhamun (c.1336–1327 BC) is one of the most readily recognized icons in Egyptian art. It was found on the king’s mummy buried in the Valley of the Kings, on the west bank of the Nile opposite modern Luxor. The tomb was discovered by the English archaeologist Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon in November 1922.

The youthful king is shown wearing a nemes, a striped royal headcloth, with the heads of a vulture and a cobra – the symbols of the protective goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet. He has a ceremonial beard attached to his chin and a broad collar with hawk-head terminals around his neck. Heavy cosmetic lines accentuate the king’s eyes. The mask is made of gold with inlaid semi-precious stones, glass, and faience. An inscription from the so-called Book of the Dead is incised on the back.

The face is the most important identifying feature of a person, and in order to preserve it the ancient Egyptians affixed a mask over the mummy’s shoulders and head. This does not mean that we should regard Tutankhamen’s mask as his portrait; it was, rather, an idealizing image that conformed to the established Egyptian notions of how this king was represented.

HELMET AND VISOR

Aramaean Culture, Syria

c. AD 50

The kingdom of Emesa (modern Homs) in Syria grew wealthy as a result of its key position on trade routes between the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East. This helmet was found in the royal necropolis there and was clearly intended for use by a member of the high elite, probably the king himself.

Despite the artistry of the silver mask, it seems that the helmet was designed for combat as well as was designed to be used in ceremonial purposes, for the pierced teardrop holes under the eyes serve the practical function of increasing the wearer’s field of vision. Some textual support for this interpretation comes from the Greek historian Arrian (b. c. AD 86) who described masked participants in tournaments held among the Roman cavalry. Those areas of the iron helmet not coated with silver were originally covered with textiles, now lost. The focus of the piece, however, would always have been the beautiful silver mask, which may even have been modeled after the features of its owner.

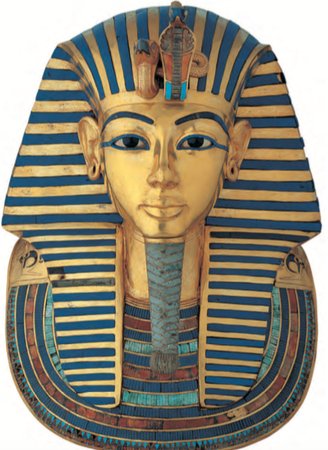

TEOTIHUCAN VOTIVE MASK

Teotihuacan Culture, Mexico

c. AD 300

This mask is one of many artworks made by an earlier culture that the fifteenth-century Mexica (one of several peoples commonly referred to as Aztecs) deposited as offerings in sacred buildings of the ceremonial precinct at Tenochtitlan, the Mexica capital. Dated to the early Classic Period (c. AD 200–400), the mask was made by a Teotihuacan artist who lived 1000 years before the Mexica. Typical of Teotihuacan ceremonial masks are the use of a dense and dark metamorphic stone, a highly smoothed surface, the triangular form of the face and the flange-like ears. Their function remains unknown, although their weight and flat inside surface make it very unlikely that living people wore them.

The mask was discovered underneath the main entrance stairway of the temple dedicated to the Mexica patron deity known as Huitzilopochtli. As a contemporary offering with origins in the distant past, it served to link the Mexica, a lowly nomadic people from Mexico’s northern deserts, to the illustrious Teotihuacan culture of the past. At its apogee, around AD 400, Teotihuacan was the most powerful social, political and economic force in Mesoamerica and boasted the world’s second-largest city, surpassed only by imperial Beijing in China. Teotihuacan’s fame did not dissipate with its fifth-century demise, but instead enjoyed legendary status among subsequent Mesoamerican cultures for hundreds of years.

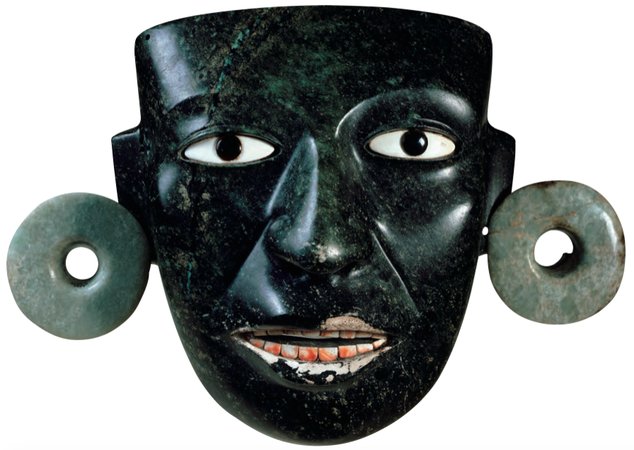

DEATH MASK

Tashtyk Culture, Russia

c. AD 300

This rare and distinctive female death mask, dated to the third or fourth century AD, comes from Oglakhty burial VI, grave no. 4, in the Khakassia Republic of southern Siberia, near Mount Oglakhty, on the banks of the River Yenisey.

The complexity of detail needed to identify its find location is indicative of the nomadic nature of the steppe people who created it. The function of the mask was to prevent the return of the deceased to the world of the living as an evil spirit, as well as to capture permanently the living image of the dead person. The incised ochre paint suggests tattoo markings common to many of the tribes of the Central Asian steppes. Although it was taken "from life," the mask would probably have been preserved primarily as an artistic creation, rather than as a realistic facial imprint of the deceased.

Clay masks begin to appear in Yenisey burials after the end of the Hunno-Sarmatian period (second century BC to second century AD). They developed into a sophisticated artistic form in the later periods and became widely spread among the nomadic peoples of northern Asia and the Siberian forest steppes who practiced shamanism.

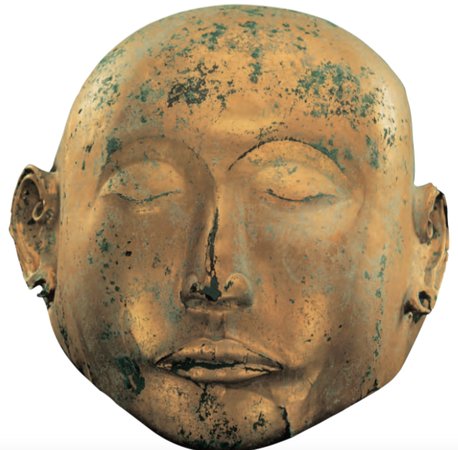

FUNERARY MASK

Khitan Culture, China

c. 1025

This gilt bronze funerary mask, found in 1986 in a burial in Qinglongshan Township, Naiman District, Inner Mongolia, was created in repoussé relief, the features hammered out from behind. The expression is serene, as if in sleep, or death. The arch of the nose is high and narrow, and the carefully sculpted ears are pierced for attaching the silk web that held the mask on to the back of the skull. The mask is thought to have belonged to a Khitan princess who died in the early part of the eleventh century; other artifacts recovered from the tomb include silver net clothing, a crown, gilt silver shoes and a belt.

The northern areas of China that now make up Inner Mongolia and the surrounding regions had their own distinct cultures, often independent of Chinese dynastic rule. The nomadic Khitan people were one such cultural group, whose powerful empire ruled an area of China north of the Great Wall, including modern Beijing and most of modern Inner Mongolia, from AD 916 to 1125. The Khitan artistic tradition was influenced by the forms, techniques and decoration of the Chinese Tang dynasty (AD 618–907).

TEZCATLIPOCA MASK

Mixtec Culture, Mexico

c. 1485

This striking mask is made from a halved human skull lined with leather. The front of the skull is covered with alternate bands of tiny turquoise and lignite mosaic that replicate the characteristic facial features of the Mexica (Aztec) deity Tezcatlipoca, a creator god associated with warriors, rulers and sorcerers. The inlaid eye orbits seemingly preclude this mask having been worn by the living, although the leather ties suggest that it was intended to be worn or hung in some way. Mexica tribute lists from the early sixteenth century note that each year the Mixtec of Oaxaca were required to supply the Mexica emperor Motecuhzoma II with ten turquoise mosaic masks made by skilled artisans. Only a few such masks have survived, and this is one of the finest examples, dating from between c.1450 and 1520.

The materials for the mask came from distant sources, their geographic origins indicating the extent of the economic networks and political power of the Mexica state. The turquoise came from northern Mexico or the American southwest, the shell originated in either the Pacific Ocean or the Gulf of Mexico, and the lignite was probably found in Guerrero, in southwest Mexico.

MAN-BEAR MASK

Tlingit / Haida Culture, USA

c. 1840

While totem poles are the most well known of Northwest Indian artifacts, dance masks display the greatest variety, vigor and aesthetic inventiveness. This remarkably expressive Alaskan mask was created using a wide variety of natural materials. The resplendent mother- of-pearl and metal inlay and the rare and costly blue-green pigment, obtained from copper-bearing clay, suggest that this mask was particularly highly prized. The mystical importance of the mask is made clear by the fact that the artisans who carved such sacred objects could not be watched at work, and a finished mask, imbued with spiritual power, could not be brought into the house.

This mask, dated to c.1800–1867, depicts a bear with human features. The tribes of the Northwest Coast believed that supernatural beings or spirits could only take animal form in the world of men. The bear was the lord of the forest, an emblematic animal that had lived in a mythical era, and as such one of the most revered shamanic beasts. A shaman probably wore the mask during the potlatch, a traditional festival of the Northwest Coast Indians held at times of transition such as births, deaths and marriages. During ritual ceremonies the shaman was transformed into the animal portrayed and took on the magical powers associated with it.

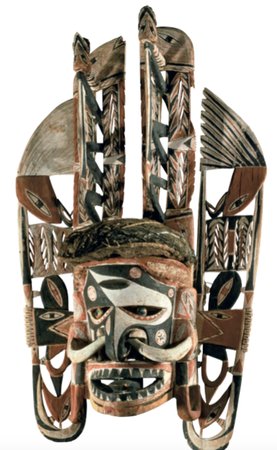

MALAGGAN MASK

Melanesian Culture, Papua New Guinea

c. 1875

Elaborately carved Melanesian masks such as this one, which bristles with animal imagery, represent wanis, or nature spirits. From New Ireland in Papua New Guinea, the face is essentially human, although boar tusks protrude from the nose. The dramatic earpieces include images of snakes and birds. The asymmetrical painting of the face enhances the mask’s wild appearance, and the overall impression is one of movement, transformation and ambiguity. No wonder the Surrealists were drawn to the art of New Ireland, for they saw in these works a connection to the visual puns and unconscious imagery that marked their own work.

The malaggan ceremonial cycle, a mortuary ritual that could take years to complete, included many dance performances; masks such as this sometimes appeared at the end of a ceremony, to suspend the social restrictions that had been in place during the funerary cycle. Unlike the carved figures that also featured, but which were sometimes discarded after the malaggan display, masks such as this one were meant to be worn repeatedly.

FANG NGIL MASK

Fang Culture, Equatorial Guinea

c. 1895

The immense looming presence of this nineteenth-century mask, with its massive domed forehead, was intended to intimidate as well as inspire awe. The apparition evoked is an immaterial one, apparent through its ghostly pallor, the wispy lines that minimally define the brows, and the radical tapering of the head. Its massive spectral manifestation was intended to suggest an abstract spiritual force rather than an overtly human subject.

The mask was worn in performances related to rites of ngi (ngil), a Fang anti-witchcraft association that transcended clan interests to regulate village life and protect individuals against mystical aggression. Ngi was credited with the ability to reveal hidden dangers, and villages adopted ngi ceremonies as they experienced a need to combat crises attributed to witchcraft by detecting and punishing sorcerers. Ngi members gathered in small groups with an emblematic mask, both to investigate foul play and to expose and bring the perpetrators to justice. The presence of the fearsome masked and armed representative served to enforce punishment of criminal behavior and pre-empt potential foul play.

BAULE TWIN MASK

Baule Culture, Ivory Coast

c. 1912

In Baule communities of West Africa, masks such as this are seen in performances of an operatic public entertainment known as Mblo, consisting of a series of skits that feature masked dancers who impersonate socially familiar subjects, ranging from animals to human caricatures. The succession of dances escalates in complexity and importance, culminating in performances that pay tribute to a community’s most admired member. A mask that is conceived as there artistic "double" or "namesake" depicts individuals honored in this way.

In the context of Mblo masquerades, a mask that generically refers to twins – who are credited with bringing fortune to their families and are considered to share a single soul – may appear midway through the sequence of social types portrayed, or at the culmination of the entertainment to honor specific individuals. This twin mask, dating from the late nineteenth century to the first half of the twentieth, displays distinctions that underscore contrasts between the paired faces: differences in scale, facial markings, coiffures, and colors, which refer to the essential dissimilarities exhibited by male and female twins.